A city located 38 miles northeast of Indianapolis on former Delaware Indian land, Anderson is the county seat of , which is included in the Indianapolis . The city was founded in 1823 at the site of a Delaware Indian village. Modern-day Anderson derived its name from sub-chief, William Anderson, also known as Kikthawenund, whose mother was a Delaware (Lenape) Indian.

Original settlers to the area referred to the village as Anderson Town, though nearby Moravian Missionaries called it “The Heathen Town Four Miles Away.” Later the village was known as Andersontown, and in 1844 the Indiana General Assembly shortened the name to Anderson.

, an early settler of the land, was the first to influence the history of the village when he sold his property to John and Sarah Berry. The Berry’s donated 32 acres of their land to Madison County with the stipulation that Anderson would become the county seat. County officials agreed, and on November 7, 1827, John Berry finished his survey and platted out the original layout for Anderson. The county seat was moved from its existing place in Pendleton to Anderson alongside the exchange of land ownership about one year later.

In 1837, plans to introduce the through the middle of Anderson promised growth and internal development, which facilitated Anderson’s incorporation as a town in December 1838 with a population of only 350. When those plans did not materialize, Anderson experienced an economic downturn and lost its status as a town.

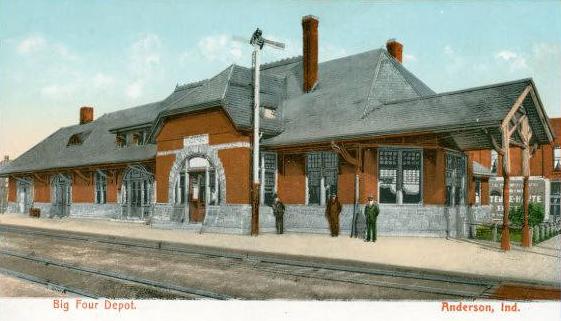

More than a decade later, in 1849, Anderson attracted commercial venues and reincorporated as a town. It lost this status again in 1852. However, that same year the new Indianapolis-Bellefontaine Railroad and its station in Anderson revitalized the village, which allowed Anderson to incorporate as a town for the third and final time on June 9, 1853. As the town’s population grew the town incorporated as a city on August 28, 1865, with a population of 1,300.

Between 1853 and the late 1800s, 20 industries located at Anderson. On March 31, 1887, the discovery of natural gas further spurred industrial growth, bringing with it job opportunities and a population explosion. The city’s accelerated growth earned it nicknames such as “Pittsburgh on the White River” and “Queen City of the Gas Belt.”

The city, however, received yet another major setback with the depletion of natural gas in 1912. Many industries left Anderson but the Commercial Club, the forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce that formed on November 18, 1905, persuaded a handful of businesses to stay in Anderson.

At the same time, the Church of God Ministries established its headquarters in Anderson in 1904. (The denomination stems from the Holiness tradition. Most scholars append Anderson to distinguish it from other Church of God denominations with which it does not share Pentecostal practices.) Shortly thereafter, in 1917, the Anderson Bible School and Seminary was founded, later named Anderson College in 1925, and finally Anderson University in 1988.

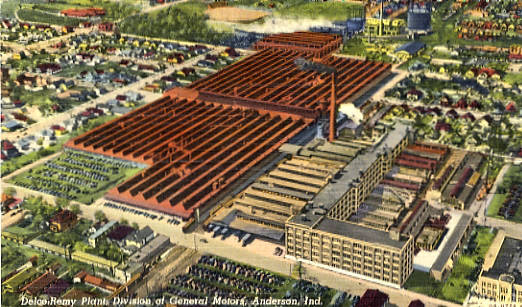

Despite the economic setback experienced in the first decade of the 1900s, Anderson soon became defined by its association with the auto industry. Auto industry-related businesses that manufactured transmissions, generators, gears, and headlights found their way to Anderson. The Guide Motor Lamp Company of Cleveland, Ohio became a part of General Motors’ (GM) Delco-Remy Division in Anderson by 1928.

Anderson became a bustling auto town in the 1930s with roughly 8,000 employees scattered across seven GM plants. It was during this decade that the United Auto Workers (UAW) organized to represent auto workers’ rights. They targeted Anderson’s GM divisions of Delco Remy and Guide Motor Lamp, which resulted in those pro-union workers initially staging a sit-down strike on December 31, 1936, and eventually vacating the plants on January 16, 1937. One hundred sixty-nine workers remained in the plants for 18 days.

GM finally recognized the union despite agitation by anti-unionists on January 25, 1937. Less than two days after union recognition, Indiana governor Maurice Clifford Townsend implemented martial law in Anderson after a union-related riot ensued at a local tavern on February 13, 1937. The Indiana State Police and 1,000 National Guardsmen held vigil over Anderson until February 23, 1937, when tensions between pro-union and anti-union activists calmed. The UAW Local 662 received its charter in May 1939 and began representing the rights of the unionized auto workers of Anderson.

