Indianapolis residents are served by more than 200 parks and over 11,000 acres of greenspace, though original plan for the did not include any designated public green spaces. There seemed no need for parks since early residents had pastures, cemeteries, and undeveloped land all around them to use for recreational areas.

As the Civil War approached and the city experienced congestion for the first time, citizen action in favor of public parks began to build. In 1859, Timothy Fletcher donated a plot of land to the city with the provision that it be improved and used as a public park. The City Council, believing Fletcher’s gesture was a ruse to elevate the value of his adjacent land, refused his offer. Other private donations were also viewed with suspicion, and the council chose not to act upon them.

Using a different tactic, George Merritt was responsible for the first public park in Indianapolis. He repeatedly petitioned state and local authorities for the donation of state land to use as a public park. Governor finally offered the land now known as for use as a recreational area. By 1864, the City Council took over the management of Military Park as well as University Square and the Governor’s Circle.

By the 1870s, citizens became more vocal in their desire for public parks, and the City Council launched a tentative program of park purchases. In 1870, the city purchased the land that currently contains Brookside Park from the heirs of . Three years later, a group of northside residents petitioned the council for a park along , with seven citizens donating 91.5 acres.

The northside project failed to gain council support, but similar efforts by a group of southside residents ultimately led to the purchase of Southern Park, later renamed . Again the council did not develop this property, choosing instead to lease it to the Indiana Trotting Association. It was not until 1876 that the city turned the land into a park, making Southern Park the first city-owned park in Indianapolis.

By the 1880s, residents privately and in combination with the city improved all these parklands. Merritt funded Military Park’s original improvements and subsequently installed a playground. University Square was voluntarily landscaped by neighbors of the park, and a statue of Vice President Schuyler Colfax was erected there as a gift from the Odd Fellows of Indiana. Citizens planted trees in Garfield Park and carried out other improvements funded by the council. Additionally, residents in the area of St. Clair Square created their own park, collecting subscriptions, laying walks, and planting trees.

These 19th -century public parks were intended as passive recreational areas, where middle-class and wealthy citizens could relax and enjoy nature. It was not until 1895 that the City Council, under a new (1891), created a commission to develop a system of public parks in Indianapolis. The Commercial Club, the forerunner of the , drafted the legislation creating the five-member Board of Park Commissioners to administer the six previously established parks.

City officials consulted with nationally prominent park landscape designers to guide park development. The Commercial Club hired parks consultant Joseph Earnshaw in 1894, who recommended that sites be purchased and developed along and , connected by a chain of small parks and interconnecting parkways.

Once established, the park board conducted a survey of possible park sites and commissioned John C. Olmsted, stepson of famed landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., to develop a plan for future parks. The Olmsted plan, like the Earnshaw plan, recommended that local waterways be the focus of a system that would include small parks, boulevards, several larger local parks, and a large public reservation.

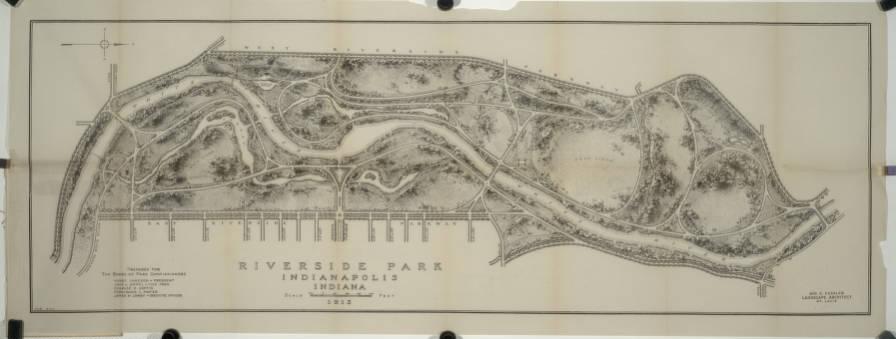

Mayor , who assumed office in 1895, was a strong supporter of parks and was instrumental in laying the foundations of the park system. At his behest, the council approved a limited version of the Olmsted plan and authorized the purchase of over 1,100 acres of land, including much of what is now Riverside Park, during the early 1900s.

Much of the land bought at this time had previously been used as unauthorized dumping grounds. The parks department saw its job as ridding the city of unclean and unhealthy areas as well as providing beautiful recreational spaces. Park improvements included landscaping, building water features, and adding walking paths and benches, with the bulk of the work focusing on Riverside and Garfield parks. Parks also began to provide entertainment such as the 18-hole golf course, the zoo, and steamboat cruises on the White River at Riverside Park.

