Before the 20th century, private charity organizations customarily provided social services to school-age children. With new social theories of education and the professionalization of in the decades after 1900, schools increased their involvement. American education during the 20th and then 21st centuries has steadily expanded to include a wide array of social services for students. Services aimed at fostering physical and emotional well-being in students, from health care and hot lunches to career and psychological counseling demonstrate the ever-increasing responsibility that American society has placed on educational institutions. Indianapolis schools reflect this national trend.

The Rise of Social Work in Schools, 1840s-1940s

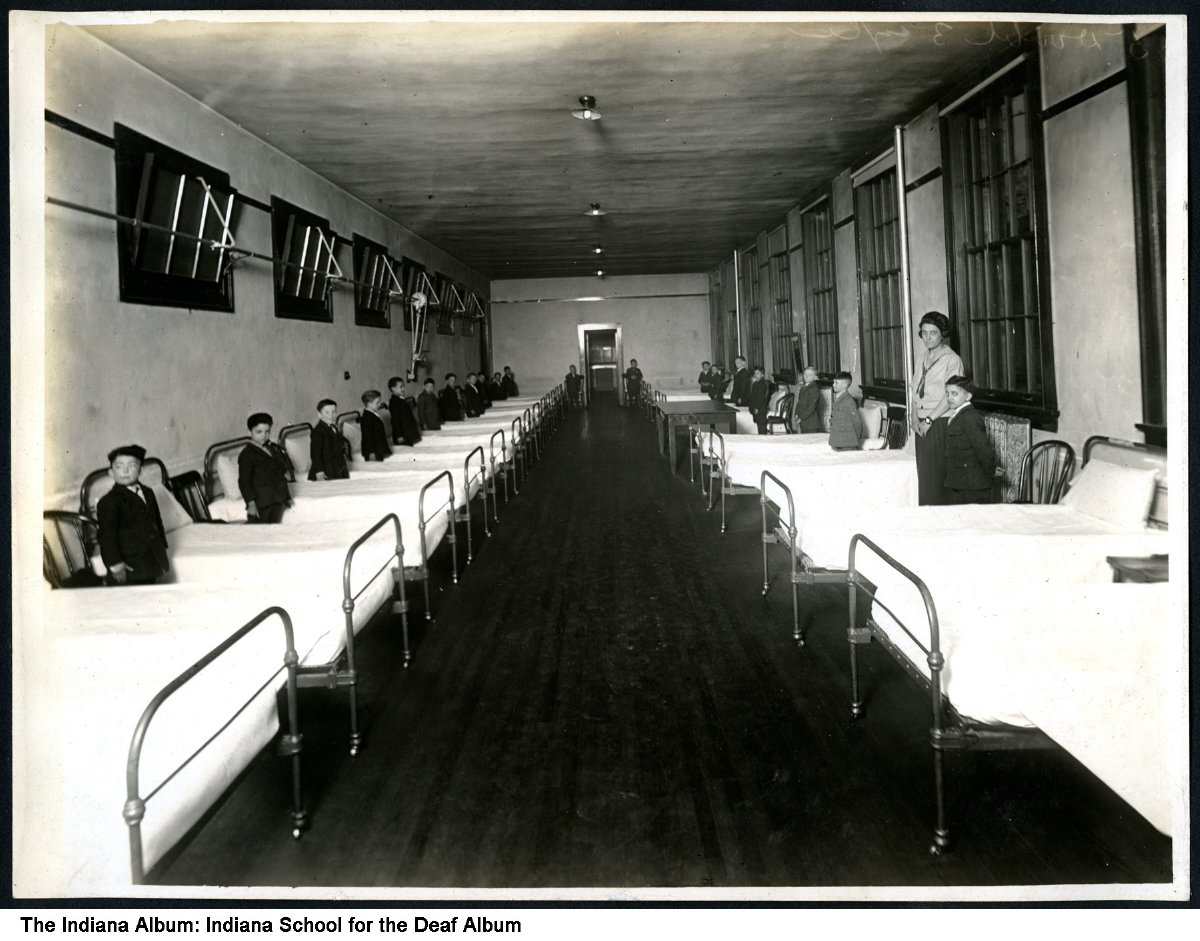

In the 1840s, the State of Indiana established the and the . Private charitable organizations in 19th century Indianapolis, however, provided most social services for school-age children. Voluntary groups provided food, clothing, safe spaces, and shelter for children in need. Schools developed for specific religious and ethnic populations. Catholic schools, usually connected to parishes, opened to provide low-cost education and faith formation for working-class Catholic families. The late 1800s and early 1900s saw Irish, German, and Italian immigrants settling in the city. St. John’s Academy for Young Ladies (1859) was the city’s first Catholic school; St. John’s School for Boys followed to serve local and boarding students from nearby towns. Catholic schools grew with St. Ann’s School for Negro Children (1892), Cathedral High School (1918), St. Joan of Arc (1922), and Ladywood School (1926).

Professional educators in the early 20th century began to organize and centralize with the goal of reaching as many students as possible. City government passed a series of compulsory attendance laws that, by 1920, covered all children between the ages of 5 and 16. The newly created Department of Attendance and Census (later the Social Service Department) monitored the number of school-age children who attended school. New social theories of education provided an impetus for schools to widen the scope of their activities. Many Americans placed a heightened emphasis on the role of education in molding children into functional, independent citizens. Schools, therefore, occupied a crucial position in alleviating problems of industrialization, such as truancy, undesirable behavior, poor health, and family disintegration.

Professionally trained case workers replaced truant officers as representatives of the schools’ desire to reach as many children as possible. Caseworkers came to view children’s failure to attend or poor performance in school as evidence of societal disruption, not individual shortcomings. Educators hoped to discover, analyze, and remedy these problems by implementing modern social work techniques.