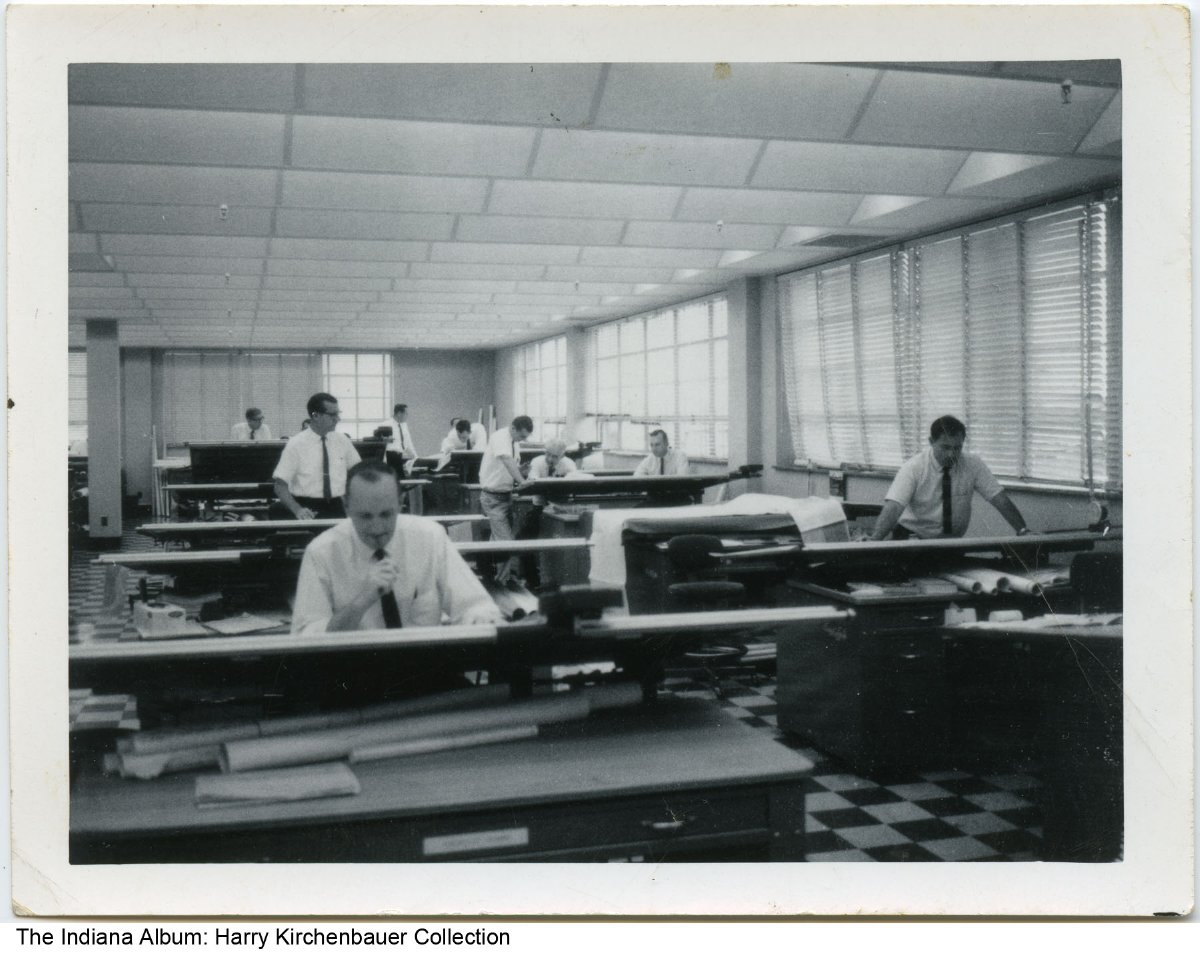

Anderson’s GM divisions prospered for almost 70 years after the tumultuous labor events of late 1936 and early 1937. During the 1940s, Delco Remy doubled its workforce, tripled production, and opened two more plants, while the labor union successfully bargained for increased employee wages. Though the union sold four properties in 1953, it built a 46,000-square-foot union hall that stood as a visible sign of the union’s power.

Part of that power was reflected in the improvement of the community at large, not just the lives of the workers. Local 662 secured higher wages, stable working hours, safe working conditions, and health and pension benefits for GM employees, but it also helped GM families secure housing loans, find childcare and acquire education through General Education Degree (GED) programs and flexible work hours to accommodate attendance at local colleges.

Anderson prospered during the 1960s and 1970s as a result of GM controlling 40 percent of the auto market. By 1974, Anderson’s 20 GM plants claimed 25,000 workers under their roofs. Yet foreign competition and the movement of manufacturing to Mexico, China, India, and Brazil led to layoffs during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1998, GM spun off Fisher Guide, the result of a 1984 merger between Guide Motor Lamp and Fisher Body Division, as Guide Corporation an independent company that manufactured headlights solely for GM. With GM’s dominance in the auto industry waning, the potential and the possibility to compete in the global market grew dimmer. Guide Corporation decided to wind down and shutter operations in 2007.

Anderson has sought to diversify its economy through the recruitment of the healthcare industry and as a distribution center for various industries. More than a dozen of the former GM plants have been torn down and the land underneath them cleaned up for new development. Anderson’s top five employers are Community Hospital Anderson, Saint Vincent Anderson Regional Hospital, Nestle, Hoosier Park Racing and Casino, and Carter Express. The city has been recognized for its creation of a workable blueprint other communities can use when manufacturing leaves an area.

The city government consists of an elected mayor and city council which represents four townships. The Anderson Community School Corporation includes one consolidated high school, one junior high school, six elementary schools, a kindergarten center, and a preschool. Anderson has one charter school and several parochial schools. Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana is located in the city, as is Anderson University, a private Christian college associated with the Church of God (Anderson).

A major point of interest is Mounds State Park located east of Anderson. Its 10 unique ceremonial earthworks were built by the prehistoric Adena indigenous peoples of eastern North America and used centuries later by Hopewell culture inhabitants. The largest earthwork, the Great Mound, is believed to have been constructed ca. 160 B.C.

FURTHER READING

- Anderson, IN. “History.” https://www.cityofanderson.com/209/History.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Verderame, J. A. (2021). Anderson. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 4, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/anderson/.

MLA:

Verderame, Jyoti A. “Anderson.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/anderson/. Accessed 4 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Verderame, Jyoti A. “Anderson.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Mar 4, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/anderson/.

Is this your community?

Do you have photos or stories?

Contribute to this page by emailing us your suggestions.