Photo info ...

Credit: Indianapolis NewsView Source

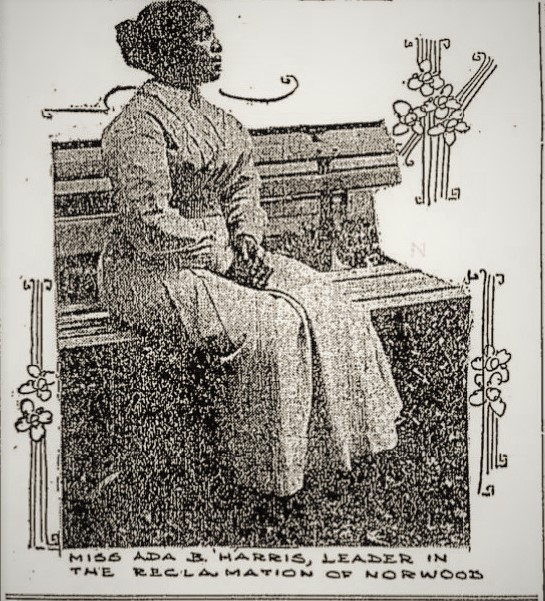

(Aug. 15, 1866- Sept. 12, 1927). Ada Harris was born in Campbell, Kentucky, to Robert Harris and Anna Tolliver. At some point in her childhood, she moved with her mother to what would become Indianapolis’ neighborhood, located at the center of the Black community on the near westside. In 1888, she graduated from Indianapolis High School, later known as . She then worked as a teacher at the segregated Center Township School No. 5, a one-room building located in the neighborhood, a Freetown located south of Prospect Street and east of the on Indianapolis’ near-southeast side.

Aside from teaching, Harris possessed an entrepreneurial spirit. In November 1893, she filed for a U.S. patent for the first comb-style hair-straightening device. Harris took her prototype and patent drawings to the California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894, an extension of the World Fair tours famous for showcasing innovations from around the world. She displayed her creation at a booth, hoping to find investors to back the project or a company to buy her patent, which the U.S. Patent Office eventually approved in 1895.

Harris’ civic engagement intensified after the patent approval. While she continued to teach, she and three women founded the Idle Hands Needle Club, which worked to solicit fuel, food, and clothes for the poor in Norwood, the area surrounding on the near westside, and other Indianapolis neighborhoods.

During the 1890s, when the craze swept America and Indianapolis, the African American newspaper, the called Harris a “modern” woman for owning a bicycle and riding it from her home on the near westside to where she taught in Norwood. She encouraged other women to become more independent by leading female cycling parties on a path from Indianapolis to MILLERSVILLE, then a separate community located northeast of the city.

Harris’ progressive activities extended beyond helping Norwood’s youth to involvement in many other organizations for the betterment of society. She was a founding member of the Corinthian Baptist Church’s Women’s Club, later called the Woman’s Civic Club, in 1894. She also was an officer of the Phyllis Wheatly Club, the Murphy Temperance League, and the Christian Endeavor Society of . Harris was a member of the , which concentrated on providing care for African Americans who suffered from tuberculosis. She served on the civics department of the , affiliated with the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, and was a member of the committee that drafted one of the organization’s constitutions. Harris also wrote for the city’s two Black newspapers, the and the Indianapolis Freeman.

In 1903, Harris became principal of Harriet Beecher Stowe School IPS No. 64, which was established to alleviate overcrowding at School No. 5. With this assignment, she had responsibility for the direction of the largest Black school in Marion County.

In the early 1900s, Harris moved to Norwood, where she focused many of her civic activities. In 1905, she founded a boys’ club called the Lookout Club. The club raised enough money to purchase property and to construct the Norwood Community Center, which included a gym, a reading room, and bathrooms. The center became home to the Lookout Club in 1908. Pride Park stands in the location today. Harris also raised money to buy a Norwood community grocery store. In 1909, the brought attention to these efforts. “My greatest ambition is for my race,” Harris told the Star reporter. “I want to see my people succeed. I want to see them have equal chances. . .. I shall have spent my life for my race.” In 1912, the year that Indianapolis annexed the neighborhood, Harris headed the city’s first library for African Americans, which opened at the Norwood Community Center.

In 1914, Harris’ church club, the Women’s Civic Club boasted more than 300 members. The club merged with the Indianapolis branch of the —one of few in the country that allowed women to hold leadership positions. After becoming a public notary in 1917, she hosted voting registration parties to register Black women to vote as well as seminars to answer the question of women’s suffrage. Harris continued to organize activists and run the Norwood community grocery store at the time women gained the vote.

A lifelong learner, Harris graduated from , then still located in the neighborhood, in 1926, with a degree in education. She then took a teaching job at Rockville, where she died after suffering a paralytic stroke. She is buried in .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.