Because of the harsh remedies of bloodletting and purging employed during the early 19th century, many Indianapolis residents avoided physicians altogether. Home remedies passed down through the generations provided treatment for these people and also for those who could not afford medical fees or lived too far from a physician. Roots, herbs, and materials from surrounding forests and kitchen gardens were used to heal the sick or injured. Some settlers also employed Native American medical therapies.

Self-treatment was popular during the Jacksonian era. Indianapolis residents may have used home remedy books like Dr. C. Vanhook’s (1832) published in Vincennes, Indiana. Samuel Thomson’s (1767-1843) also offered self-help to an estimated one of every six Americans in the 1830s.

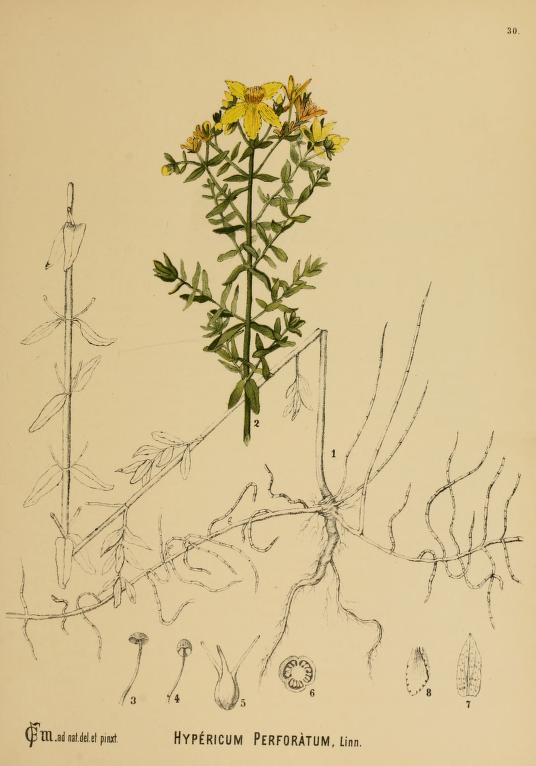

Thomson’s botanical system of medical treatment featured use of steam baths and herbal medicines to restore the patient’s loss of body heat, which he thought to be the cause of disease. Dr. Abner Pope, who came to Indianapolis in 1836, sold Thomsonian products like lobelia inflata, cayenne pepper, prickly ash, and other botanicals at Pope’s Drug Store. He prescribed steam baths and encouraged the formation of Thomsonian “Friendly Botanic Societies” to promote Thomson’s course of treatments.

By adopting some of the practices of traditional medicine that were successful in treating disease, the Thomsonians spawned two sects that gained adherents in Indianapolis and elsewhere. The Eclectics used methods of medical treatment from any source if it was effective and the PhysioMedicals used highly concentrated doses of botanic medicine in treating illness.

Both shunned mineral-based medicines, use of toxic materials, and bloodletting. However, they agreed that formal medical education was desirable. Both groups published medical journals and formed medical societies in Indiana and had practitioners in Indianapolis. The Eclectic Medical Association was organized in Indianapolis in 1857. In 1878 it began the and three years later established a medical college at Indiana Avenue and California Street. The Physio-Medicals convened in 1874 and decided to publish the . The editor, Dr. George Hasty, was the founder of the Physio-Medical College in Indianapolis.

One of the first physicians to practice medicine in pioneer Indianapolis was Dr. . He was a traditional practitioner who converted to the practice of homeopathy later in his career. Homeopathy promoted exceedingly small doses of medicine prescribed on the “like cures like” principle. Medicines consisted of botanical substances instead of minerals, narcotics, or alcohol. Coe introduced Indianapolis to cinchona bark, the source of quinine, for treatment of the malarial fevers rampant in the community.

Since epidemics were frequent and fevers always a menace, homeopathy offered a safer way to treat contagious illnesses than the allopathic methods of harsh chemicals and bloodletting. In an attempt to stop homeopaths from legally practicing medicine, regular physicians refused homeopaths hospital privileges. Not until the 20th century did local Indianapolis homeopathic physicians gain hospital privileges, and then these privileges were only available at .

Despite regular medicine’s attempt to limit homeopathy, it remained the second most popular form of medical care into the 20th century with its own medical schools and medical societies. The Indiana Institute of Homeopathy was formed in 1867 while the Marion County Homeopathic Society was organized in 1871. Both were located in Indianapolis.