In 1908, the park board hired nationally known park planner as a consulting landscape architect, ushering in an era of greater park presence throughout the city. Kessler’s plans consisted of lining the city’s streams with boulevards that would link major parks. This resulted in the White River, Fall Creek, and Pleasant Run parkways. Kessler also laid out the scenic, tree-lined boulevard through Washington and Wayne townships.

Kessler helped pass a new park law in 1909 which allowed the department to levy taxes for park purchases and improvements. The law sparked much public debate. Not all citizens agreed that public parks should be a municipal responsibility. Successive park laws in 1913 and 1919, however, further increased the department’s autonomy and taxing power. The new legislation made possible department expansion, the purchase of new properties, and the beginnings of boulevard construction.

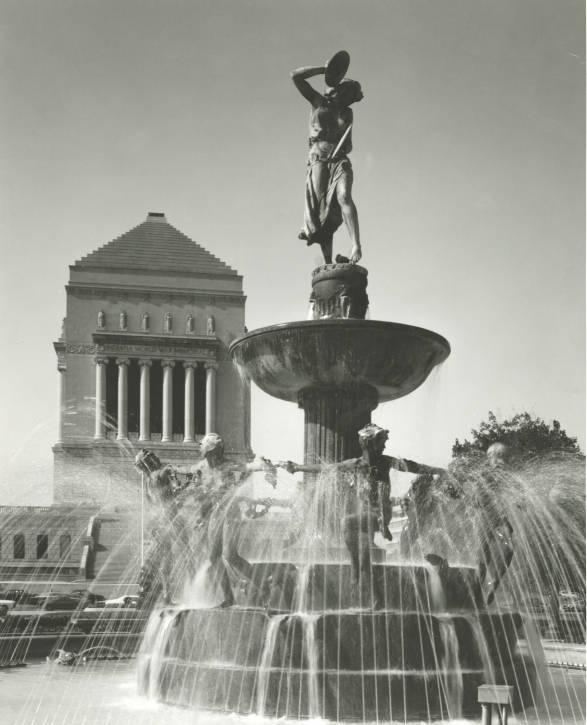

Despite the city’s official sponsorship, citizens continued to actively support park development during the early 1900s by donating property or funding park improvements. The bequests of Alfred Burdsal and George Rhodius in 1911 funded the purchase and development of Willard Park, Burdsal Parkway, and Rhodius Park. Other citizens financed memorials placed on park property, such as the Depew Memorial Fountain and the and statues.

During World War I, the city suspended most park activities and funding. As a result, almost all park contracts and improvements were discontinued except for those completed by a specially formed Park Construction Force. Simultaneously, the department supported the war effort by opening park property for use as vegetable gardens to help alleviate general food shortages.

The department resumed park purchases and expansions in the 1920s. As a result, the park system grew to include 24 parks and parkways with land totaling approximately 1,900 acres. This acreage included the three large parks outside the downtown area: Riverside to the northwest, Garfield to the south, and Brookside to the northeast. The parks also gained several structures and gardens that were donated and dedicated to Marion County soldiers and veterans.

The idea that public parks should provide both active and passive recreation originally surfaced before the war, but recreational programming did not become a high priority until later. As early as 1910, the park board joined with public school and library officials to provide recreational programs, gradually accepting more of this responsibility.

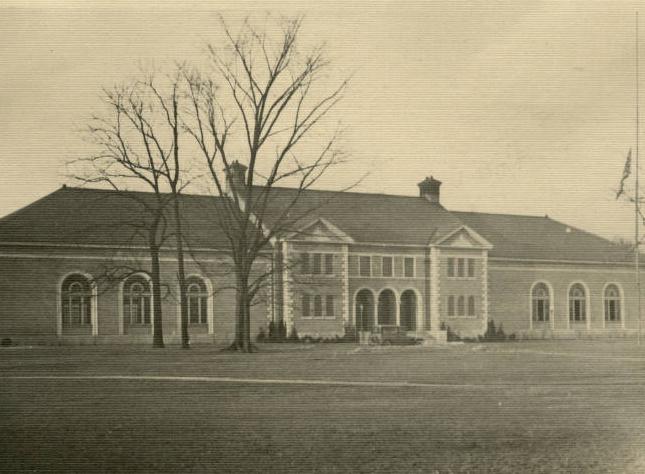

In 1919, a new park law transferred the recreation division from the city’s public health department to the public parks department, which began constructing a system of playgrounds, pools, and community recreational centers in the parks. Parks soon provided a variety of year-round athletic programming, classes, clubs, and special events. The centers also provided bathing facilities, day nurseries, dental clinics, and served as a neighborhood headquarters for welfare agencies.

