From September 1918 to the late spring of 1919, Indianapolis suffered from a viral influenza pandemic that killed nearly 1,000 residents of the city in three months. First reported in the United States at Fort Riley, Kansas, in spring 1918, the worldwide influenza outbreak killed an estimated 675,000 to 850,000 Americans before it ran its course in the early summer of 1919, just over 10 times the number of Americans who died in World War I. The pandemic was Indianapolis’ worst public health crisis of the 20th century.

More than 43,000 U.S. soldiers, sailors, and marines died of the flu in 1918 and 1919. Half of the U.S. soldiers who died in Europe succumbed to influenza rather than combat. The disease had first manifested itself in the trenches of Europe and the Middle East in fall 1917, but since the combatants kept such a tight lid on news emanating from their fighting forces, the media dubbed it the Spanish Flu when it showed up in neutral Spain.

Epidemiologists later would determine that the pandemic first appeared in the Hoosier state in mid-to-late September 1918 in the Calumet Region adjacent to Chicago and then moved south across the state in two successive waves during 1918 and 1919. Rail lines at the time crisscrossed the state, and Indianapolis was the hub of an electric rail system that shuttled passengers on a near hourly basis to Chicago, Louisville, Ft. Wayne, Richmond, Evansville, and all points in between. An estimated 10,000 salesmen boarded interurban trains at the city’s on West Market Street every Monday morning, bound for a week’s calls across the state and the region.

Rail transportation provided a perfect vector for transmission of the pandemic in fall 1918. A September 27 Indianapolis Board of Health warning found the staff at General Hospital No. 25 at , located nine miles northeast of the city, coping with about 60 cases of influenza. In the city itself, a reported 200 residents were sick with the flu on October 1, and four were already dead. A week later, the number of new cases had spiked six-fold, to 1,200. On October 2, the Indianapolis Board of Health essentially shut down all public gatherings in the city.

Schools closed that Wednesday for the first time since a diphtheria epidemic in 1910 had swept the city, and all theaters, skating rinks, and other places of entertainment were shuttered. In the first week of October, there were 40 civilian deaths and 80 military deaths attributed to the flu and the inevitable cases of pneumonia that accompanied the epidemic.

The week of October 13 saw nearly 110 civilians and 70 military personnel succumb to the flu. Deaths spiked in the civilian community the week of October 20 when almost 150 residents died. Unlike typical cases of influenza, the 1918 variety was particularly virulent among young people. The death rate was highest among those between 15 and 39 years of age. Victims would often awake in the morning with a cough or sore throat, be bedridden by nightfall, and die of respiratory failure the next day. Because so many of the city’s young men had left Indianapolis for military training and duty, there was an almost daily litany of obituaries of local soldiers and sailors who had died at their army fort or naval base.

