Indianapolis boasts a large array of post-secondary institutions, extending from traditional four-year colleges to a major urban university to populist academies. In the early 1990s over 60,000 students were enrolled annually in area colleges and universities.

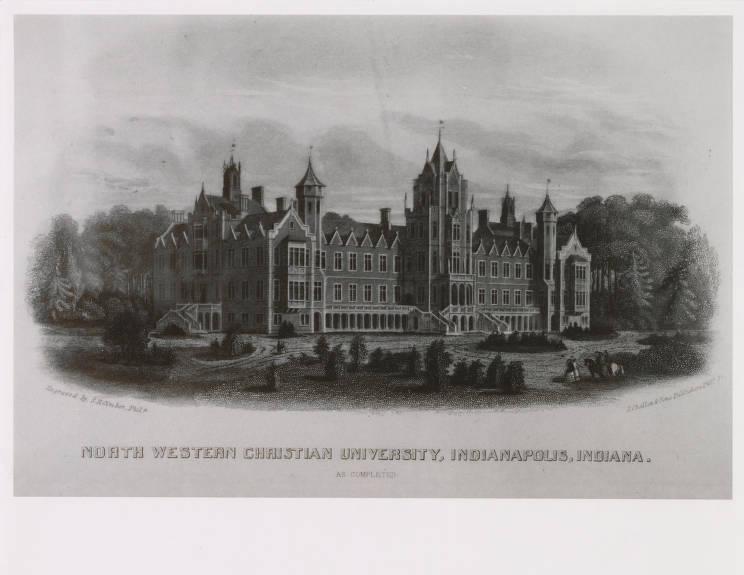

By the mid-1800s Indianapolis was developing into a major metropolitan area. Businessmen, lawyers, physicians, other professionals, and even the occasional entrepreneur hoped Indianapolis would achieve the status of a significant midwestern hub comparable to Cleveland, Detroit, or Pittsburgh. Higher education, however, did not seem to be a part of the plan. development of North Western Christian University (later renamed ) in 1855 marked the only successful establishment of a major college or university in the city in the 19th century. The reasons for this lack of development are interesting to consider, especially given the common practice of college “boosterism,” using the promise of a college or university to promote a town or city to outside investors.

Indiana retained a very rural flavor well into the 20th century. Most of its citizens lived outside of any city of significant size. In contrast to the westward migration common to most midwestern states, large sections of Indiana were ceded from the South, not the East. These southern-born Hoosier settlers brought with them an agrarian orientation toward family, land, and virtue coupled with a strong rural distrust of cities. A city, they believed, was inappropriate as a center for learning and serious study. The tradition of locating institutions of higher education in rural areas had started with Oxford and Cambridge in England, and most colonial colleges followed the example. It was no accident that the first state institution, Indiana University, was established as Indiana Seminary in 1820 in the isolated town of Bloomington. Even Butler, originally sited on the fringe of the , was relocated to the quiet suburb of , far removed from the center of urban distraction.

Although an attempt was made to move Indiana University from Bloomington to Indianapolis in 1840, strong arguments were raised in opposition. For one, the cost of living in the city was much greater. Board alone was estimated to be at least 50 percent higher. A second argument was straightforward—a relocation would cost at least $20,000, a very large amount of money at that time. Third, young men living in the city would have more “inclination to extravagance.” The fourth and concluding argument was simply that Bloomington was a “healthy” location while Indianapolis was “wicked.” Three more efforts to relocate Indiana University were made during the 19th century but none was successful.

When the idea of a land-grant agricultural college was first proposed in 1863, Indianapolis seemed a probable location, especially as the old was vacant and appeared to offer a suitable building. However heavy lobbying by Tippecanoe County legislators, the existence of several available buildings there, and the donation of $100,000 by John Purdue for the college persuaded the legislature to locate the institution in present-day West Lafayette. The preference for rural isolation continued. In 1870 Terre Haute was chosen as the site for the first major teacher training institution in the state, the Indiana State Normal School. Even 50 years later, when a branch site for teacher education was proposed in 1918, it was located in Muncie, 60 miles northeast of the capital city.