Although some residents opposed the expanded definition of public parks, these new activities proved successful, greatly multiplying park attendance. This programming also expanded the department’s presence within the city, establishing close links with other community groups such as the school board, Southside , settlement houses, , and the .

During the 1930s, the system of neighborhood parks, playgrounds, boulevards, and recreational areas in Indianapolis grew despite the Great Depression. The department, however, began to charge fees for some of its operations, such as golf courses, swimming pools, and community houses, to make them self-sustaining.

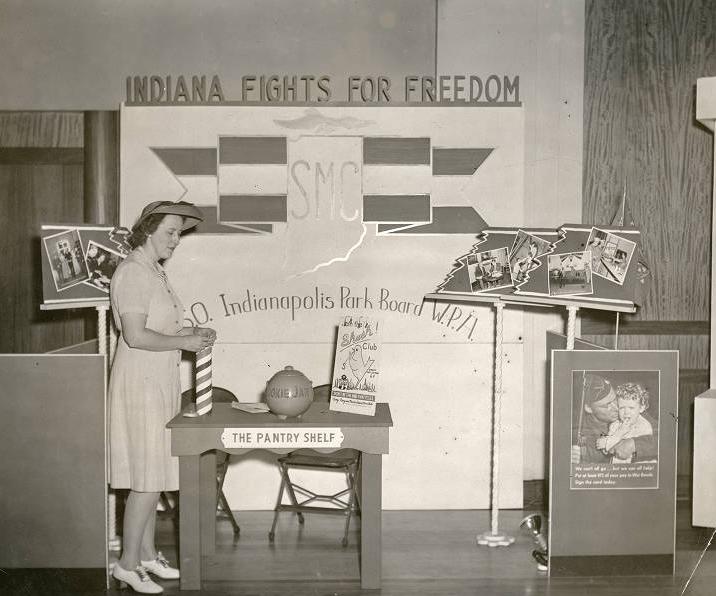

At the same time, volunteers from women’s groups, civic organizations, and WPA and CWA workers augmented the parks’ workforce. Park activities focused on city beautification projects and year-round recreational activities–completing Lake Sullivan, constructing wading pools, staffing summer playgrounds, landscaping the boulevards and public properties, and sponsoring dances. Park community houses became popular, low-cost centers of activity during the 1930s, housing many clubs and classes as well as providing space for other groups.

Despite the expansion of park facilities and programs, a study in 1937 found that only 20 percent of public park acreage was within a two-mile radius of half of the residential population.

The parks department’s major strategies for land acquisition had been to receive donations or purchase cheap land on the outskirts of town. The policy of buying small parcels of land within walking distance of all residents throughout the city remained largely unimplemented by the 1940s. Additionally, the African American population was particularly ignored because of the department’s segregation policies.

The World War II years added temporary new responsibilities for the public parks—running canteens and clubs for servicemen and providing land for postwar veteran and emergency housing. After the war and into the 1950s, however, the parks department again turned its attention to recreation and city beautification.

By the late 1940s, the city renewed its efforts to beautify and restore its 52 parks, many of which had not had significant improvements for at least 20 years. Large bond issues in the early 1950s helped pay for this renovation work. The playground system was also expanded, and parks continued to sponsor a growing number of clubs, classes, and “teen canteens.” Although the parks had long hosted festivals, the 1950s saw an increase in music festivals, carnivals, and dances, many of which were revenue-producing projects.

Athletics became increasingly important after the 1940s, and the parks provided the sites for many boxing, basketball, and baseball leagues and tournaments, including some of national significance. In one instance, the purchase of in 1946 with its Olympic-size pool led to the U.S. Olympic swimming trials in 1952 and the national championship swimming meet in 1958. Golfing also became a high priority during these years, with the parks department even hiring professionals to assist patrons and oversee the courses.

Rising rates of suburbanization and competition with private sources of recreation during the 1960s forced park officials to change the focus of public parks. Downtown properties increasingly received less attention as the parks department devoted resources to parks nearer the suburbs and purchased parkland in suburban townships. Financed by Indianapolis and Marion County taxes, the parks department purchased Northwestway, Northeastway (now Sahm Park), Southeastway, and .

Not all downtown efforts were forsaken, however, as the department began what would become a perennial effort at park promotion by encouraging neighborhoods, clubs, and civic groups to “adopt” and help maintain a park. In addition, Washington Park became the site of a new city zoo in 1964.

Changes continued during the 1970s. Unigov expanded the Indianapolis service boundaries to include all of Marion County and created a reorganized . Citizen interest in parks fell as suburbanization and park vandalism increased. Public parks also competed for space and resources with urban expansion and renewal efforts. The parks department responded by experimenting with new programs and projects.