The prevalence of endemic and contagious diseases in the Indianapolis area provided a climate for the sale of over-the-counter patent medicines advertised as cure-alls. These products were available and popular in the city from its earliest days until the advent of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938.

Promoting the control of patent medicines proved easier than control of osteopathy and chiropractic medical treatments, practices opposed by regular physicians and the American Medical Association. Chiropractic and osteopathic medical treatments depend upon manual manipulation of the muscles, tissue, and bones of patients by their practitioners.

Chiropractic treatment was based on the theory that the misalignment of the nervous system caused disease. Realignment by chiropractic manipulation of the vertebrae was the prescribed cure. By 1906 a school had been established in Davenport, Iowa, for chiropractic training. Chiropractors first appeared in Indianapolis soon afterward and by the mid-20th century chiropractic treatment was widely available to local residents. Although orthodox medicine also branded it a quack cure, chiropractic medicine today is well established.

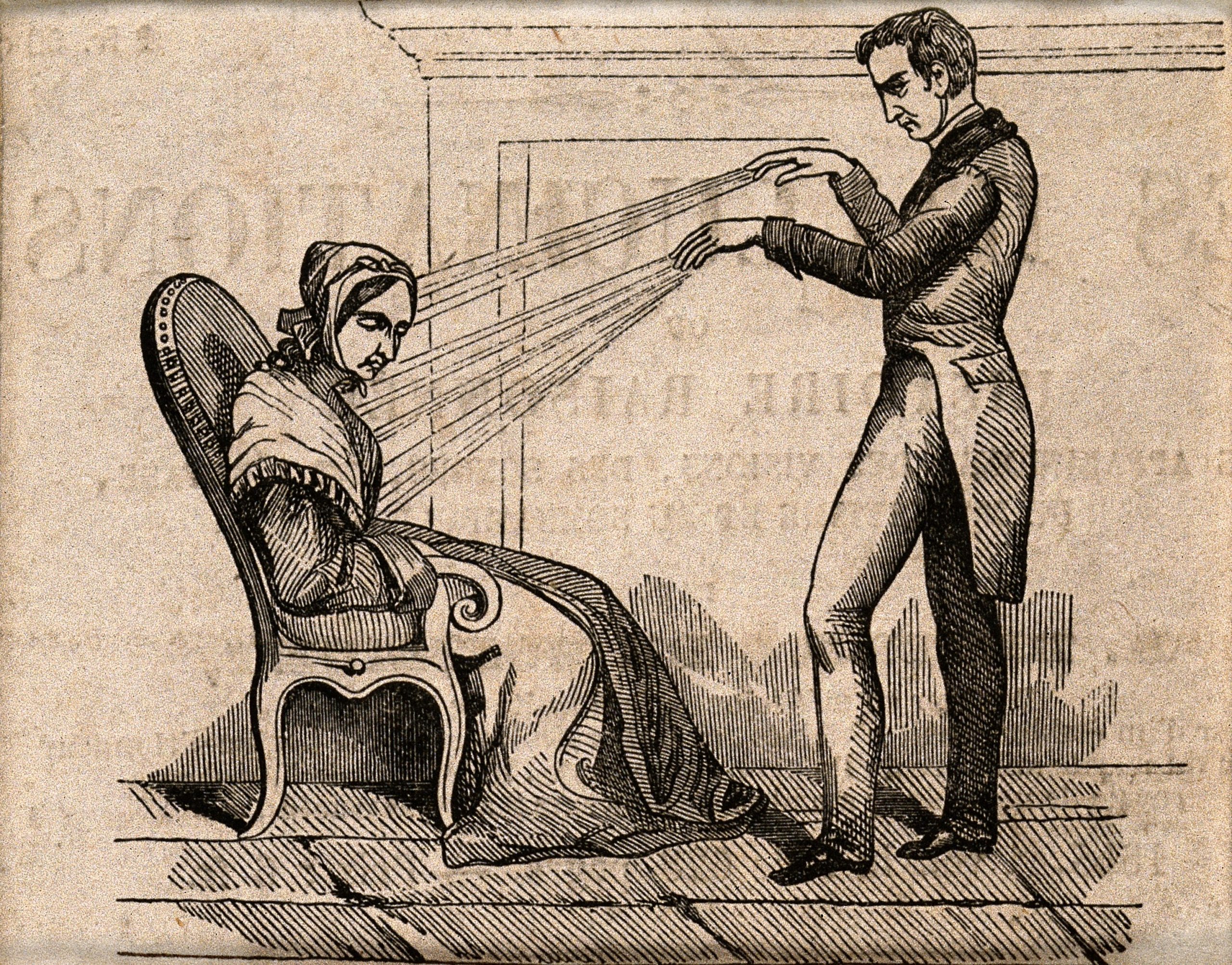

Other nontraditional healthcare systems that claimed to cure disease also made their appearances in Indianapolis. Mesmerism was based on the notion that disease stemmed from an imbalance of an invisible electrical magnetic fluid in the patients’ bodies. Mesmerists gained considerable popularity in the 19th century and expanded their following in the 20th century when various electrical devices like the Radioclast and the Master Violet Ray Kit were used to treat patients.

These devices eventually became illegal when their effectiveness and safety could not be demonstrated to the scientific community. The followers of Mesmer in Indianapolis in the 1840s gave lectures and demonstrations of cures for illnesses by the use of magnetized rods. The subjects responded to the ritualistic method of mesmerism by becoming hypnotized. Elaborate claims of cures for disease were attributed to this hypnotherapy along with other cures that seemed to hold promise.

