African Americans have had a significant presence in Indianapolis news reporting for more than a century in print, broadcast, and digital media.

Newspapers and Print Media

African American involvement in media can be traced to 19th-century newspapers, the city’s earliest form of news reporting.

By the late 1800s, newspapers were the dominant form of media, but racial segregation prevented most Black writers, editors, and printers from working at white-owned publications. In response, African American publishers started their own newspapers in Indianapolis to accommodate the rapidly growing Black population.

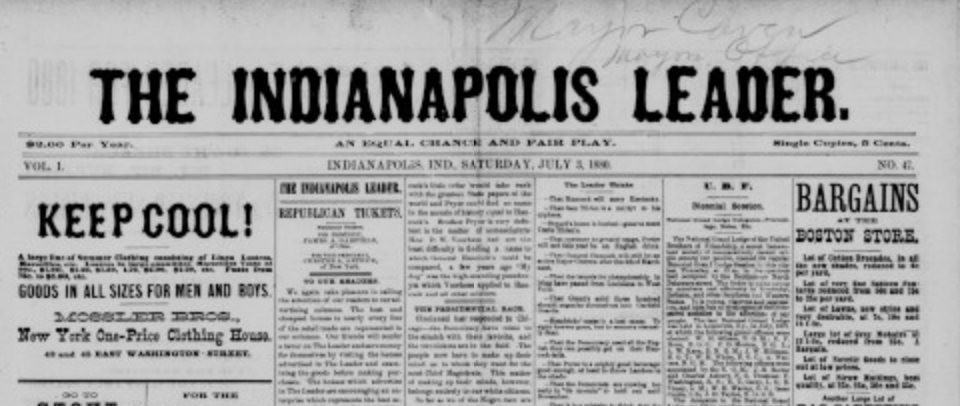

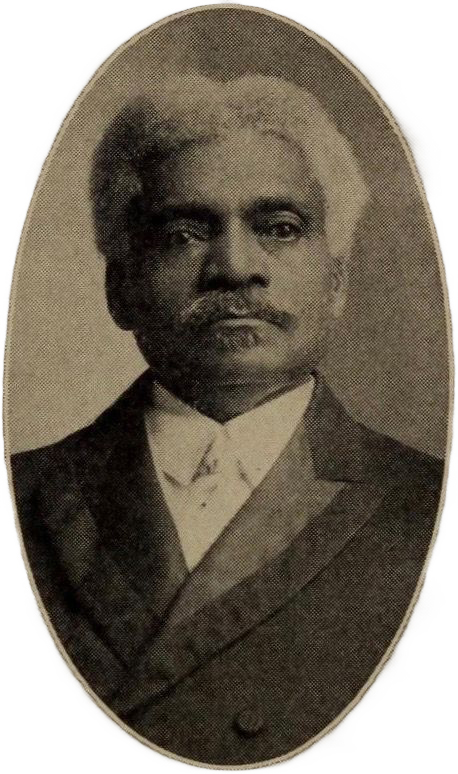

In 1879, the was launched as the city’s first African American-owned newspaper. It was published by and his brothers Benjamin and James, former slaves who all became prominent educators. Operating with the motto “An Equal Chance and Fair Play,” the newspaper strongly called for elevation of the “colored” race.

It reported society news for African Americans and encouraged southern African Americans to migrate north for greater freedom and economic opportunities.

Due to the Bagby’s connections with the state’s powerful , the thrived. However, the Bagbys sold it in 1885, and Robert Bagby went on to become the first African American elected to the Indianapolis City Council.

Other local Black newspapers soon emerged, including the , launched in 1883. In 1888, the was established by Edward Elder Cooper and became the first illustrated African American newspaper in the United States. Circulated nationally, the featured articles by Richard W. Thompson, who became managing editor and was recognized as one of the best newspaper correspondents in “the colored press.” The paper focused on the actions of past Black figures who were illustrated on the front pages. Political cartoons and photographs appeared in later years.

