Adaptive uses of vacant historic religious buildings have saved notable examples of sacred architecture. In 1929, there were 461 buildings of worship in use within the City of Indianapolis. Sixty years later, there were approximately 575 such buildings actively used within the Indianapolis boundaries.

Although there were more worship centers in 1989-1990, the congregations were largely different than those in 1929, and many of the locations had shifted from the center city to post-World War II suburbs of . It appears that a majority of the 1929 houses of worship were abandoned and demolished. Many of those congregations that chose to remain in their pre-1929 buildings faced declining numbers as their members moved to suburbs. The change in identities of active congregations between 1929 and 1989 suggests that many of the 1929 churches and synagogues disbanded or merged with other congregations. Some vacant buildings were purchased by newly organized congregations, but others were razed as neighborhood populations declined.

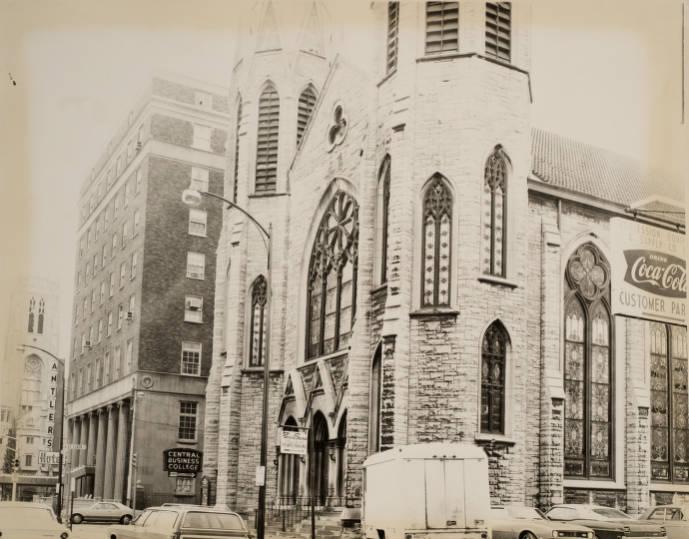

The abandonment of 19th- and early 20th-century religious architecture in Indianapolis was part of a national and even international trend in Western societies after World War II. In the United States, redundancy of houses of worship has been experienced in both urban and rural areas. In Indianapolis, preservation advocates, developers, and individuals who enjoy living in old buildings have responded creatively to the threat of increasing numbers of vacant buildings of worship in the city. One of the earliest adaptive uses of a vacant historic church occurred in 1947, when the Indiana Business College acquired the former Meridian Street Methodist Church at 802 N. Meridian Street (1905) and converted the Gothic-style sanctuary and educational wing to classrooms and offices for its operation. After the business college left the building for new quarters in 2002, preservation advocates successfully promoted its adaptive use for apartments.

In 1988, the Phoenix Theater acquired the vacant former First United Brethren Church (1907) at 749 N. Park Avenue and converted it to performance spaces for its theatrical productions. Phoenix Redevelopment Partners LLC purchased the property and converted it into luxury condominiums when the Phoenix moved to its new home at the northeast corner of Illinois and Walnut streets in 2018.

In 1985-1986, the Fletcher Place United Methodist Church, an 1873 Gothic landmark at 501 Fletcher Avenue, closed. Eventually, after use as a banquet center, investors acquired the building and rehabilitated it for a new use between 2007 and 2013 as the Fletcher Pointe Condominiums. Another example of residential adaptive use occurred with the former All Souls’ Unitarian Church, 1455 N. Alabama Street, constructed in 1914 and 1929. Two faculty members, Mark Richardson and Linda Goodine, purchased the vacant building in the 1990s and converted it into a residence for themselves, a studio, and a rental space for artists. Down the street, the former First Friends Church at 1241 N. Alabama Street, constructed in 1895, stood vacant for several years after 2000 and faced demolition after its roof collapsed. Between 2011 and 2015, a developer rebuilt the structure and converted the interior to apartments.

Probably the most impressive and influential of all of the adaptive uses of historic religious architecture took place in 2010 and 2011 at 1201 Central Avenue. There, acquired the vacant former Central Avenue United Methodist Church, built between 1891 and 1922. Through the philanthropy of the Cook family of Bloomington, Landmarks rehabilitated the whole complex, adapting it for use as a center for cultural and arts programming, rental for private events, and offices for the preservation organization.

Other notable adaptive uses include the 2012-2014 conversion of the long-vacant St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (1879) at 540 N. College, first for architectural offices by the A2SO4 firm and then for the St. Joseph Brewery; conversion of the 1910 Second Christian Church at 702 W. 9th Street, built by an early African American congregation, to a residence by Lauren and Joe Harsin in 2013-2015, after intervention by Indiana Landmarks; and the adaptive use in 2011 of the former at 711 N. Pennsylvania Street (1875 and 1885) by Scott and Barriebarbra Wheeler to a rental center for weddings, the Sanctuary. In 2018, Cyrus Jafari opened the Cyrus Event Center in the former First Evangelical Church, 237 N. East Street (1882). Indiana Landmarks in 2014 acquired the vacant former temple at 3359 Ruckle Street (1925) and is seeking an adaptive use for the Neo-Classical building.

After advocacy for preservation by Landmarks, Van Rooy Properties acquired the former Phillips C.M.E. Church at 1226 Dr. Martin Luther King Street (1924), a notable African American building. In 2015-2016, Van Rooy adapted it for apartments.

In 2022, the Hampton Inn by Hilton and Homewood Suites by Hilton opened on the on the historic site of . Bethel’s Vermont Street Church, which was built in 1869, was preserved and incorporated into the site.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Glass, J. (2022). Adaptive Reuse of Religious Architecture. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 3, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/adaptive-reuse-of-religious-architecture/.

MLA:

Glass, Jim. “Adaptive Reuse of Religious Architecture.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2022, https://indyencyclopedia.org/adaptive-reuse-of-religious-architecture/. Accessed 3 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Glass, Jim. “Adaptive Reuse of Religious Architecture.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2022. Accessed Mar 3, 2026.https://indyencyclopedia.org/adaptive-reuse-of-religious-architecture/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.