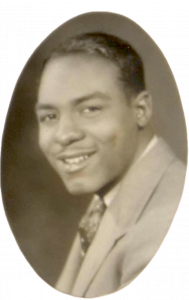

Photo info ...

Credit: Indianapolis Public LibraryView Source

(July 6, 1919-June 23, 1987). Andrew “Bo” Foster was born along an alley named Hudson near the apartment complex in Indianapolis. He grew up in the Colored Orphans Home at 25th Street and Keystone Avenue, attended (IPS) No. 37, and graduated from in 1938.

During World War II, Foster graduated from officer candidate school at Camp Hood, Texas, as a lieutenant and served on a tank destroyer unit. After his service, he returned to Indianapolis where he worked as a janitor at two local plants and as a trashman. Foster saved enough money to purchase a secondhand truck to begin hauling trash on his own. He used the profits from this business to buy a private rooming house as another source of income. Foster’s work ethic and vision helped lead to the establishment of a successful Indianapolis trucking company, and subsequently, an even more profitable business in motels to serve the Black community living in and traveling to segregated Indianapolis.

At a time when Black Americans were turned away from hotels, Foster’s businesses were one of the only ones in Indianapolis to accommodate them. In 1948 Foster built an 11-room motel at the corner of 2100 N. Illinois Street in downtown Indianapolis. The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, which listed safe and welcoming businesses and accommodations across the country, included both Foster Hotel and the Guest House from 1955 to 1977. These facilities served tourists and famed guests, such as Muhammad Ali, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton (see ), Nat King Cole, and Ray Charles. Foster went on to open the Foster Manor House Motel, the Carrollton Hotel, and many private rooming houses. Patrons praised all the facilities for their cleanliness, modern features, and hospitable staff.

In addition to financial success, Foster founded his businesses to meet the need for a communal space in which to socialize, politically organize, and participate in civic and philanthropic events. According to the , Foster “saw blacks holding meetings at white-owned establishments ‘where they couldn’t always speak their peace’” and sought to provide a venue where they could.

Foster opened Pearl’s Lounge to provide such a space in 1970. Named for his wife, the cocktail lounge opened at 118 West McLean Place. The venue’s banquet hall and ballroom facilitated numerous events, including a meeting of Black IPS teachers, a fashion show, NAACP events, a voter registration program, and an Indiana University alumni meeting about how to serve Black students. The Recorder reported in 1975, “In their first major attempt to acquaint the owners, coaches, and players with the black community, the will host a reception and a buffet dinner” at Pearl’s. The lounge also hosted numerous political campaign events and debates—including those of Mayor , Rev. , Senator , and Senator —in addition to hosting the Indiana Conference on Black Politics, Indiana Black Republican Council meetings, and a Socialist Workers Party rally.

Foster not only uplifted the community through his businesses but as president of the Indianapolis chapter of the National Business League (NBL) in the 1960s and 70s. Through the NBL—described as the “chamber of commerce of Negro enterprise”—Foster mentored Black business owners, helped them obtain grants, and matched minority-owned businesses with “established corporate buyers.” Under his leadership, the NBL worked with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket to offer entrepreneurs seminars about topics like accounting trends and business law. In an article, Foster described the impetus for his work with the NBL, stating “’Let’s face it, the economic success of Negro businessmen means more jobs for Negroes, more property, more education, better skilled professionals and a better community.’” Foster also lent his expertise to the co-founding of the Midwest National Bank in 1972, which publicly objected to redlining practices, issued “inner-city” loans, and appointed women to several leadership positions.

In 1982, Governor Robert Orr awarded Foster the prestigious Sagamore of the Wabash in recognition of his civic contributions. Reflecting on his prolific career, Foster told the Recorder in 1983 that he had no formal training, “just high school, the Army and common sense. I came out of the Army and started hauling trash. I saw a need for a black hotel, then added a motel three years later in order to survive.” Foster passed away five years later, having increased capital and equity for Indianapolis’s Black community.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.