Boosters mounted a brief effort in 1896 to create a University of Indianapolis as a merger of Butler, the Medical College of Indiana (1878), the Indiana Law School (1893), and the Indiana Dental College (1894). The experiment actually began in 1902, foundered, and eventually failed in 1906. Two other local colleges did emerge in the early 20th century, however: the —known as Indiana Central College for much of its history—was founded by the Church of the United Brethren in 1902 (its present affiliation is with the United Methodist Church); and in 1937 , a Roman Catholic institution, moved to Indianapolis from its original home in southeastern Indiana.

Professional schools were more attractive to 19th-century Indianapolis leaders. These schools have reflected a long-standing interest of Indianapolis citizens in creating a city that would be a center for the development of business and commerce. Schools were established for the training of lawyers, businessmen, physicians, dentists, musicians, kindergarten teachers, veterinarians, and even telegraph key operators. As a railroad hub and the state capital, Indianapolis was a natural location for business-related activity in the state. The numerous schools dedicated to the professions mirrored the ambitious goals of the city at large.

By 1922 Indiana University and Purdue University accounted for 35 percent of the total college enrollment in the state, a figure that rose to 39 percent by 1939, just before . Private institutions around the state, both in number and diversity, accounted for a sizable proportion of the remaining college students. Even so, some 26 percent of Hoosier college students attended schools in other states. Indiana did not place great emphasis on the development of education during much of the 19th century and well into the 20th. By the late 1800s, Indiana ranked sixth out of ten midwestern states in the length of the school term and ninth of ten in the literacy of its population. It is not surprising, then, that the city experienced no stronger effort to pursue a major college or university; higher education in the state was not overly important through the mid-1900s.

The “G.I. Bill,” which emerged from World War II as one of the most significant entitlement programs in the history of American education, changed the nature of higher education in Indiana and Indianapolis. Not only were veterans given unprecedented opportunities to gain a higher education, but their offspring, the much-studied “baby boomers,” grew up with the expectation of attending college. As a result, the demand for higher education increased exponentially throughout the state during the 1950s and 1960s. But nowhere would the increase grow faster and be felt more strongly than in Indianapolis. The presidents of the two largest state universities, Herman B. Wells at Indiana and Frederick L. Hovde at Purdue, used the demand for higher education as an entrepreneurial opportunity to expand their respective institutions while also expanding the scope of state commitment and investment in the “Big Two.” Although extension courses had been offered by both Indiana and Purdue universities in Indianapolis since 1891, the new demand was unprecedented. Enrollments and campus size had increased so much by 1968 that Elvis Stahr, Wells’ successor at Indiana, recommended a separate chancellor to oversee the newly created (IUPUI).

Owing to the ready student population in the metro area and the vast opportunities for degrees, the IUPUI campus became the third largest in the state in a matter of a few years. The Indianapolis campus absorbed several of the professional schools in the Indianapolis area, notably the , the and the Benjamin Harrison School of Law, to name several examples. The medical complex of six hospitals and training centers connected with the IUPUI Medical Center boasts one of the largest medical training programs in the United States.

(Ivy Tech) is mandated to provide “occupational training of a practical, technical and semi-technical nature.” The school began regular operation in Indianapolis in 1966 and has offered programs in the capital continuously since that time. Ivy Tech’s Region VIII, which includes Indianapolis, enrolled almost 6,100 students in the fall semester of 1992. Several of the college’s programs of study are available at the region’s campus complex on North Meridian Street at Fall Creek Parkway, where the institution moved in 1983.

In the 1970s and 1980s, increasing numbers of older, nontraditional students and women students further ensured the sustained growth of higher education in Indianapolis. Enrollments spurred the growth of traditional schools such as Butler and Marian as well as the nontraditional and the “Learn and Shop” and “Weekend College” programs offered by IUPUI. As higher education became an opportunity for lifelong learning, the expansion of post-secondary education throughout the city at both state-supported and private institutions became less an afterthought and more a necessity. Despite a slow start, higher education in Indianapolis, in the latter years of the 20th century, has expanded rapidly. Indianapolis residents today can find classes, courses, and colleges to meet a wide range of educational needs.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.