Founded as the Team Drivers International Union in Detroit in January 1899 and chartered by the American Federation of Labor, the union initially represented unskilled wagon drivers and haulers. A Chicago-based splinter group, the Teamsters National Union (1902), merged with the Team Drivers in 1903 to become the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

The union, led by president Cornelius P. Shea (1903-1907), selected Indianapolis as its national headquarters because of the city’s central location and railroad connections. Maintaining its offices at 147 East Market Street until 1909, the Teamsters then occupied two floors of the Carpenters Union national headquarters at 222 East Michigan Street. Irish-born Daniel J. Tobin, who served as the Teamsters’ second president (1907-1952), resided in Indianapolis until his death in 1955.

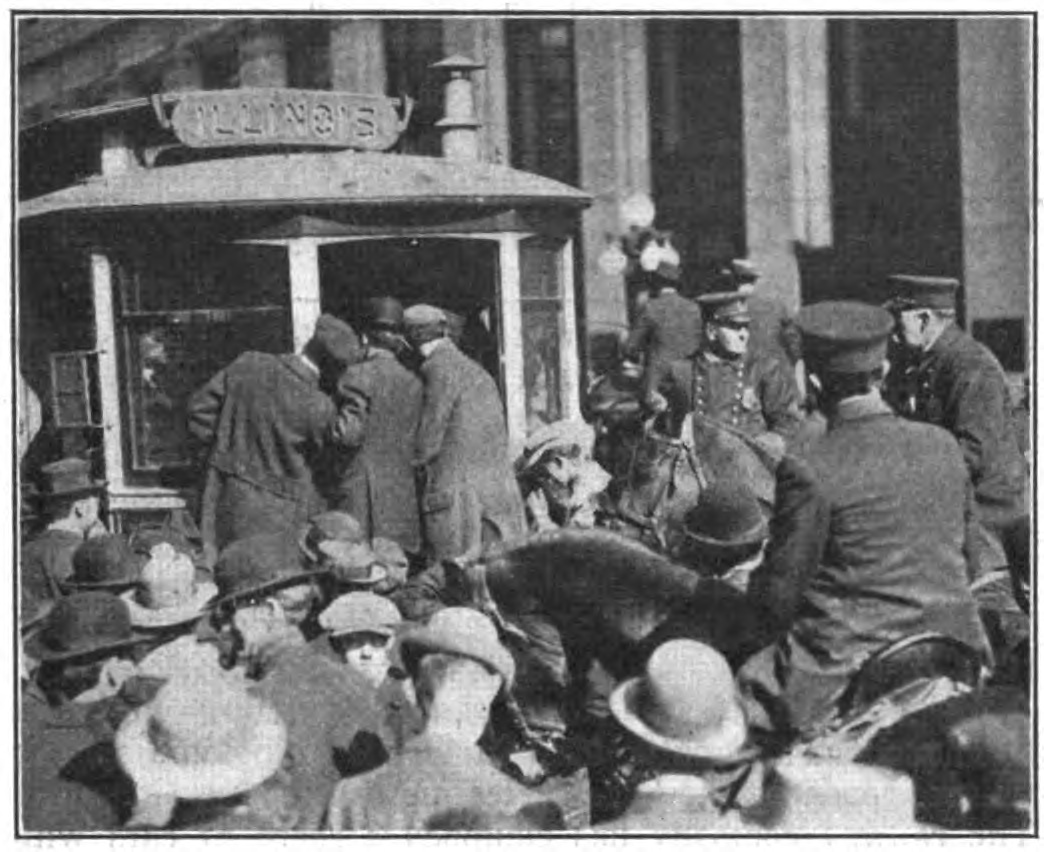

The first half-century of the American labor movement was marked by strikes and violence. Strikes by Teamsters in Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere caused community panic because urban populations relied on team drivers to deliver food, clothing, and other daily necessities. Riots and bloodshed often resulted, with casualties on both sides of the conflict. As union activity spread, it became common management practice to use organized crime thugs to break strikes. In defense and retaliation, big-city Teamsters, as well as other unions, often made alliances with local gangsters, which spawned the continuing involvement of organized crime in labor affairs.

