From the earliest churches in Indianapolis religion and social services have existed in a complex and evolving relationship. As congregations of , , , , , , , and emerged, ecologies of care developed within and around them almost immediately. They did not provide the range of specialized help that we now call social services. But as congregations cared for their own members, supported families during crises, and ministered to the strangers who came into their local communities, they acted on the same impulses and responded to the same basic human needs for food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and counseling that people still manifest today.

Religion did not and still does not respond to these needs monolithically. Instead, particular groups, for example, the German Lutherans or the African American Baptists, responded out of their own traditions to the new challenges posed by a changing city. Further, these groups employed a variety of strategies to care for their fellow citizens. At various times they provided direct services, created alliances of groups to respond to larger social problems, motivated people to support secular means of care, invented new institutions that could provide new forms of help, and led in public advocacy for social change. While there are clear historical developments in the unfolding relationship of religion and social services—chief among them the professionalization and specialization of care and the muting of sectarian differences in the face of growing social need—the religious communities of Indianapolis continue to make use of all these strategies in the 21st century.

Early Patterns, 1820s-1870s

The 1816 Indiana Constitution created the earliest official public pattern of care for the poor and ill. It provided for several types of public assistance: (1) indoor relief, which placed indigent people on poor farms or in poor houses; (2) a farming out system, which paid private citizens to care for either individuals or groups of the poor; (3) an apprentice system, which placed minor children in the hands of adults; and (4) outdoor relief, which supported individuals and families in their own homes. In addition, the jails and county asylums housed the deviant and ill. At first, little differentiation occurred between poor, elderly, sick, insane, dependent children, and homeless poor. But as needs and resources grew, the state of Indiana founded public homes for the blind, the deaf and dumb, and the mentally ill in the 1840s.

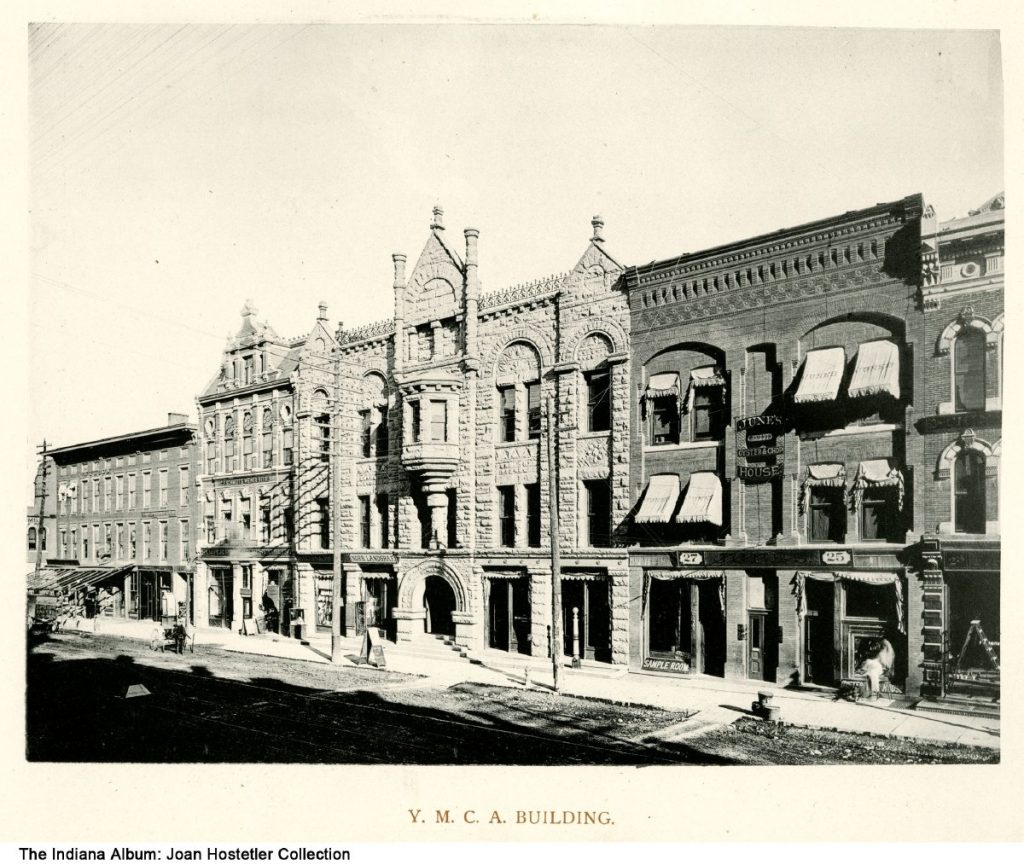

Private acts of religious individuals and their churches and synagogues have supplemented this minimal public infrastructure in countless ways. Gradually, private agencies were created to deliver forms of care that exceeded the capacities of individuals and local congregations. Already in 1835, the Indianapolis Benevolent Society was organized to provide food, clothing, and fuel for the poor. Orphanages like St. Vincent’s School and improvement organizations like the began to serve the city in 1851 and 1854 respectively.

These early forms of direct care were augmented by other strategies. For example, Methodists, at that time the largest denomination in the state, used their pulpits and publications to crusade against the two largest social problems of the age, alcohol abuse and slavery. In this way, they became the leading political advocates for and in the 1850s.