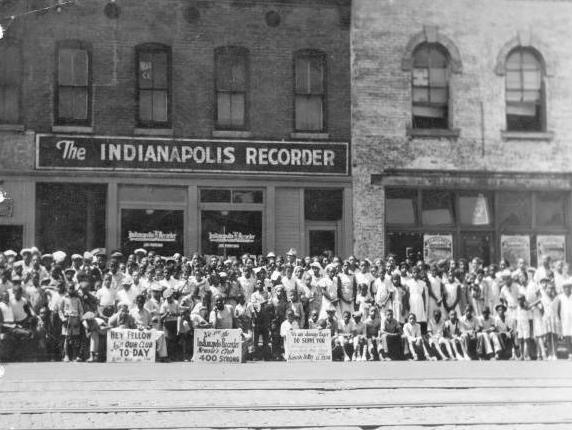

In 1895, the newspaper started as a two-page church directory by print shop owner George P. Stewart and attorney William Porter. While the city’s other Black newspapers were known nationally, the set itself apart by also focusing on local news. Coverage included church news, announcements, and other topics of interest to Black churches, fraternities, sororities, and social clubs.

, a writer for the , was the first African American woman to appear as a columnist in Indianapolis. In 1900, she joined , one of the city’s major daily newspapers, becoming the first Black columnist to be featured in a local newspaper that was not Black owned.

Between 1900 and 1925, Black publishers such as the ’s Stewart, of the and Levi Christy of the used their newspapers to promote racial equality, support Black businesses, and encourage readers to support political candidates who opposed the . However, by the 1920s, the secured its place as the city’s dominant African American media publication. Publisher George P. Stewart died in 1924. He was succeeded as publisher and owner by his wife Fannie Caldwell Stewart and as managing editor by their son Marcus C. Stewart.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, African American newspapers provided helpful information during the Great Depression and covered Black contributions to the Allied war effort during World War II.

New African American publications emerged during the 1950s as the civil rights movement expanded into cities across the country. After working as a writer for the Opal Tandy gained control of the newspaper in 1959 and changed its name to .

During the 1960s, both and contributed to the civil rights movement by advocating for legislation to end racial discrimination in employment, education, housing, and public accommodations.

By the 1970s and 1980s, held personal significance for families who participated in numerous community events sponsored by the newspaper. Recorder columnists such as spoke boldly and eloquently for racial justice and economic equality. Others like William “Skinny” Alexander and Virginia Kersey provided entertaining coverage of social events and church activities. William Raspberry, who began his journalism career at the , went on to work for the , where he became a nationally syndicated columnist and Pulitzer Prize winner.

Marcus Stewart and Opal Tandy both died in 1983, but continued to operate under the leadership of Tandy’s wife, Mary B. Tandy, who became one of the few African American women to publish a newspaper. She was joined in this distinction by Eunice Trotter, a career journalist who purchased the controlling interest of from the Stewart family in 1988.

After briefly updating the newspaper, Trotter sold to , an influential business owner and civic leader in 1990. As publisher, Mays increased circulation and advertising revenue. In 1995, ’s highly anticipated Just Tellin’ It column became a very popular feature of the newspaper.

In 1998, May’s niece, Carolene Mays-Medley, became ’s new president and general manager. Under her leadership, the publication returned to financial solvency and built a new team of experienced editors, reporters, and graphic designers who enhanced for the 21st century.

Local magazines also featured Black journalists and news of interest to African Americans. , the city’s largest African American congregation, published , which set a national standard for reporting church events and community news. By 2000, managing editor Debra Marshall expanded it from a newsletter to a monthly magazine with a committee of writers and photographers. had thousands of readers, with large churches as far away as Baltimore and Dallas using it as a template for their magazines.

After 2000, other prominent publications such as and Newsweekly increased their involvement with Black writers and columnists. Shari Finnell became editor-in-chief of the monthly magazine following a successful career as a reporter with the United Press International (UPI), the , and the .

African American reporters also developed a stronger presence at the Indianapolis Star, the city’s daily newspaper. James Patterson, Lynn Ford, Erika Smith, and Rishawn Biddle were columnists who added a more diverse voice to the and brought attention to critical issues facing the city at large. Jacqueline Thomas joined the in 2004 and became senior editor. She managed its features sections, regional magazines, and the young adult weekly publication . In 2020, Katrice Hardy became the first African American and first woman to head the Star as executive editor, leading the paper to a Pulitzer Prize in 2021 for national reporting before leaving to become editor of the Dallas Morning News.