Indianapolis experienced some degree of this violence. Following the of October 31-November 7, 1913, Teamsters Local No. 240 voted November 30 to strike over wages. Anticipating public disorder, Mayor reorganized the police department and issued proclamations against crowds exceeding three people. He dispatched police car patrols and deputized 250 business and professional men equipped with revolvers to protect the lives and property of citizens. Within a week, the special force numbered nearly 1,000. residents raised $500 to hire officers to patrol their neighborhood after one resident was attacked for breaking the strike. Vehicle owners of Indianapolis established the “Commercial Vehicle Protective Association” to protect their property and combat union activities by offering rewards for the arrest and conviction of the “lawless element”.

Although union officials urged strikers to avoid violence and criticized special officers for provoking street fighting, the public and the Employers’ Association (later the ), disturbed by the shattered peace, held the Teamsters responsible. By 1920, these forces had succeeded in reversing the course of unionization by defeating local labor-supported candidates, securing passage of anti-boycott and anti-picketing ordinances, and advocating state legislation for mediation and arbitration.

During the group’s years in Indianapolis, the Teamsters grew from a group of small union locals to the largest, wealthiest, and most powerful labor union in the country. For years, the union expanded gradually, organizing drivers, stablemen, and warehouse workers in major cities. Membership grew from approximately 60,000 nationwide in 1915 to 76,000 by 1924.

Growth mushroomed during the 1930s due, in part, to extended rights that labor derived from new federal legislation. But more directly, it was the result of innovative Teamsters activities in Minneapolis, conducted by Teamsters officer Farrell Dobbs and a militant group of Communists.

Dobbs was an avowed Trotskyite in the Socialist Workers Party, an American wing of the Communist Party that supported Leon Trotsky and opposed Joseph Stalin. Dobbs saw the labor movement as a vehicle for a Communist revolution in America. In 1934, he called a strike of all Teamsters in Minneapolis, seeking increased hourly wages for warehousemen and drivers. The strike was successful, following violent clashes and a declaration of martial law by the governor.

Seeking to expand his jurisdiction and power, Dobbs organized long-distance truck drivers, who were just beginning to compete with railroads for long freight hauls, and required that all drivers delivering to his unionized Minneapolis terminals be union members. He also organized freight terminal warehousemen in other cities, making the same requirements of drivers who delivered there. This tactic became a key strategic factor and a turning point in Teamsters’ growth. In the far west, Teamsters’ leader Dave Beck adopted Dobbs’ tactic, as did Jimmy Hoffa who later assumed control of Dobbs’ Minneapolis local. By 1939, the union’s membership had reached 420,000.

In Indianapolis, Teamsters’ president Tobin opposed Dobbs’ activities, preferring to concentrate on AFL affairs and Democratic politics rather than centralized Teamsters’ activities. Since this was a time when Communist activity in unions generated intense public pressure and government scrutiny, Tobin resisted Dobbs and his Trotskyites, causing Dobbs to leave the Teamsters in 1940 to work full-time on Socialist Workers Party activities. Tobin then purged the Trotskyites from the Minneapolis local in 1941.

Californian Dave Beck was elected Teamsters president upon Tobin’s retirement in 1952. The next year, when the Teamsters counted nearly 9,000 members locally and over one million nationally, Beck moved the national headquarters to Washington, D.C., to better serve the lobbying and legislative interests of the union.

The Teamsters continue to have a significant presence in Indianapolis and Central Indiana through its Local 135. With over 13,000 members, Local 135 is one of the strongest locals within the international union. While its main business offices are located in Indianapolis, Local 135 maintains regional offices in Bloomington, Columbus, Lafayette, Michigan City, Muncie, and Terre Haute.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.