By the late 19th century, hydropathy, or water-cure therapy, increased in use as an alternative to the bloodletting of the conventional physicians in Europe and the United States. Water cures originally consisted of wrapping patients in wet sheets. Practitioners also promoted treatment such as imbibing pure water as well as mineral water and applying water externally through ice pack treatment, wet pack treatment, steam bath treatment, and sitz baths. Late in the century, Indianapolis residents could take the waters at Mudlavia in Warren County, French Lick, West Baden, or Trinity Springs in Martin County, and numerous other spas throughout the state.

Adherents drank both pure and mineral bottled water. Bottled water offered a safer source of drinking water than the public water supply until the succeeded in offering safer drinking water around the turn of the century. In 1899 the Mount Jackson Sanitarium opened in Indianapolis on West Washington Street. The owners claimed that the mineral well located there could cure rheumatism, dyspepsia, and nervous prostration, as well as liver, blood, skin, and stomach troubles.

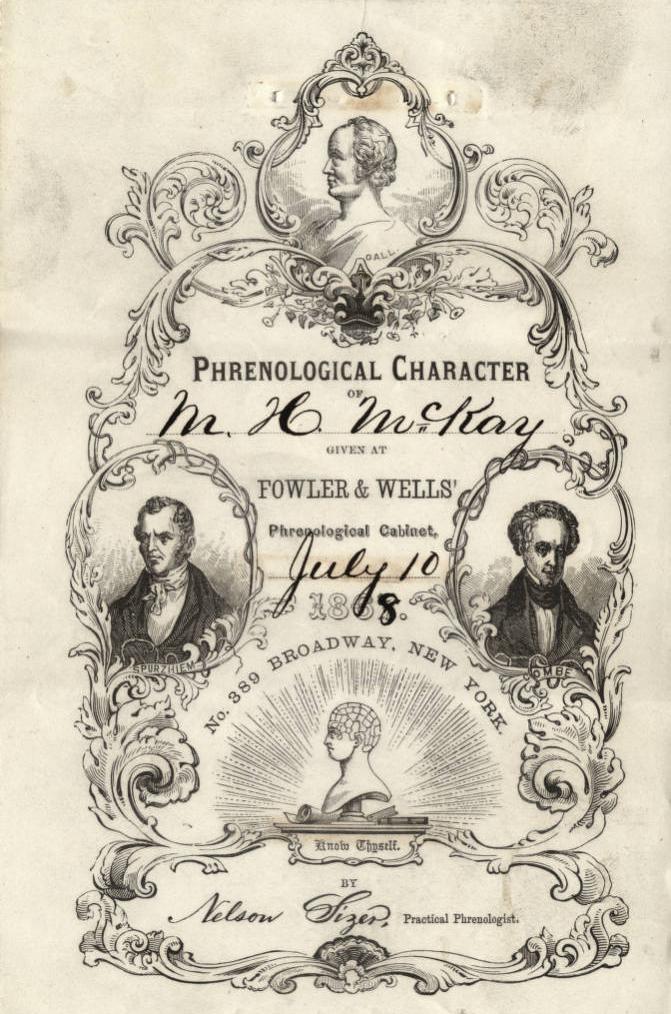

Phrenology was another alternative medical practice available in 19th-century Indianapolis. This movement postulated that a direct relationship existed between personality and the shape and size of the brain. , the prominent Indianapolis pioneer and attorney, was familiar with the ideas of phrenology. He and his family and friends attended numerous lectures by phrenologists who traveled to Indianapolis to analyze the heads of local citizens. , minister at , was an early convert to phrenology through Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, founders of the movement. (Orson Fowler was Beecher’s classmate at Amherst College.)

