Indianapolis is home to multiple rivers and streams including its main waterway, the . The waterways of Indianapolis are part of the Wabash River Drainage Basin, which covers two-thirds of Indiana. Most of Indianapolis lies within the White River Subbasin, except for about 45 square miles along the southeastern edge of the city that drains into Buck Creek, a tributary of the East Fork White River. The major streams in Indianapolis are the White River and its two principal tributaries, , and Eagle Creek. Other large tributaries include Buck, Mud, Indian, Williams, Crooked, Little Eagle, Lick, and East Fork White Lick creeks, and Pleasant Run.

The surface-water system of present-day Indianapolis is significantly different from the conditions found by early settlers. In 1821, the area was covered with stands of hardwood, and the poorly drained uplands were dotted with ponds and marshes. The slow release of stored surface water and the seepage of groundwater into stream channels helped maintain streamflows during periods of little or no rainfall. The natural conditions changed drastically as settlers cut the timber, dredged streambeds, and drained the land. The loss of the water storage capacity of forests and marshes contributed to an increase in storm runoff to streams during heavy rains and a decrease in streamflow during dry periods.

Modern urbanization has further modified streamflow characteristics. Roads, buildings, and other structures increase storm runoff by covering the ground with relatively impervious surfaces, thereby decreasing the effectiveness of underlying soils in absorbing and slowly releasing excess water. A complex network of storm drains, ditches, and culverts quickly routes the increased volume of stormwater to the city’s waterways. The dredging and straightening of many watercourses further increases drainage efficiency, and levees and floodwalls confine excess water to engineered channels.

Variability in flow is a notable aspect of both natural and artificial waterways. During dry weather, many creeks in Indianapolis cease flowing. In contrast, normally placid streams can be transformed into raging torrents after heavy rains. Daily streamflows recorded on several tributaries of White River range from zero to more than 3,000 cubic feet per second. The daily flow on White River near ranges from 49 to 58,500 cubic feet per second; flow on Fall Creek at ranges from 8 to 22,000 cubic feet per second; and flow on Eagle Creek near Lynhurst Drive ranges from zero to 28,800 cubic feet per second.

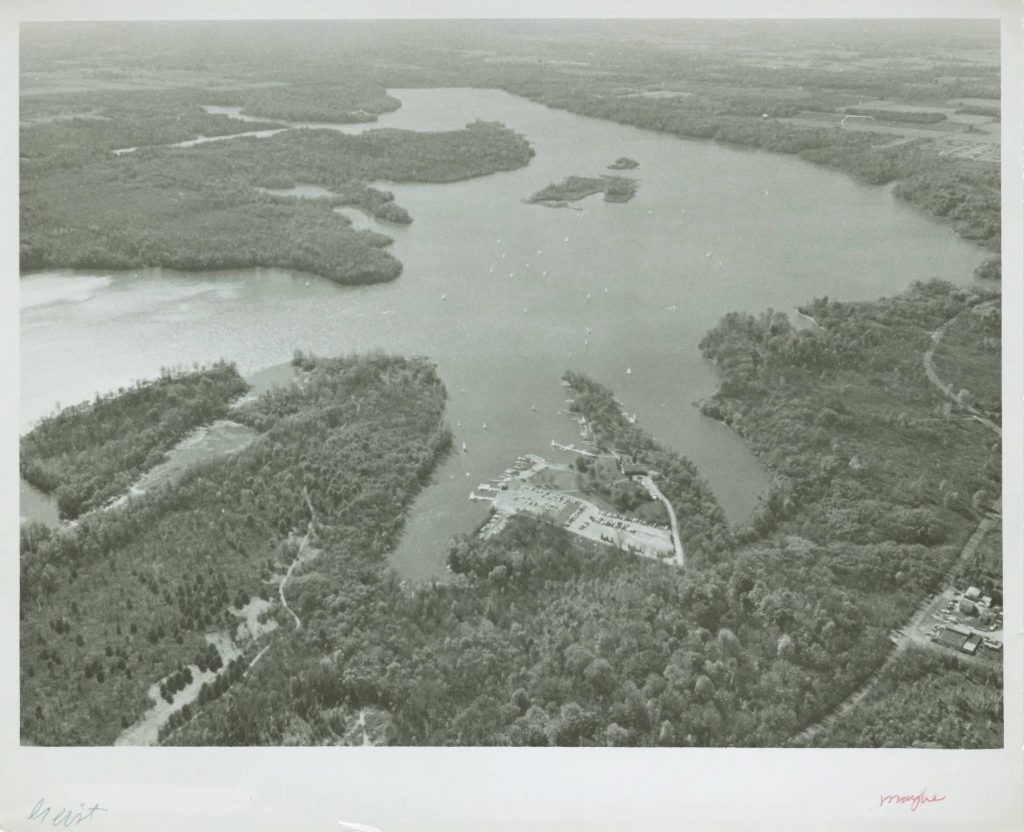

Controlled releases of water from three reservoirs constructed between 1943 and 1968 have helped stabilize flow in downstream reaches by reducing flood intensity and increasing dry-weather flow. in northeastern Indianapolis releases water to Fall Creek, and Eagle Creek Reservoir on the city’s northwest side supplements flow in Eagle Creek. Streamflow in White River in Indianapolis is augmented by releases from into Cicero Creek, a major tributary entering White River in . The (now part of ) constructed Geist and Morse reservoirs for water supply purposes, whereas the City of Indianapolis built Eagle Creek Reservoir to alleviate downstream flooding and provide water supply storage.