Using millions of dollars from federal grants and local bond issues, it constructed a system of small parks known as “tot lots” and “vest pocket” parks along highways, refurbished deteriorating facilities, built new facilities, expanded recreational programs, and made extensive improvements to Eagle Creek Park (which opened in 1974). The parks department also renamed many downtown parks after notable local and national African Americans, reflecting the error of its earlier segregationist policies and the changing nature of park visitors.

While these efforts resulted in notable successes, such as the institution of the , a general lack of park usage, inadequate maintenance, and vandalism became serious problems, especially for downtown parks. Several park officials were prosecuted for mismanagement and fraud, further lowering the public’s confidence. Parks on the outer edges of the city, however, offered first-rate facilities and programs, especially Eagle Creek Park.

A new parks administration began a greater focus on amateur sports during the 1980s, which inspired a resurgence in park usage and image. The department, in an effort to supply a unique recreational need in the community, began to phase out smaller downtown parks in favor of large natural-setting parks and linear parks equipped with fitness and bike paths. Eagle Creek became the showcase of the park system, offering a lake, nature trails, and many recreational facilities. Large bond issues funded amateur sports facilities, such as the Lake Sullivan Sports Complex and the Major Taylor Velodrome, which along with the 11 golf courses became venues for special events as well as local and national competitions. The also relocated from Washington Park in 1986 to the new .

The 1990s and early 2000s were marked by numerous expansions to Indianapolis parks and greenspaces. The park system of the early 1990s had 73 properties, 16 community recreation centers, 13 pools, and 12 golf courses over 9,657 acres. Most of these properties were located in Center Township but continued to compete for space with other governmental agencies.

The parks offered a wide variety of traditional recreational and nature programs, including “Tox-Away Day,” recycling centers, and urban forestry programs. Segments of the community were committed to the city’s parks as is evidenced by the 1991 organization of the Indianapolis Parks Foundation, a private citizen funding group, and the use of neighborhood advisory councils in park planning.

The Office of Land Stewardship was founded in 1992 to manage the many natural areas in the parks and greenways of Indianapolis in partnership with the parks department. By the 2000s, this office managed about 2,000 acres of land across 37 park properties and multiple city rain gardens. The group also worked on programs to preserve critical wildlife habitats and provide passive recreational opportunities.

An important focus for the parks department in the mid-1990s became the development of the “Indianapolis Greenways Project.” In an undertaking built upon Kessler’s acquisition of waterway corridors, department officials and city planners looked to develop approximately 155 miles of recreation and fitness trails along local waterways and abandoned railroad rights-of-way.

One of the trails in this project was The , which had its first 10 miles completed in 1999. This railway-turned-trail connected Indianapolis residents via its scenic greenway from 10th Street downtown all the way through Carmel and Westfield to the north of the city. By 2013, the Indianapolis Greenways Project had completed 60 of 155 miles of trails.

In addition to the greenways project, the parks department worked to gain more land to use for public recreation. This was achieved through long-term leases, advocacy for land donations from land developers, donations as a result of rezoning negotiations. These approaches led to several additions like the Town Run Trail Park, The Frank and Judy O’Bannon Soccer Fields, and the Little Buck Creek Greenway.

Throughout the early 2000s, the parks department entered into multiple partnerships, continuing its work to expand existing park properties. With the help of the Indianapolis Parks Foundation, Southwestway Park gained 187 acres, and Pogues Run Detention Basin gained 43 acres for public use through a partnership with the Department of Public Works in 2003.

From 2000 to 2014, the parks department oversaw 49 expansions and acquisitions to parks, trails, and other recreational centers. It was during this period that the city finally broke ground for the after several years of planning. The trail was developed as an 8-mile addition to the city’s greenway system and served to connect the six of Indianapolis

The Indianapolis Parks Foundation began Indy Urban Acres in 2011 as a new sort of public greenspace. Using undeveloped property owned by the parks department, an 8-acre urban farm was created to provide access to free produce as well as educate the Indianapolis community.

As of 2020, Indianapolis had 212 parks, 11,258 acres of green space, 129 playgrounds, 155 sports fields, 153 miles of trails, 23 recreation and nature centers, 19 aquatic centers, 21 spray grounds, 13 golf courses, and 4 dog parks. Despite this, Indianapolis still suffers from a shortage of easily accessible parks with only 32 percent of residents living within 10 minutes of a park. The national average is much higher at 70 percent.

In the Indy Parks and Recreation master plan for 2016-2021, the parks department outlined a strategy to remedy this by acquiring enough land to reach 12 acres per 1,000 residents.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.