In the summer of 1877, the nation experienced the most serious labor disruptions in its history. On July 16 a spontaneous labor uprising against the at Martinsburg, West Virginia, spread in a few days to paralyze nearly every railroad center from Baltimore to St. Louis. A coordinated policy of wage cuts, along with other grievances, set off the strike, and in the beginning, the public sided with the workers. When the strike reached Indianapolis on Monday, July 23, great destruction of property and loss of lives had already occurred in other states.

Mayor and the city’s strike leader, Warren H. Sayre, secretary of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, shared horror at the events that had taken place elsewhere. Sayre assured Caven that his men were law-abiding and would not use force. In light of this promise, Caven met with railroad officials and swore in 200 railroad employees as special deputies to protect railroad property.

At the Union Depot, well-organized and disciplined strikers spoke to the crews of arriving trains, and passenger and freight cars, guarded by conductors and porters, piled up on the sidings. Although noting the peaceable strikers, Caven convened a citizens’ meeting before the courthouse the evening of July 24, the strike’s second day, to enroll a militia under a committee of public safety to act with the mayor and the sheriff. The results, however, were disappointing; only a hundred men enlisted the following day.

The strike brought the economy of the city to a near standstill: wholesale merchants did little business, the closed, and many other factories shut down. The community was divided between sympathizers who hoped that local railroad officials would offer a compromise and strike opponents who believed that the strikers were a mob that threatened people’s rights.

, a federal judge for the District of Indiana, took the latter view. He placed the railroads in receivership, then under his jurisdiction, and authorized the U.S. marshal to arrest strikers interfering with the movement of the trains. He also called for the establishment of a militia, commanded by business and professional leaders, to break the strike and end the embargo at the depot.

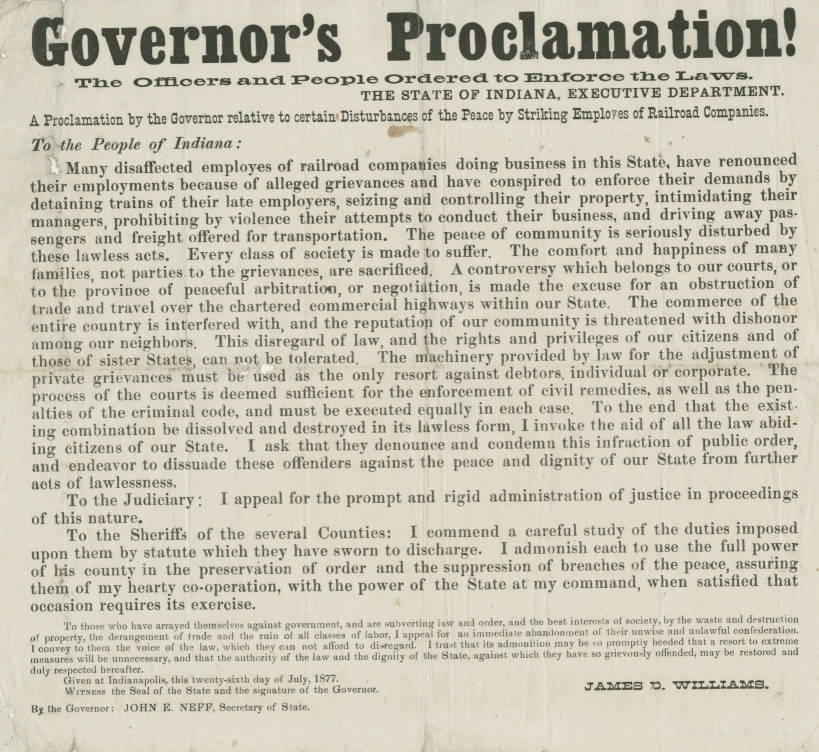

On Thursday, July 26, with the support of future U.S. president , former governor Conrad Baker, former mayor , and other notables, Gresham forced a merger with Caven’s committee of public safety in which Gresham and four others held five of the seven leadership posts. and Macauley was named brigadier general of the so-named Indiana Legion.

Gresham’s group held complete control of the city’s military forces. The city council on Friday approved a Gresham resolution that empowered the committee to take any further steps it deemed essential. By week’s end, the city held 271 regular army troops, at least 750 more under Macauley, 72 Montgomery Guards under Hoosier soldier and author , and others—in all at least 1,100 men-at-arms and perhaps twice that number. Police, sheriff’s deputies, and deputized strikers totaled another 400 to 600. In a city of 67,000, then, perhaps one of every four adult males was responsible for protecting the city and available to put down riots. Indianapolis had become an armed camp.

In fact, the strike had ended Friday evening. All but two companies of the Indiana Legion were mustered out Saturday and the mayor reiterated his statement of the previous day that no impediment existed in Indianapolis to the movement of trains.

Only employees of the Bee Line Railroad won rescission of the 20-percent pay cut and the promise of regular paydays. Other strikers lost their jobs or returned on their employers’ terms. Judge Gresham outraged the mayor by bringing Sayre and 14 others to trial, with all but Sayre and one other striker convicted and sentenced to terms ranging from 30 days to 6 months.

The Gresham committee of public safety wanted the voluntary legion to be made permanent, available to suppress mobs at their “first outbreak,” but the circumstances hardly warranted it. At a time when 53 died at Pittsburgh, 18 at Chicago, and 11 at Baltimore, the only casualty in Indianapolis was a militiaman whose foot was stepped on by a horse. The city remained peaceful and orderly during the Great Railroad Strike because of the determination of the strikers to avoid bloodshed and the near unanimity of the city’s elite which united itself against the strike however peacefully conducted.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.