The Social Service Department and teachers conducted home visits to evaluate children’s needs. If necessary, teachers referred families to nonprofit social service agencies. Some school-age children had to work to help support their families. The department developed a scholarship program that provided carfare, lunch money, and textbooks to students who otherwise could not afford to attend school. The Public Health Nursing Association provided health services in the schools. An array of social service agencies supported the school system with vocational, remedial, and language classes, including American Settlement () and . The and the sponsored Hi-Y clubs for high school students. expanded to many neighborhoods where local underserved youth received food, tutoring and education services, physical activity, and safe after-school spaces.

As social services expanded in the first decades of the 20th century, social workers examined factors influencing a student’s academic performance and social behaviors. They became integral to Indianapolis area public school systems with programs aimed at promoting health care, curbing undesirable behaviors and delinquency (criminal behaviors), and providing career guidance.

Federal Legislation and Change, 1946-1990

Following World War II, significant federal legislation provided funds that targeted support for children. The National School Lunch Act of 1946 established the free school lunch program, which continues today. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 funded Head Start, supported by child development research that shows that early intervention positively impacts cognitive and social-emotional development of low-income children. Head Start serves children from birth to age five, parents/caregivers, migrant children, children with disabilities, children who are homeless, pregnant women, and program administrators. Goals include language, literacy, physical development and health, and social-emotional development for kindergarten readiness. Today, programs exist in every county in Indiana.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, Title I, federally funds academic support for low-income K-12 students. Title II Part A funds increased academic achievement by improving teaching and school leadership quality. Title III funds English Learners and immigrant students with programming to help them achieve fluency in English and professional development for teachers and staff.

In the 1970s, schools became aware of the increasing number of “latchkey kids” who stayed home alone after school while their parents worked. Additional programming appeared in school districts to address concern for the safety of these students, carried out by school staff or by partner organizations. At-Your-School Child Services, Inc. (now, AYS, Inc.) partnered with Indianapolis Public School No. 70 in 1980 as Indianapolis’ first after-school program within a school building.

Since the 1980s, students arrived in schools from increasingly diverse cultural backgrounds with immigrants and refugees from Cuba, Myanmar (Burma), China, the Philippines, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mexico, and India. Social workers, counselors, and language specialists were responsible for providing them with support by connecting them to government and nonprofit agencies. School districts responded to the needs of the diverse language speakers by establishing English as a new language coordinator positions. organized family liaisons for different language communities. Community-based organizations, () and Exodus Refugee, offer tutoring programs and social services for youth.

The development of schools for specific religious and ethnic populations also continued in the last decades of the 20th century. In 1971, Hasten Hebrew Academy opened for pre-school through 8th grade Jewish students. MTI School of Knowledge, a K-12 school, became the first Islamic school in Indiana, in 1990.

New Insights, 1991-2019

In the 1990s, research that gave insights into positive and healthy youth development began to influence schools toward a focus on developmental approaches and away from juvenile delinquency prevention. Indiana Youth Institute offers training to help educators, social workers, and youth-serving organization workers incorporate these approaches.

Since 2000, societal norms demand greater understanding of students’ identities, spanning race, ethnicity, gender identification, and sexuality. Associations, districts, and schools now incorporate more training for school psychologists, social workers, guidance counselors, and educators to help them understand how to support diverse student bodies that represent a broad array of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, identities, and learning and accessibility challenges. Schools, , and incorporated affinity groups into school life to give students a safe space to explore their identities and to encourage inclusivity.

Reauthorizations of the 1965 ESEA Act occurred with the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002 and the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015 to further support low-income students. ESEA Title IV Part A created the Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants in 2015 with funds to enhance (1) Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), the arts, college, and career counseling; (2) access to technology and training; and, (3) safety and health support. Additional legislation assures those school activities and programs are accessible to students with hearing, learning, and mobility disabilities. A 2018 grant created the Future Centers in the (IPS) to help students explore their interests, determine college and career plans, and receive dedicated guidance for post-secondary planning.

Social changes continue to push schools to reimagine educational philosophies and expand school services. Twenty-first-century education is shifting away from earlier goals of uniform socialization of students and behavioral compliance that prepared students to be orderly citizens and fill jobs in factories and institutions with clear hierarchies. Today’s successful companies, highly effective nonprofit organizations, and the technology industry challenge K-12 schools to focus on developing skills like empathy, cross-cultural understanding, critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication to prepare students for jobs and growth industries.

Recent Trends and the COVID Pandemic, 2020-

Current disconcerting trends affecting youth in the information, or digital age, fall directly on school support services. These trends include a digital divide in which youth do not have equal access to technology and internet connectivity and the increasing use of technology in students’ personal and school lives as a potential risk to social-emotional health. To create equity around technology, Indianapolis’ public school systems provide all students with computer devices, and private schools offer assistance with devices for students receiving financial aid.

The unprecedented closure of schools, and the shift to online learning, across Indianapolis and the country in the spring of 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, brought to light the vast disparities of access to resources, familial economic fragility, and basic needs of students. In March 2020 the IPS district had to determine how to distribute food to its nearly 17,000 disadvantaged students who qualified for free and reduced lunch and who often relied on school for breakfast. IPS had to ensure all students had laptops and Internet connectivity. School social workers and staff distributed “hot spots” to make Internet connectivity possible for students without access.

These examples reveal the extent to which the scope of social services in Indianapolis’ schools has grown over the last century to incorporate students’ basic needs (food, safety, and transportation), physical and mental health needs, and preparation for college and careers. In an increasingly complex, global, and technological society, schools join families, nonprofit organizations, and a broad array of community partners with the goal of leveling the playing field for all youth.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.