In 2003, was launched by Indianapolis radio personality Rickie Clark to highlight successful minority business owners and professionals across the state. In 2007, the magazine was acquired by , which expanded it into a quarterly publication focused on business, lifestyle, and diversity news.

With Shannon Williams as president and general manager from 2010 to 2018, adjusted to the new digital age of media. It overcame many of the challenges that forced other newspapers to go totally online or shut down. increased efforts to attract younger readers with the use of electronic media such as its website and social media platforms.

Despite the greater consumer demand for digital media, Cliff Robinson’s continued to grow as a monthly print magazine. Robinson founded the popular source for African American entertainment and new businesses in the Indianapolis area in 1997. Throughout the 2010s and 2020s its popularity remained strong. Robinson also embraced technology through a digital format of the print magazine, a Facebook page, a Twitter account, and a weekly podcast where he introduced listeners to industry experts who share their business expertise.

Television Media

African Americans rarely appeared on television when it emerged during the late 1940s. However, a small number of Black professionals worked behind the scenes among the production crews of Indiana’s first television stations.

In 1949, Charles Haines joined as an advertising artist. He was the first African American hired full-time at a local television station. Haines became chief artist at WLWI-TV (later ) in 1957 and worked there until his retirement in 2006.

Steve Scott was the first African American executive of an Indianapolis television station. He was director of state license renewal and public affairs for WFMB television and radio. In 1969, Scott became the first African American in broadcasting to receive the prestigious Casper Award from the . It was presented for his work in hosting the television program Job Line.

Scott achieved many firsts in local media as a person of color. He was the first Black graduate of Indiana University’s department of radio and television broadcasting. He also became the first African American elected to the board of directors of the Indiana Broadcasters Association.

In 1969, Barbara Boyd joined WFMB-TV (later ) as a consumer reporter. She became the first African American woman to anchor a news show in Indianapolis. Boyd’s segments about economic and social issues quickly gained a following among viewers. She won numerous awards and was named Woman of the Year by the American Cancer Society after reporting on her own mastectomy from a hospital bed. Boyd remained with WRTV until her retirement in 1994. In February 2021 she cohosted a throwback telethon on WRTV and wrtv.com to benefit the United Negro College Fund just as she had done decades before.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, other local stations gradually added African Americans to their staff. Janet Langhart went on the air as host of ’s Indy Today in 1972. She was the first African American and one of the first women to host a daily talk/interview show in Indianapolis. In 1973, after Langhart left to join a station in Boston, prominent African American personality and entrepreneur Alpha Blackburn took over as host of Indy Today.

In 1979, Derrik Thomas became a reporter with WRTV-TV 6. He enjoyed an illustrious 40-year career with the station that earned him numerous awards from organizations such as United Press International, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Associated Press. He was ranked as a top reporter in several independent polls of Indianapolis viewers. Tina Cosby moved to Indianapolis in 1983 to work for WISH-TV 8 as a reporter and anchor. She was also host and producer of Black Focus, a public affairs talk show. Cosby returned to WISH-TV 8 as community affairs director in 2002.

In 1986, Lis Daily joined WISH-TV 8 as an anchor and reporter. However, her best-known television contributions came in 1995, when she became community affairs director for WTHR-TV 13. Daily was host of the station’s community calendar segments. She launched the 13 Listens outreach program and bus tours and attended dozens of community meetings. She helped coordinate the Children’s Miracle Network Telethon to benefit and worked with the United Negro College Fund telethon. Dailey remained with WTHR-TV 13 until her death from cancer in 2002.

Also in 1986, Angela Cain began her long media career by joining WRTV-TV 13. After briefly working for a station in Dallas, Cain later returned to Indianapolis to succeed Lis Dailey as community affairs director for WTHR. She oversaw many community projects, including Coats for Kids, the United Christmas Service Campaign, and Shattering the Silence, an award-winning campaign to prevent domestic abuse. She also hosted WTHR’s “Community Calendar and Focus” segments on Eyewitness News at Noon.

