In the early 1900s, waves of southern African Americans migrated to the North, some of whom settled in Indianapolis, specifically along Indiana Avenue. The city’s swelling Black population, increasing from 9,133 in 1890 to 21,816 by 1910, led to increased segregation and intensified social, employment, and health care needs for African Americans. During this progressive era, Black residents founded institutions to uplift the community, such as the , Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, and Lincoln Hospital. As these entities worked to meet the social and economic needs of the Black community, residents founded a local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1912 to challenge racial discrimination and advocate for civil rights.

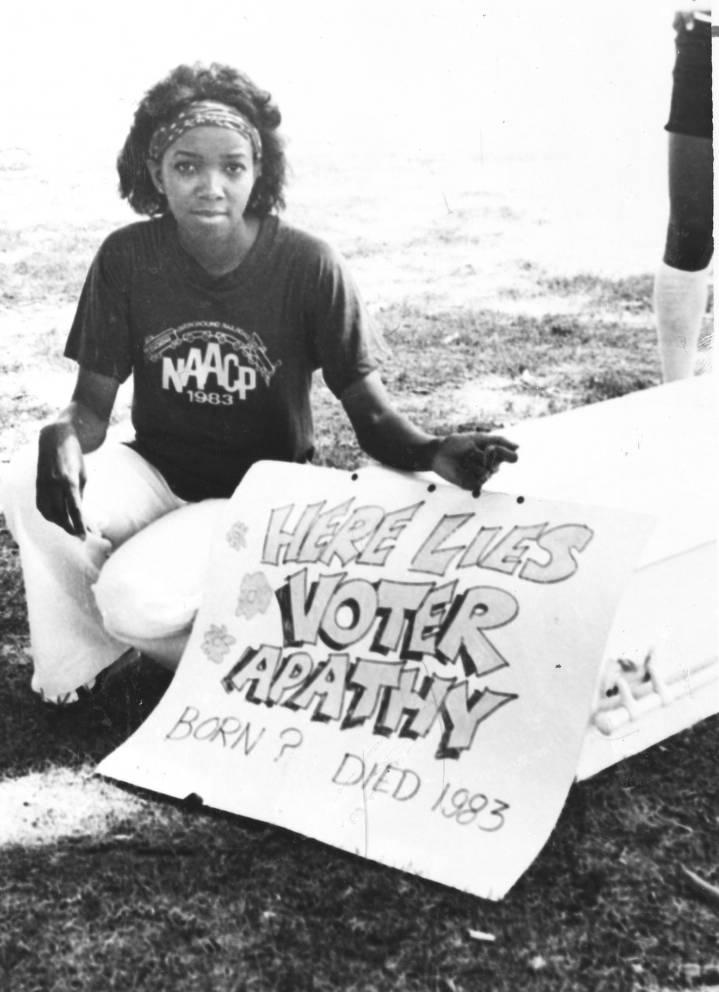

The local branch evolved out of the city’s Colored Women’s Civics Club (CWCC), which was formed in April of that year and led by President . NAACP newsletter The Crisis reported in July 1912 that the Indianapolis CWCC hosted one of the best meetings the national association ever participated in and correctly predicted that a branch would soon form in the city. The CWCC continued to host NAACP speakers and meetings at Bethel A.M.E. Church and in September a local NAACP branch was officially admitted to the national association. Being that NAACP Branch #3053 grew out of the CWCC, Cable served as first branch president and its members and board were comprised entirely of women for the first year of operation. According to the branch’s website, the local chapter was organized to help the community “achieve equality and gain access to rights guaranteed under the Constitution of the United States.” Throughout its history, the branch fought for equal housing and employment opportunities, challenged discrimination through lawsuits, lobbied for legislative reform, and emphasized voting to effect change.

The branch held its early meetings wherever space was available, including and Willis Chapel, before operating on Indiana Avenue, 111 East 34th Street, 4155 Boulevard Place, and, as of 2020, at 300 East . The new chapter quickly got to work, investigating instances of discrimination at public playgrounds and women’s prisons. Indianapolis was the first city to respond to the NAACP’s request to send $100 for legal redress lawyers. This network of lawyers continues to be crucial to the organization, as local lawyers investigate reports of discrimination and serve as liaisons between individuals needing assistance and local legal organizations. Lectures on topics like the importance of organizing and “The New Abolitionism” drew prominent Black leaders, such as Attorney and Rev. W. L. Weaver, as well as white members, many of whom belonged to the Jewish faith, to the newly established branch.

