Americanization programs were aimed at socializing immigrants and their children to the norms of middle-class, native-born Americans. That Americanization was one of the early purposes of free, public education can be seen by Indiana’s School Law of 1855, which required that the common schools be taught in the English language, a requirement reiterated in the School Law of 1865. At the time of the first law, the non-native population of Indianapolis was composed primarily of Germans, who numbered close to 4,000; as of 1869, however, only 34 German-born children were enrolled in Indianapolis public schools.

Those who supported the teaching of German in public schools argued that instruction in their native language would hasten the Americanization of German-speaking students and entice more German parents to enroll their children in public schools. By the early 1880s, Indianapolis offered a dual language (German-English) program aimed at both native-English and German-speaking pupils. This unique program was one of the earliest to promote assimilation through bilingual education. But German immigration virtually ended in the 1890s, and, in response to World War I, the teaching of German in common schools was banned by 1917.

In 1915, Indianapolis’ immigrant population, largely eastern and southern Europeans, was estimated at 14,000, under 10 percent of the total population. Manual High School and Public School 5 offered night classes to “foreigners.” Courses included beginning English, citizenship preparation, and vocational classes. Enrollment at these two centers totaled 269, but other agencies also conducted Americanization classes for immigrants.

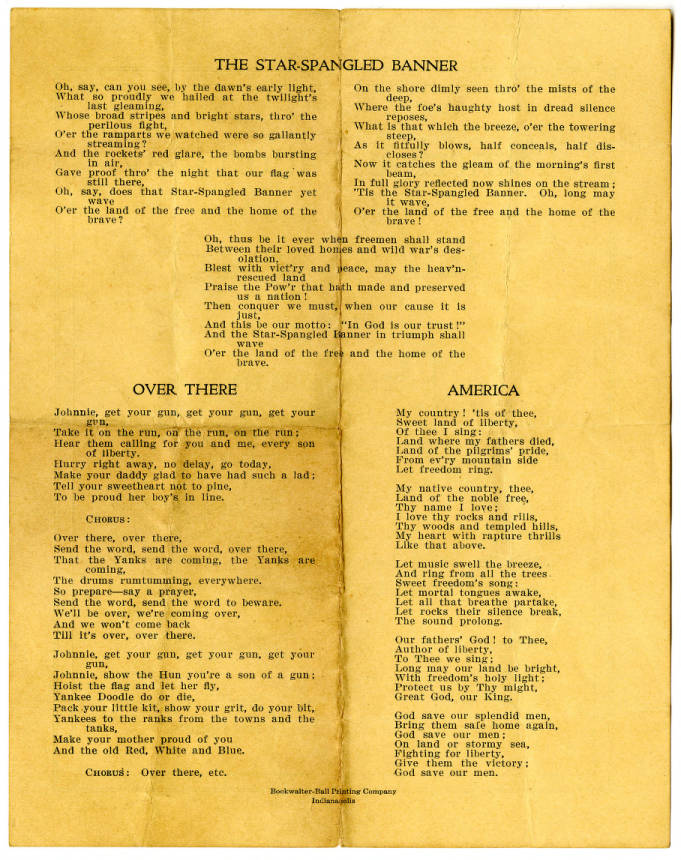

Pre-World War I Americanization programs focused primarily on teaching English, plus social and vocational skills. After the war, Americanization acquired a more nationalistic tone. Teachers were pressured to incorporate into the curriculum Americanization lessons stressing the importance of citizenship, democracy, and patriotism. Indiana University Extension Division offered classes and institutes to train teachers to teach Americanization. The State Board of Education proclaimed October 24, 1919, “Americanization Day” and urged all public schools to celebrate with programs of patriotic songs and readings.

In 1926, the Director of Naturalization for Indianapolis recommended that the public schools organize an evening citizenship class for adults. The first class was held October 16, 1926, at Manual High School. Taught by a history teacher at the high school, the course consisted of 30 two-hour lessons in United States history and government. Ability to speak and write English was a prerequisite. Enrollment in the first three sessions totaled 185. Soon all other agencies discontinued their classes and urged attendance at this centralized location.

By the 1930s, the number of immigrants in Indianapolis, and their percentage of the city’s population, had declined. In 1933, 9 out of 10 students enrolled in night schools were American-born. Concern with immigrant socialization waned in the face of this demographic reality.

The arrival of large numbers of Latinos in recent decades has once again raised complaints, usually focused on bilingual signage. The increasingly strong economic connections between Indianapolis and world trade, however, have proved a countervailing force, with schools offering instruction in a variety of languages that are viewed as an aid to commerce.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.