Two significant religious movements claimed to be able to cure disease if members followed their belief systems. By the 1880s, Mary Baker Eddy formalized as Christian Science her metaphysical healing by the “Divine Mind” cure for disease. The first listing for Christian Science practitioners in Indianapolis city directories appeared in 1911. Women were trained as practitioners, and many women’s names appear in Polk’s directory through subsequent editions.

Another religious healing movement that attracted adherents in Indianapolis was Seventh-Day Adventism, which established a church in 1863. Founder Ellen G. White’s program of healing required to abstain from meat, tobacco, alcohol, and drugs, and from all but minimal sexual activity. White wrote books about her religious health reform principles, lectured on the American temperance circuit, and established health retreats and hospitals in the United States and beyond.

Osteopathists, who counted African Americans and women in their ranks, first appeared in the Indianapolis city directory in 1904, with eight listings including the Spaunhurst Institute of Osteopathy in the State Life Building. Although the American Medical Association fought hard to eliminate the legal practice of osteopathy from its inception, the practitioners eventually accepted the system of regular medicine and added it to their educational requirements.

Since 1973, doctors of osteopathic medicine (D.O.’s) have been fully recognized as medical doctors in all 50 states. D.O.s have hospital privileges and practice alongside traditional doctors of medicine (M.D’s). They prescribe medications and perform surgery, unlike chiropractics.

, the first osteopathic hospital in Indianapolis, opened in 1975. It became part of the Community Health Network in 2011. In 2013, Marian University founded its College of Osteopathic Medicine (MU-COM). From the closing of the last proprietary medical schools at the beginning of the 20th century until this time, (IUSM), the traditional allopathic, or traditional, medical school, had been the only existing medical school in the state. The first class of the College of Osteopathic Medicine included 162 students and began taking classes in August 2013. Accredited by the American Osteopathic Commission on Osteopathic Accreditation, graduates of the school receive the Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.).

Westview Hospital seemed the perfect place to establish MU-COM’s physician education programs, and Community Health Network partnered with MU-COM to put such a program into place. By 2015, however, only one MU-COM student a month shadowed Westview osteopathic physicians. Reflecting a growing acceptance of osteopathic medicine and its increased integration into traditional hospitals, Westview did not survive. The Community Hospital Network stopped providing inpatient care at Westview in 2015 and vacated the building when it closed its emergency department at the end of 2016. MU-COM physician education continued at other Indianapolis sites in the Community Health Network, the St. Vincent Health Network, , and the Methodist Hospital Sports Medicine group.

Mutual skepticism has characterized the relationship between conventional medicine and alternative healthcare theories from the early days of settlement in Indianapolis to the present. Despite the vast improvement of conventional medicine, alternative healthcare treatment is still popular. Major Indianapolis bookstores have special sections to sell alternative healthcare information alongside information on traditional healthcare, and city directories list a wide range of alternative healthcare providers.

In 2018, Indiana legalized cannabidiol (CBD), derived from the cannabis or marijuana plant, and it became popular as a natural remedy used for many common ailments. Unlike tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) CBD is not psychoactive. Believed to alleviate pain, anxiety and depression, cancer-related symptoms, acne, and other disorders, CBD oil has been characterized as a sort of cure-all medication, similar to some 19th-century home remedies. Further research is needed to prove or disprove these claims.

FURTHER READING

- McDonell, Katherine Mandusic. Medicine in Antebellum Indiana: Conflict, Conservatism and Change. Indiana Historical Society, 1984, https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/10587670.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Blunk, A. & Van Allen, E. J. (2021). Alternative Medicine. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 20, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/alternative-medicine/.

MLA:

Blunk, Ann and Elizabeth J. Van Allen. “Alternative Medicine.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/alternative-medicine/. Accessed 20 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Blunk, Ann and Elizabeth J. Van Allen. “Alternative Medicine.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Feb 20, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/alternative-medicine/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.