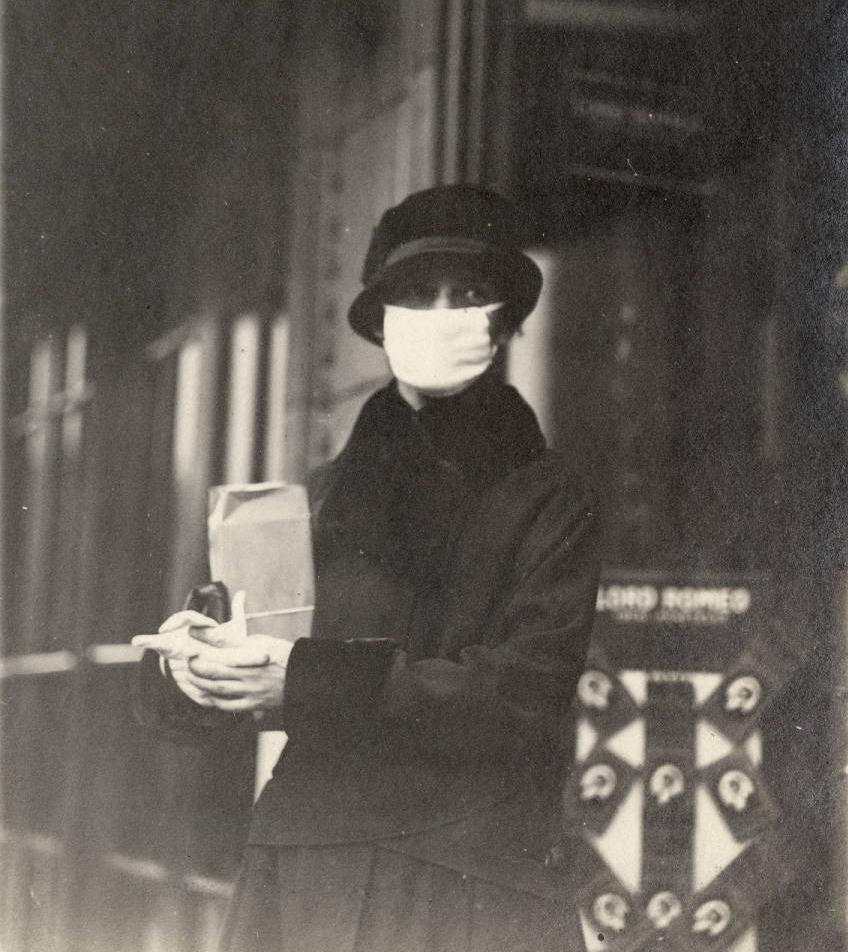

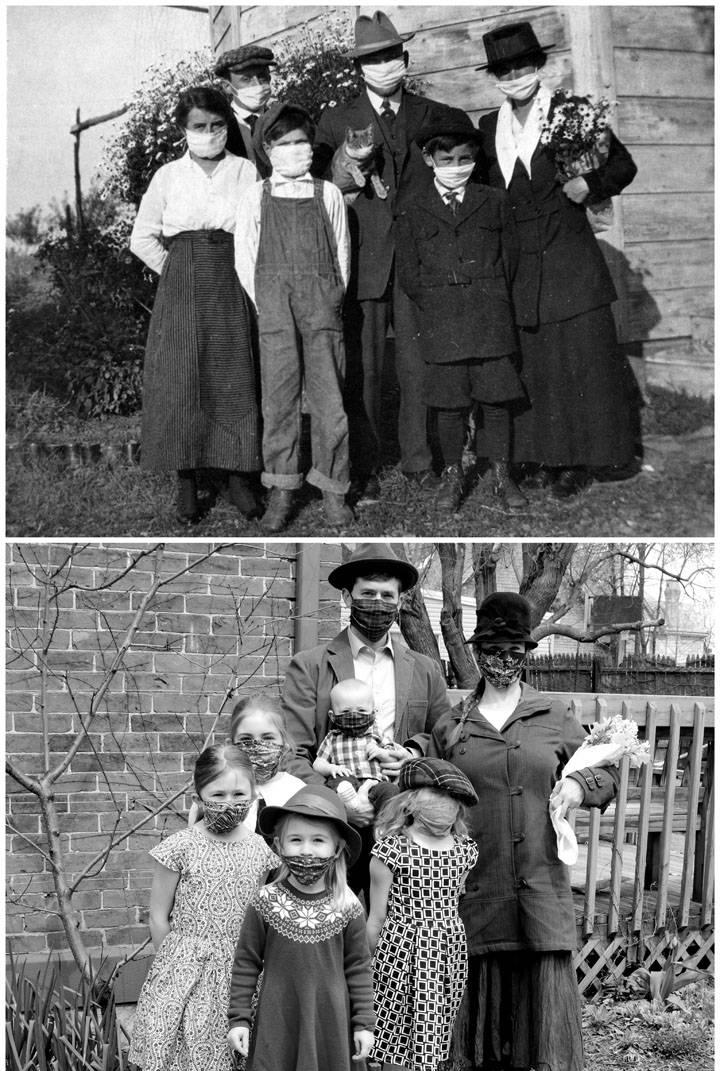

The city was fortunate with the presence of Dr. Herman G. Morgan, secretary of the Indianapolis Public Health Board for 35 years. First appointed in 1911 by Mayor , Morgan was inducted into the U.S. Public Health Service in 1917 and appointed to serve at Fort Benjamin Harrison. He retained his position with the city, and in 1918 had a unique perspective on the transmission of the deadly disease. It was upon Morgan’s assistance that the Board of Public Health shut down public meetings and ordered the wearing of cloth masks in October, measures which very likely helped Indianapolis avoid some of the worst effects of the pandemic. On October 17, the Board of Public Health extended the ban on meetings and gatherings until October 26. The ban was extended again to October 30, and city schools did not reopen until November 4. Cases declined throughout that week until November 11, when residents of the city, along with millions of other Americans, rushed into the streets to celebrate the armistice ending World War I.

By the weekend, Indianapolis was in the midst of the second wave of infections, with more than 110 new cases reported on both Thursday and Friday. The Board of Public Health quickly reimposed restrictions on meetings, shut public schools, and ordered residents to wear masks. The timely action resulted in a decrease in deaths due to flu. There were 306 influenza-pneumonia deaths in November in Indianapolis, down 29 percent from the October totals. As it was, Indianapolis did not report its first “fluless” day until December 16. By the first of the year, the pandemic had essentially run its course in the Circle City, but outbreaks in Louisville and Cincinnati in December and January spilled over into communities in southern and southeastern Indiana.

There were still 70 deaths in Muncie in March, but a strict 14-day quarantine policy applied to the more than 2 million U.S. soldiers, sailors, and marines returning from duty in Europe, coupled with partial herd immunity in the U.S., contributed to a wind-down in cases. By the advent of the 1919 flu season in the fall, Indianapolis newspapers contained far more advertisements for flu remedies than news of any resurgence of cases. In the end, Indianapolis had an epidemic death rate of 290 per 100,000 people, one of the lowest in the nation.

FURTHER READING

- Jaffe, Celeste H. “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in Indianapolis in 1918: A Study of Civic and Community Responses.” Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, 1994. https://hdl.handle.net/1805/4968.

- Simins, Jill Weiss. “War, Plague, and Courage: Spanish Influenza at Fort Benjamin Harrison & Indianapolis.” Untold Indiana, July 11, 2017. https://blog.history.in.gov/war-plague-and-courage-spanish-influenza-at-fort-benjamin-harrison-indianapolis/.

- Thomas-Fennelly, Adam. “Reflections and Remedies: The 1918 Influenza Outbreak in Indiana.” Untold Indiana, October 18, 2023. https://blog.history.in.gov/reflections-and-remedies-the-1918-influenza-outbreak-in-indiana/.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Beck, W. (2021). 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Jan 31, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/1918-spanish-flu-pandemic/.

MLA:

Beck, William. “1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/1918-spanish-flu-pandemic/. Accessed 31 Jan 2026.

Chicago:

Beck, William. “1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Jan 31, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/1918-spanish-flu-pandemic/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.