Major social disruptions like the Civil War and an economic depression in the 1870s occasioned a wide variety of institutional creativity. Orphaned children were housed in a new General Protestant Orphan Home after 1867. This home served more than 2,000 children between the time of its founding and 1941 when it merged with the Indianapolis Orphans’ Home () and the Evangelical Lutheran Orphans’ Home. By 1971 the orphanage had become the , a nonsectarian residential treatment center for victims of child abuse, neglect, and abandonment. This single institutional history illustrates patterns of secularization and shifting social need as its purpose changed along with its institutional identity. That pattern repeated itself numerous times as institutions begun under specific religious auspices became secular in the face of changing funding sources and social circumstances.

Sometimes congregations played distinctive roles in responding to new social needs. evolved under the leadership of Reverend into an institutional church, a new type of congregation that created programs within the church to address social needs. McCulloch’s leadership led to the creation of the Charity Organization Society (), which subsumed the Indianapolis Benevolent Society and the work of Indianapolis’ many churches and benevolent associations. McCulloch helped formulate legislation that created the State Board of Charities in 1889.

Religious Social Services and the Rise of Professional Social Work, 1880-1945

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, various religious groups continued to make their own contributions. Two Lutheran congregations created the Evangelische Lutherische Waisenhaus Gesselschaft in 1883, an orphanage that grew in the 20th century to become , a denominationally sponsored institution offering a full range of professional counseling services. The began its work in Indianapolis in 1889, providing food, clothing, shelter, and spiritual guidance. Its red kettles and brass bands are still in evidence in the city, and it operates substance abuse programs, homeless shelters, day camps, and senior citizens programs. Volunteers of America began locally in 1896 to promote self-sufficiency for the homeless and for others overcoming personal crises such as addiction and incarceration. Women formed the , which led to the founding of in 1893.

Due to the growing complexity of urban life and to professionalization championed by new forms of higher education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, social work began to lose its specific religious moorings and to take on the coloring of a secular profession. A formal training course begun in 1890 by the Charity Organization Society became a precursor to the establishment of the Indiana University Department of Social Service in Indianapolis in 1911, which in turn became the IU School of Social Work in 1966.

New institutions and new types of caregivers (service providers) quickly followed. In 1905, Anna Stover, a faithful member of the Disciples of Christ denomination, and Edith Surbey, a lapsed Catholic, opened in response to the urban revivalism they experienced at Chicago’s Moody Bible Institute. Christamore was an early settlement house opened to provide a new kind of care for the city’s immigrants and working class. These houses resembled college residence halls and offered a wide range of educational and cultural opportunities while they provided health clinics, baths, and kindergartens. Christamore emerged as a provider of a wide range of social services and finally evolved into a community center that still serves an Indianapolis neighborhood. Two other Indianapolis settlement houses, the American Settlement () and , both welcomed and depended on support from the Disciples denomination for leadership and financial help until Indianapolis reorganized its charity funding under the auspices of the Community Fund () in 1923.

Jewish families in need turned either to each other or created their own benevolent societies for help. They did not look to the COS, nonsectarian charities, or municipal relief programs. The Workmen’s Circle fraternal organization provided sickness and death benefits. The (JWF) formed in 1905 to consolidate the growing number of Jewish social welfare agencies in the city. By 1925, most Jewish residents were self-sufficient. Requests for aid dropped significantly and the Jewish Federation expanded into other areas.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Indianapolis grew to become a city of more than 300,000. Its reorganization of followed increasingly professional lines and reflected the impact of new federal legislation that created Social Security and a wide variety of public agencies in the 1930s. This new federal presence often seemed to overwhelm religious organizations, leaving them with difficult choices between significant new sources of support and the freedom to maintain their distinct religious identities.

African Americans and white citizens faced very different problems. Indianapolis was generally segregated, so African Americans had fewer educational, employment, and political opportunities. Although some charities assisted Black applicants, charities often expected Black citizens to take care of one another. Mutual aid therefore developed among the families who settled in Indianapolis as part of the Great Migration as African American self-help networks, churches, and clubs were essential to fill gaps in services. Unfortunately, institutions such as , founded and operated by the African American community, had difficulty remaining financially solvent.

The Post-World War II Era and Beyond, 1945-

Major institutions like and went through exponential experiences of growth and secularization in the post-World War II era even as they struggled to maintain their religious identities. Religious communities did not simply sit back and let the government and the professionals take over social service provision. In 1952 the Reverend Charles Oldham created the to care for indigent men in the inner city.

Episcopalians created the in 1975 to respond to adult female victims of child sexual abuse, rape, and domestic violence. Roman Catholics joined Episcopalians in 1987 to open the to minister to the AIDS crisis. Jewish philanthropists Clarence and created the to support programs for Jewish people in need. But religion often played behind-the-scenes roles in providing social services to the city. of Indiana, for example, used federal funds, along with private philanthropic dollars, to help build a national food bank network. In Indiana, this network supports more than 15,000 charities that provide direct help to hungry people.

Many of those who staff and volunteer throughout this complex network are recruited in local congregations, as are many of those who serve throughout the immense secular social service network of the city. Religion’s presence in social service continues to be immense and complex. They offer a range of services and boast a spectrum of heritages that no one could have predicted in the 1820s when the first religious institutions appeared.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.