Occasioned by a streetcar strike, the mutiny was the most serious breach of police protocol and one of the greatest breakdowns in public order ever seen in Indianapolis (see ). The Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees, attempting to organize the 900 workers of the Indianapolis Traction and Terminal Company, called for a strike of motormen and conductors on October 31, 1913. Determined to continue operations, the company dismissed union men and summoned 300 professional strikebreakers (“sluggers” and Pinkertons) from Chicago.

Saturday morning service was near normal, but throughout the day more crews joined the strike or fled their posts. Unruly crowds stoned and wrecked six trolley cars, cut overhead trolley wires, and frightened passengers away. A police squad protecting repair crews met a hail of brickbats and stones, forcing its retreat. The strike disrupted the interurban system that connected Indianapolis with many communities in the state. When the afternoon train carrying the strikebreakers arrived at , police cleared a passage through a large, hostile crowd to strikebreakers’ headquarters in the Louisiana Street car barns, but, for the most part, the police refused to interfere.

On Saturday afternoon, Mayor told Governor Samuel M. Ralston that order could not be restored without the state’s intervention. He also asked the Marion County sheriff to deputize 200 men to aid police, but the sheriff refused, claiming he lacked authority.

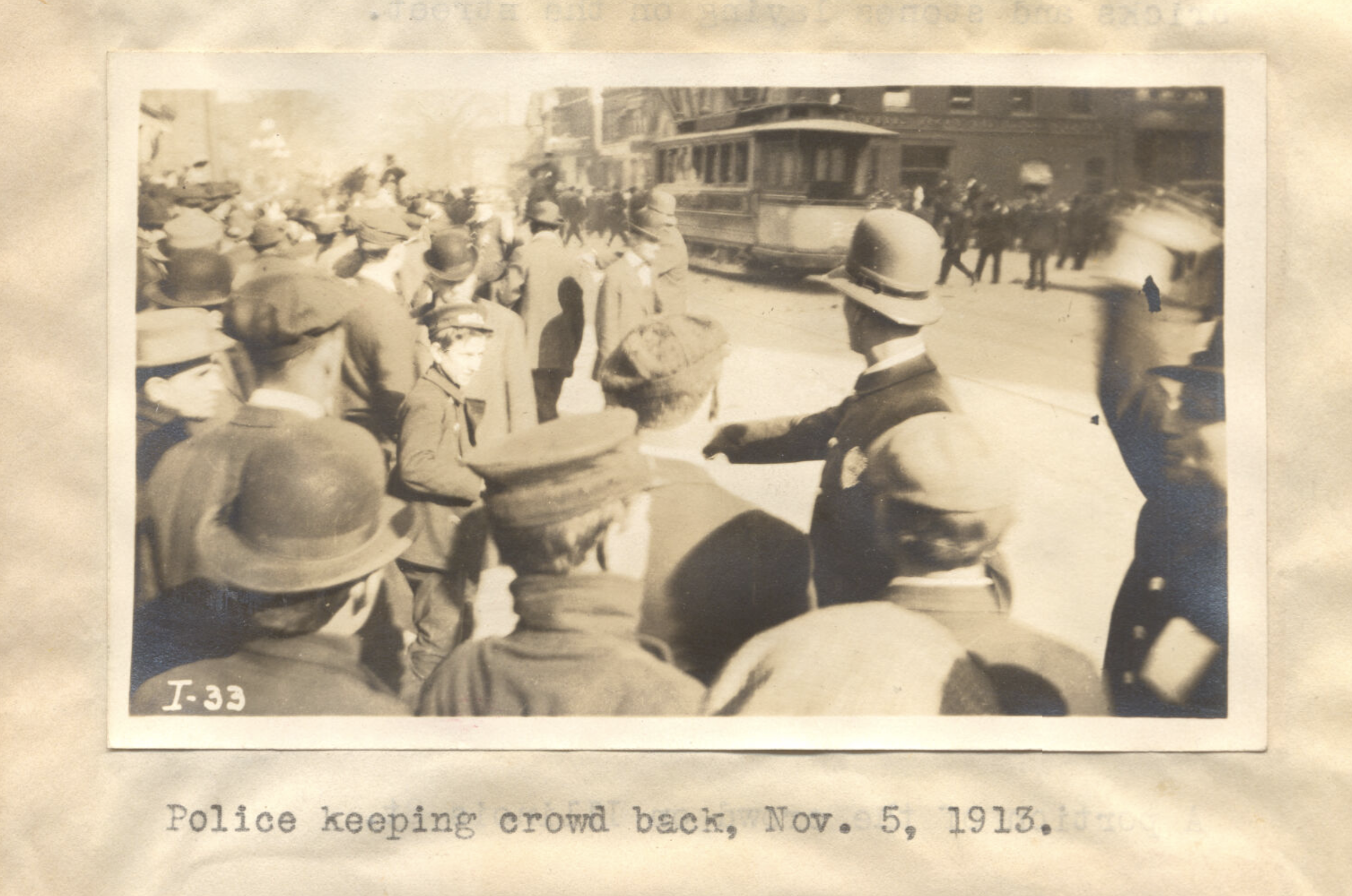

The issue that led to the mutiny of 33 policemen was the traction company’s demand that police ride the cars to protect the strikebreakers. Among the 200 patrolmen were many former craftsmen and workingmen. Only 20 arrests were made the first day, and there were reports of police standing by while crews were intimidated and cars vandalized. On Sunday, a patrolman resigned rather than ride the cars as ordered.