In an atmosphere of heightened racial hostility of the 1920s, the Indianapolis school board proposed the construction of a separate public high school for the city’s Black students. In December 1922, the school board voted in favor of the proposal “despite vigorous protest by a large delegation of colored citizens,” who rightfully feared that a separate school would create logistical problems and result in inferior facilities and educational opportunities for Black children. The following year, Indianapolis citizen Archie Greathouse and NAACP Branch #3053 sued the school board to prevent school segregation. After this effort was defeated by the local courts, opened to Black students in the fall of 1927. The quality of faculty and educators made the school a symbol of pride for the city’s Black population.

In the mid-1920s, the infiltrated the city and state government and convinced the Indianapolis City Council to adopt a zoning ordinance that would prevent African Americans from buying homes or living in white neighborhoods. The Indianapolis NAACP chapter successfully challenged the constitutionality of the ordinance, although segregation and discrimination in public areas remained. According to the NAACP’s branch history, the Indianapolis chapter led efforts to stop the Klan’s influence in politics by organizing the Independent Voter’s League to vote Klan members out of office. Branch #3053 also hosted anti-lynching fundraisers to combat the group’s perpetration of hate crimes.

Chapter membership declined in the 1930s, as the country was in the throes of the Great Depression. However, the branch continued to fight employment discrimination by collaborating with the Citizen’s Employment League. World War II buoyed membership and in the 1940s Branch #3053 challenged the exclusion of African Americans from defense employment and segregation within the military. In a 1949 lawsuit against the Indianapolis Public School system, the NAACP branch and legal representative successfully abolished “the legal basis for segregated schools. Although the maintained segregation by reestablishing elementary school boundaries, the case laid the groundwork for full desegregation in Indianapolis and challenged school segregation five years before the U.S. landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. An NAACP committee continued to challenge the school board’s “sincerity” about implementing the desegregation law in 1951.

In the early 1960s, the chapter organized marches in support of President Kennedy’s legislative plan to end discriminatory practices and hosted workshops to inform residents about civil rights bills before the legislature. The branch also focused on police brutality, organizing protests, and later meeting with the mayor to discuss discrimination in the police department, which led to the appointment of the IPD’s first Black Inspector. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the chapter continued the fight to end segregation in Indianapolis’s public schools (See ). Its investigation helped convinced the U.S. Justice Department to file suit against IPS, which was found guilty of de jure segregation in 1971 (See ). While the chapter advocated two-way busing, NAACP members considered it a victory when Judge ordered the one-way busing of 6,000 inner-city students to six township schools in Marion County.

On the heels of the Black Power Movement of the 1970s, NAACP branches across the country, including Indianapolis, sought to demonstrate Black consumer power through boycotts of prejudiced businesses. Branch #3053 participated in the Fair Share Program and Black Dollar Days to encourage employers to hire African Americans and “remind merchants of the tremendous consumer power of Black Americans. However, by the early 1990s, the chapter came under criticism for being inactive and its plans to host the NAACP national convention in July 1993 were nearly revoked. That same year, fearing the 1971 desegregation order could be circumvented, the branch threatened another lawsuit against Indianapolis Public Schools to prevent it from implementing the Select Schools plan, which would allow parents to choose from a group of schools that their children could attend.

At the turn-of-the-21st -century, the local branch lobbied for federal and state hate crime bills and the Violence Against Women Act, citing police apathy to reported crimes. The branch continued to advocate for voting as a method to effect change, hosting Dignity Day to increase voter turnout, as well as a youth voting forum to educate young people about the political process. Branch #3053 also established the ACT-SO program, which paired underserved minority students with mentors to help them excel in sciences, arts, and humanities. In 2017, the chapter helped pass the Ethnic Studies Bill, which mandated all state high schools offer ethnic and racial studies as an elective course.

With the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Branch #3053 has prioritized criminal justice reform. The branch condemned the 2018 shooting of unarmed Black man Aaron Bailey, calling for legislative reform and dialogue with the city’s stakeholders regarding best practices for use of lethal force. Branch leaders also issued a guide on how parents can teach their children about racial profiling. Branch #3053 continues to work towards the mission of its founders, combating racial injustices and fighting to preserve the civil rights of Black residents.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.