The diversion of streamflow for public and industrial water supply is a major water management feature of Indianapolis. Of the public water utilities serving Marion County, and Indianapolis are primarily supplied by surface water from streams and reservoirs. Multiple power generating stations in Indianapolis rely on White River as a source of cooling water. A few businesses and industries also withdraw water from White River or other major streams, although most companies that supply their own water rely on groundwater.

Citizens Energy Group is the largest water utility serving Indianapolis and has the largest total surface water usage. Before it was part of Citizens, the IWC began to supplement its groundwater pumpage in 1904, by treating water from the White River for use as a public water supply. Surface water pumpage steadily increased, and by 1985, the utility obtained more than 90 percent of its total average daily use of 100 million gallons per day from the city’s stream systems. The diverts water from White River at and flows southward to Citizens’s White River Treatment Plant near 16th Street. Excess water in the canal which is not taken into the treatment plant is discharged into Fall Creek south of 21st Street. Citizens’s other intakes are located on Fall Creek at Keystone Avenue and on Eagle Creek Reservoir at 56th Street. The town of Speedway pumps water from Eagle Creek in conjunction with its groundwater supply.

The combined effect of the large water supply diversions from White River and Fall Creek can noticeably reduce minimum daily streamflow downstream of the diversions, particularly during dry summer months. Analyses of streamflow records show that minimum daily discharge and statistically low flows on White River at Morris Street (located downstream of the water supply diversions) are lower than comparable flows at the unaffected Nora gauging station, located 18 river miles upstream from the Morris Street gauge. During the drought year of 1941, as much as 83 percent of the water in White River was diverted for water supply; however, most of it was returned downstream as treated wastewater.

Average to low streamflows on White River and Fall Creek can be affected by several instream dams. The Broad Ripple dam in White River ensures sufficient flow into the canal. The pooling of streamflow behind instream dams in White River near Washington Street and near Harding Street ensures adequate channel storage to support water withdrawals at two power plants. Several low dams in other reaches of the White River and along Fall Creek similarly help maintain channel storage.

The water quality of streams in Indianapolis is influenced by the return of unused diversions, the discharge of treated municipal and industrial wastewater, return flow of cooling water from power plants, combined sewer overflows, erosion and sedimentation from construction sites, chemical spills, wastewater bypasses, and nonpoint urban runoff from streets, parking lots, rooftops, and other surfaces. Before the 1980s, White River through downtown Indianapolis and several segments of Fall Creek, Eagle Creek, , East Fork White Lick Creek, and other tributaries were severely degraded. On the White River, poor water quality conditions often existed for more than 50 miles downstream of Indianapolis, and fish kills were frequent. Contaminants commonly found in the city’s major waterways included fecal bacteria, dissolved metals, ammonia, organic substances, nutrients, suspended solids, and toxic substances such as chlordane and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

By the early 1980s, the quality of the White River and its major tributaries had started to improve. Many industries and all but one of the incorporated communities in Marion County that formerly discharged directly to White River or its tributaries were connected to sewer systems that lead to one of the two Indianapolis wastewater treatment facilities. Both facilities were upgraded to tertiary treatment in 1983, and many sewer defects and problems with the city’s wastewater effluent were corrected.

Although White River south of downtown Indianapolis remains of below-average quality by state standards, most segments of the river now support a diverse warm-water fishery, particularly smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, and channel catfish. In 1989, the Indiana State Board of Health lifted the fish consumption advisory for White River throughout Indianapolis that had been in effect for several years because of elevated levels of PCBs and chlordane in sediments and fish tissue.

The improvement in stream quality continued throughout the 1990s as regulatory agencies enforced the strict water quality standards passed in December 1989, by the Indiana Water Pollution Control Board. In 2006, the Tunnel project began as another solution to improving water quality by reducing sewer overflow into waterways with a 28-mile-long tunnel system designed to store the overflow for later treatment. The protection of stream corridors has received more attention, particularly as the popularity of river cleanups and related activities continue to draw participants from various conservation groups, universities, neighborhood associations, civic groups, and local agencies. such as Reconnecting to Our Waterways, the White River Alliance, , Friends of White River, , and Indiana Wildlife.

The improved quality of the city’s waterways has been accompanied by an increase in water-based recreation and economic development. Fourteen streams throughout the city were part of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Greenways Plan, implemented in 1993. Plans for the , under various stages of development since 1979, have encompassed White River and nearby lands in Indianapolis. The White River and its tributaries are included within several riverfront parks, and Eagle Creek Reservoir is a popular feature of . Boating and fishing are common along many of the city’s major waterways.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.