Shank, who witnessed the scene, supported the officer’s action and pledged to defend him in any future hearing, a statement that was widely reported. On Tuesday, Chief Martin Hyland again ordered police to ride the cars, but 29 turned in their badges rather than do so. Short of men and fearing the complete disintegration of the force, Hyland did not accept their resignations; he placed them in other duties, promising to charge them with insubordination later.

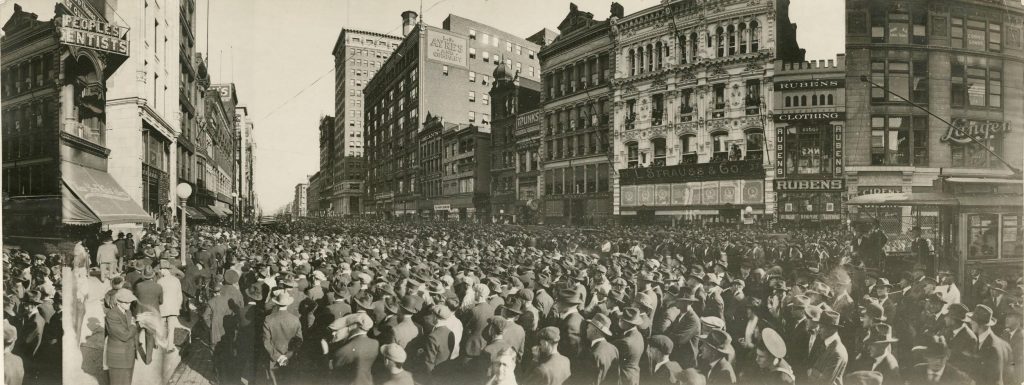

The worst affray took place Wednesday when rioters in a crowd of 8,000 wrecked a car on Illinois Street. Thirty were injured, among which seven strikebreakers and two policemen were seriously wounded. A day later, Governor Ralston quietly assembled 2,000 guardsmen at armories and in the basement of the State House. On Friday, the traction company bowed to public opinion and pressure from Ralston by accepting arbitration via the Public Service Commission. Within three hours, the strikebreakers were on a train to Chicago. By the next day, trolley service resumed.

On November 12, Hyland charged 33 officers with insubordination. When the public safety board suspended the accused on November 13, there was talk among police of a general walkout. At the trial (with the board acting as a court), Mayor Shank supported the men: to ride the cars would have dangerously worsened matters. All but one of the men claimed they had been asked to volunteer or argued the mayor’s policy superseded the chief’s orders. All acknowledged a refusal to ride with strikebreakers.

Petitions condemning the officers came from business organizations; petitions in support, one with 4,000 signatures, came from labor. The board voted 2 to 1 for acquittal; Hyland, a 29-year veteran, then resigned, as did the minority board member. With labor troubles impending among the teamsters of the city, angry businessmen called on Shank to resign or face impeachment. To head off the latter, the mayor promised to resign if the teamsters struck. When his mediation efforts failed to prevent a strike, Shank resigned on November 28, barely a month before the end of his term.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.