By the early 1990s, the Indianapolis affiliates of major networks ABC, CBS, NBC, and FOX all had at least one African American featured on daily newscasts. In 1991, Chris Wright made his television debut as a meteorologist with the new . He was later the primary meteorologist with WISH-TV 8 and joined WTHR-13’s SkyTrak Weather team in 1999. Sandra Chapman began her tenure as an investigative reporter and weekend anchor for WISH-TV 8 in 1993. She joined the WTHR-TV 13 Eyewitness News Investigators team in 2003. Wanda Skaggs had a 23-year career as a broadcast journalist, most prominently as assignment editor and a producer for WTHR-TV 13.

In 1992, William Mays partnered with longtime broadcaster Bill Shirk to launch WAV-TV Hoosier 53. It was the city’s first over-the-air television station to have Black ownership. Programs such as The Hoosier 96 Video Mix and The Noon Show with Amos Brown became popular among segments of both Black and white viewers. WAV-TV was sold to Maryland-based media conglomerate Radio One in 2000.

Sister Sue Jenkins, an African American Roman Catholic nun from Indianapolis founded the Kingdom of God Broadcasting Network. Based in Indianapolis, she founded two Christian television stations in Indiana, supported with a grant from the National Association of Broadcasts. Those stations mostly aired evangelical Roman Catholic programs. Jenkins was also program host and executive producer of Born Anew, a national award-winning series.

From the 1980s stations added African Americans to their staffs. Among them was Grace Trahan, morning and midday news anchor for WRTV-TV 6 (1994); Anthony Calhoun, who joined WISH-TV 8 in 1998 and later became its lead sports anchor; and Andrea Morehead, longtime weeknight anchor for Eyewitness News on WTHR-TV 13. Other Black television personalities included health reporter Stacia Matthews, who enjoyed a 23-year career with WRTV-TV 6; Glendal Jones and Kevin Bradley of WTHR-TV 13; and Cheryl Parker and Derrick Wilkerson of WXIN-TV FOX 59.

As the 21st century arrived, Indianapolis television stations continued to increase the diversity of their staff. Ericka Flye joined WRTV-TV 6 in 2000, where she appeared for more than two decades as an anchor and general assignment reporter. In 2001, Mike Corbin became a weekend anchor and reporter for WISH-TV 8. Steve Jefferson joined the Eyewitness News team of WTHR-TV 13 in 2002. He received notoriety as the station’s crime beat reporter. In 2005, Deanna Dewberry joined WISH-TV 8 as co-anchor for News 8 at Noon and 5 p.m.

Some personalities from local stations went on to earn national notoriety. Indianapolis native Janet Langhart cohosted the Boston-based talk show Good Morning, which was syndicated in 72 markets. Linsey Davis, who joined WTHR-TV 13 as a weekend anchor in 2003, later became an anchor for ABC News Live Prime, which became the network’s first-ever streaming evening newscast. Davis has also been a correspondent for World News Tonight, Good Morning America, 20/20, and Nightline.

In 2019, Indianapolis native DuJuan McCoy made history when his company, Circle City Broadcasting, purchased WISH-TV 8 and WNDY-TV 23 from Nexstar Media Group for $42.5 million. McCoy, who began his broadcasting career with WTTV-TV 4, is the first African American to become sole owner of television stations in Indianapolis.

Radio Media

Although radio had become a popular source of entertainment in the 1930s, Indianapolis did not have a radio station focused on Black listeners until 1968. On January 22, 1968, went on the air as the city’s first full-time (24-hour) African American radio station.

, a prominent African American physician and civic leader, gained ownership of the station in 1970, making it completely Black-owned. In addition to showcasing songs by Black artists, Lloyd instructed the station to increase its focus on news and solutions to challenges facing the city’s large African American community.

