Photo info ...

Credit: The Indiana Album: Swain-Brown Family Collection View Source

(1835-Dec. 31, 1919). Rachel Swain was born in Randolph County, near Richmond, Indiana to Quakers Anthony and Rhoda (Lane) Way. She attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio and married Theron Swain, a fellow-Quaker from Union County, Indiana in 1860. The Swains had two sons, Fremont who became a physician and Harold who became an attorney.

Widowed in 1869, Swain followed her two sisters into the medical profession. Swain graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania with an M.D. in 1871. She graduated from Northwestern University Women’s Medical College in Chicago in 1883.

At the time Swain studied in Philadelphia, it is likely her Quaker-driven moral sensibility to uplift the ill, homeless, and unstable was amplified by the Quaker ideals that influenced the city. Philadelphia had long been at the center of the country’s premiere medical research and education facilities. The city was also home to the Thomas Story Kirkbride approach to treating those with mental illness. Known for his humane approach to treating mental health patients, Kirkbride advocated for better facilities providing sunlight and sanitary rooms, limited use of restraints, and increased access to recreational and educational activities. Swain’s approach paralleled Kirkbride’s: she became a proponent of treating ailments with interventions such as diet, exercise, massage, electricity, and hydrotherapy. Furthermore, Swain advocated the use of alternative therapies and relied on drugs and surgery as a last resort.

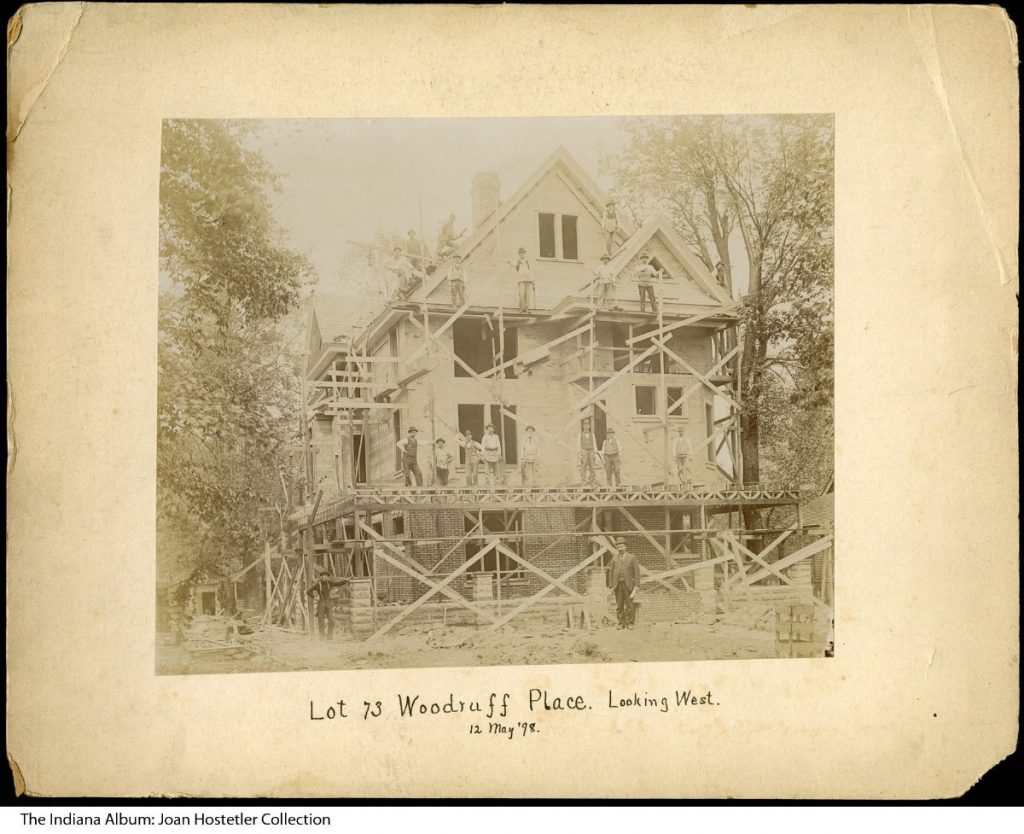

Swain operated a private hospital, Swain Sanitorium, at her Indianapolis home on N. New Jersey Street in the early 1880s. At this hospital, Swain implemented the tenets of living with pure air, pure water, and pure food for her patients. She ensured those under her treatment received much of their care outdoors and all their food from sanitary kitchens. To allow for daily observation and treatment of her patients, she limited the number individuals she cared for. In 1898, Swain moved her hospital to the neighborhood and renamed it Swain’s Home Health Sanitorium.

Swain published many articles about her treatment methods in health and medical journals. She also wrote several cookbooks in which she stressed a healthy diet to promote mental hygiene. A quote about diet in the Swain Cookery with Health Hints, published in 1895, reveals her forward thinking about the contemporary farm-to-table movement:

In most chronic and nervous diseases, perversion of nutrition is a leading symptom. Improvement in nutrition is usually the measure of recovery. Intelligent supervision of the diet is as desirable as it is difficult. We aim to have our table supplied with the best that the excellent markets of this fertile region afford, so prepared as to retain the full food value, so selected as to avoid the derangements arising from improper combinations, and yet afford a well-balanced dietary, and so varied as to avoid the monotony of the average table.

Swain continued to work until 1910. Her legacy of plant-based diets, physical exercise, natural medicines, and balanced nutrition are key lifestyle choices that contemporary doctors, nutritionists, and exercise gurus continue to advocate for today.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.