The National Federation of Miners and Mine Laborers was founded in Indianapolis in 1885. In January 1890 and now known as the National Progressive Union, it merged with local assemblies, to form the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA).

The UMWA became the official representative of coal miners across the country on January 25, 1890, when it received an industrial charter from the American Federation of Labor. The UMWA selected Indianapolis for its national headquarters in 1898 because of its central location near the coal-mining regions.

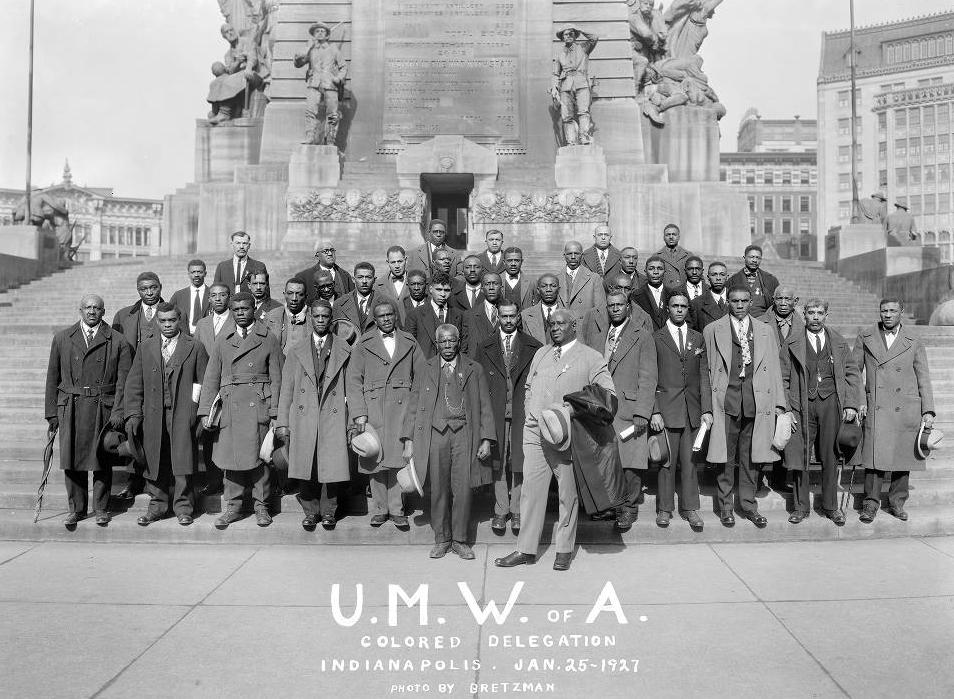

The union held its annual conventions here until 1934, enabling the city to witness the inner workings of the UMWA firsthand. These conventions were extremely important: delegates decided upon how to best deal with coal operators, engaged in numerous intra-and inter-organizational debates, and formed a unique organizational structure that allowed the UMWA to prosper.

Although wage increases were its foremost concern, the UMWA was also instrumental in abolishing the “company store” maintained by coal-mining companies. Company stores were often abusive, charging high prices and funneling workers’ income back to company owners. The UMWA also was involved in prohibiting work for boys under 16. Furthermore, it generated great union experience and loyalty that workers carried to other industries after coal mining began to decline in the 1920s.

The UMWA gained notoriety and additional members as a result of its successful 1896-1897 prosecution of a strike against operators in the Central Competitive Field, comprised of Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and western Pennsylvania. The UMWA’s efforts resulted in a standard wage rate and an eight-hour day for miners in this region. Indianapolis also witnessed the unfolding of the famous anthracite strike of 1902, in which the UMWA delegates and operators met in Indianapolis several times before President Theodore Roosevelt ordered both sides to a meeting at the White House where operators agreed to higher wages, ending the strike.

The , the Stevenson Building, and were the sites of many volatile encounters between the union and mine operators. At its 1906 convention, the UMWA prepared to strike. It demanded, as it had in 1902, that operators allow the southwestern states (Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Indian Territory [later Oklahoma], and Kansas) to join the Central Competitive Field, enabling the UMWA to negotiate one contract with a 12.5 percent increase in wages plus seven other demands.

President Roosevelt intervened again and arranged a meeting at the Claypool Hotel. The operators offered to raise wages, the UMWA dropped its other demands, and the strike was averted. In the course of these negotiations, Intra organizational debates raged among miners. The UMWA’s rival, Western Federation of Miners, citing the excluded Colorado miners, accused UMWA president John Mitchell of selling out.

Under Mitchell’s leadership, the UMWA developed its system of voluntary arbitration. Made up of both miners and operators, a scale committee met in Indianapolis annually to negotiate terms for the following year. By doing so, the UMWA avoided confrontations with operators while simultaneously securing better wages and working conditions.

Under the leadership of John L. Lewis (1919-1960), who maintained the union’s offices on the 11th floor of the , tension-filled conventions abounded in the 1920s. Lewis’ rigid style encouraged factionalism and, combined with a coal surplus and the Great Depression of the 1930s, resulted in a dramatic decline in membership, from a high of 500,000 during World War I to 100,000 by the end of the 1920s.

With little fanfare, the national headquarters of the UMWA moved from Indianapolis to Washington, D.C., in 1934, thus ending the city’s ties to the influential union.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.