Although WTLC was the only local Black-owned station, other stations provided occasional opportunities for African American leaders to reach new audiences. During the early 1970s, Father , a prominent educator, spiritual leader, and civil rights activist, hosted three popular series including The Afro-American in Indiana, Reflections in Black and Black Heritage on , a public radio station affiliated with . Episodes of the programs featured high-profile guests, discussions on various topics, and coverage of major events such as conventions.

From the 1970s to the early 1990s, WTLC-FM was known as “Power 105.7,” and became the home of popular disc jockeys such as Spider Harrison, Rickie “Solid Gold” Clark, Thomas “Sparkle Soxx” Griffin, “Super Jay” Johnson, and Geno Shelton. Later additions to the “WTLC Air Force” included Tony Lamont, DJ Smooth, Amp Harris, and Brian Wallace.

All these radio personalities operated as local celebrities in the Black community. When not on the air, they appeared in advertisements, hosted television shows, and became major concert promoters. They also worked as disc jockeys for local events and volunteered their time as emcees for community fundraisers.

Radio stars would often broadcast “live on location” next to the WTLC van at events throughout the city, offering free concert tickets or samples of new products to promote the station. The energy and hype surrounding these broadcasts became a popular fixture of the Black entertainment scene.

From the 1980s to the early 2010s, Black on-air personalities at other stations included Kelly Vaughn, cohost of the top-rated Steve & Kelly morning show on soft rock/smooth jazz station WTPI-107.9 FM for 18 years. Vaughn later appeared as the news and community affairs director for WYXB-B105.7 FM. Ralph Adams was another longtime icon of Indianapolis radio, hosting jazz programs for WIAN and then for 26 years on -FM 88.7.

Eric Garnes joined WENS 97.1-FM in 1982. He anchored a sports talk program and hosted Night Love Songs, a successful evening show. In 2001, Garnes joined soft rock station WYXB-FM B105.7, where he was best known for The Lunchtime Hystery Mystery. Lonnell “King Ro” Conley hosted Blues with a Feeling on WPZZ-FM from 1984 to 1989, and then on WTLC from 1989 to 1999. He was later elected to the Indianapolis City-County Council.

Radio programs went beyond entertainment and became a significant source of news for local African Americans. WTLC-FM hired a skilled news team. Segments hosted by personalities such as Wendell Ray and Vickie Buchanon provided news and coverage of local events.

Talk shows also emerged as a popular radio format. Each Saturday, civil rights leaders such as Rev. used WTLC’s Operation Breadbasket to focus on urgent issues facing Black residents and mobilize listeners for involvement in community organizations. Sunday mornings included The Chat Room, hosted by Terri “Terri D” Durrett, the station’s morning news anchor. In more recent years, WTLC has featured Access Indy, a Sunday news and talk program hosted by Kim Wells.

From 1995 to 2004, Willie Frank Middlebrook issued powerful calls for racial and economic justice with guests on WTLC’s hard-hitting talk show The Bottom Line. It grew from a two-hour Saturday program to being featured on weekday afternoons. Middlebrook’s brash and honest approach to broadcasting quickly gained a large audience following. Talk shows on other stations during the era included the nationally syndicated Sister Talk on , with host Linda “L. C.” Clemons.

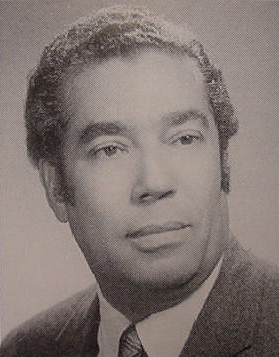

Amos Brown was often recognized as the most prominent Black journalist and radio personality in Indianapolis. He was among the first broadcast journalists to merge the news and talk show formats on local radio. Brown’s 40-year career in Indianapolis began in 1975 when he joined WTLC-FM as a sales associate.

By 1981, Brown had been promoted to assistant station manager and started Morning with the Mayor. This groundbreaking monthly program gave listeners a chance to hear directly from city leaders about their important issues. Brown launched The Noon Show on the new WTLC-AM station in 1992. It became the city’s first African American radio talk show. Brown described the show as “a vehicle for African Americans to express their hopes, fears, dreams, and frustrations.”

After a stint of directing news at Hoosier Radio and WAV-TV 53, Brown returned to WTLC-AM, where a large audience listened to him as host of Afternoons with Amos. His show boldly highlighted community issues, featured influential guests, and helped concerned callers quickly find solutions. Brown fought for causes important to the African American community as well as improvements for the city at large. His sudden death in 2015 was widely mourned by Indianapolis residents across political, racial, and economic lines.

Major changes occurred for African Americans on the radio during the 1990s. Bill Mays joined forces with radio station operator and escape artist Bill Shirk to launch WHHH-FM in 1991. Known as “Hoosier Hot 96.3,” the station competed directly with WTLC-FM for the city’s Black radio audience, especially among younger listeners. For example, WHHH-FM played hip-hop music, while WTLC-FM did not, with producers viewing rap songs as incendiary and inappropriate for its classic R & R&B/Soul format. Mays and Shirk expanded their broadcast holdings to include WHHH-FM, oldies station Kiss 106.7, Smooth Jazz WYJZ-FM 100.9, and WAV-TV 53.

WTLC also gained support among listeners who enjoyed gospel music and attended Christian churches. Historically, this has been a large segment of the African American radio market. Gospel music executive Al “The Bishop” Hobbs became general manager of the station and helped create WTLC-AM-1310 “The Light” in 1992. The new AM station featured classic and current gospel music, live sermons from prominent ministers, and inspirational talk shows. Some of the best-known gospel music radio personalities on WTLC included Burnetta Sloss-Tanner, Robert Turner, Delores “Sugar” Poindexter, Faith Dixson, and Donavan Hartwell.

Throughout the 1990s, many of the city’s Black listeners started their day on WTLC-FM with the Breakfast Club featuring Guy Black, which included a fast-paced mix of music, comedy, and local news. An evening segment known as The Soft Touch (later The Quiet Storm) featured R&B love songs with “Mr. Lover Man” Jerry Wade.

WTLC was sold to the Indianapolis-based media company in 1997. Then in 2000, both WTLC and WHHH were purchased by Maryland-based Radio One, an African American-owned national broadcasting conglomerate.

WTLC-FM began to rely more on nationally syndicated programs such as The Tom Joyner Morning Show, which itself was replaced by the Ricky Smiley Morning Show in 2020. Hour of Power with Reverend Al Sharpton was added to Saturday mornings. However, between 2000 and 2020, WTLC-FM still featured well-known local talent such as First Lady Khris Raye, assistant program director and midday personality; as well as Karen Vaughn, JC, Kenny Kixx, Donna Schiele, Jules, and Eliott King. During the same era, WHHH-FM (Hot 96.3 FM), the city’s other major Black station, included popular personalities such as Jillian “JJ” Simmons, midday host and assistant program director; and mix DJ Rusty Redenbacher, who later moved to WTLC-FM.

Digital Media

In the 21st century, journalists confronted consumer demand for more news from online sources such as Internet sites, blogs, and social media platforms.

Attorney and radio personality Abdul-Hakim Shabazz used his public policy experience to launch IndyPolitics.org, a premier political blog. Information featured on IndyPolitics.org was frequently cited by other journalists as well as political figures in both major political parties. It has been listed by the Washington Post as one of America’s best political blogs. Abdul-Hakim Shabazz has also been host of the Abdul at Large talk show on WIBC-FM 93.1 and a contributor to numerous publications.

In 2017, Black Indy Live went online as one of the main grassroots sources of local news provided. Among its contributors were informed citizens and community activists. Claiming more than 400,000 readers, Blackindylive.com promoted itself as a venue for authentic, relevant, and breaking community-based news “often ignored by mainstream publications.”

Media Associations

African Americans from all sources of media in Indianapolis shared a common goal of advocating for the hiring of more Black journalists to reflect the diversity of the city’s media market. In 1991, the Indianapolis Association of Black Journalists was formed for mutual support and to mentor the next generation of Black media professionals.

IABJ’s stated purpose was to “unite Black journalists” in dedication to professional excellence, diverse and inclusive news coverage, and equality in the media industry. The non-profit organization also facilitated programs to prepare Black students for careers in journalism and media-related fields through mentoring and scholarships.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.