Residents of early Indianapolis prided themselves on the orderliness of the community. The peace was kept with a town marshal, the sheriff ( being the first) and a few deputies, a volunteer night watch, and a handful of constables and justices of the peace. But with the growth of population and the rise of nativist fears at the influx of Irish and German immigrants, the coming of the railroad, and the deep split over the liquor question, the 1840s and 1850s produced a perception that Indianapolis was in the grip of a crime wave.

The Early Professional Police Department, 1854-1890

Attempts in 1854 and 1856 to establish a paid city police force under an 1852 state law proved temporary, and the department was twice disbanded. In May 1857, the city council finally succeeded in creating a permanent Indianapolis Police Department (IPD). Paid $1.50 a day, a worker’s wage, a man patrolled each of the seven wards from evening to early morning, his only badge of office a silver star. A “watch captain” (“chief of police” in 1861) mustered the force daily and reported the number of arrests to the council.

In July 1862, the police received uniforms—a dark blue coat, light blue trousers with a cord along the seam, and a blue cap. The force, which doubled to 14 in 1861, the first year of the Civil War, grew to 47 by the war’s end, with a chief, two lieutenants, a detective branch, and patrolmen divided into day and night shifts in the nine wards. By 1876, the police force added six African American police officers to its ranks, though they were segregated, served in lower positions, and for almost a century lacked the right to arrest white criminal suspects. Ten years later, Benjamin Thorton became the first African American detective for IPD.

In the late 1800s, IPD, like its counterparts elsewhere, sought measures, equipment, and new technologies to increase its ability to combat crime. In 1883, the department procured two horse-drawn carts as an alternative to commandeering private wagons or conveying drunks to the station in a wheelbarrow.

City politicians used the police department early on as a source of patronage and to control law enforcement policies, especially on election day. After February 1866, a three-member board elected by and from the council had complete discretion in appointments and removals.

Denied any influence over the department for all but two of 20 years, a Democratic majority in the state legislature enacted a metropolitan police bill in 1883. Applicable only to Indianapolis, the law approved the appointment of police at a ratio of one officer per 1,000 citizens, with the proviso that the force includes an equal number of Democrats and Republicans.

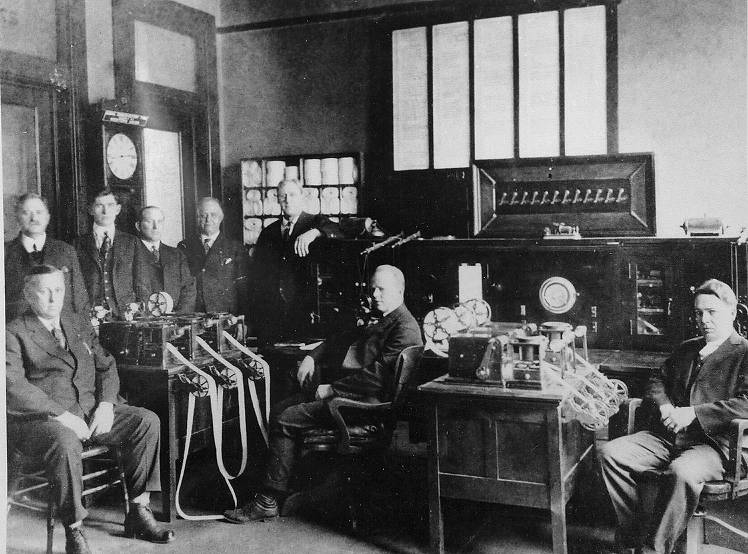

Mounted horse patrols and bicycle squads were employed before 1900 (and again in 1983 and 1990, respectively). To replace telephone booths first used in the late 1870s to keep street officers in touch with headquarters, the city spent $60,000 in 1897 on a Gamewell call box system, installed throughout the city. Beat police officers for the next half-century reported hourly and could summon help from headquarters. In the 1890s and for many years thereafter, IPD used the Bertillon system—a file collection of body measurements, photographs, and fingerprints— to identify criminals.

1891-1969

The City Charter of 1891 preserved the practice of dividing political spoils. It established a with three commissioners appointed by the mayor, only two of whom could be of the same party, and specified that the men of the police and fire departments be appointed on a bipartisan basis, a principle retained in the Cities and Towns Act of 1905.

In 1900, the city’s population reached 170,000, nine times what it had been at IPD’s founding. The size of the force kept pace, growing to 166, or one sworn officer per thousand residents. Paid $2.25 a day and required to purchase their own uniform and equipment, patrolmen worked 12 hours a day, seven days a week, with seven days of vacation after two years on the force.

The department was quick to adopt the latest policing methods. London’s Scotland Yard in 1901 was the first to rely on fingerprints, but Indianapolis organized a Criminal Identification Bureau in 1908 using fingerprints as the main tool after Albert G. Perrott (IPD, 1903-1949) witnessed a demonstration by Scotland Yard at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition. In 1904, the department was a pioneer with the first police emergency automobile. In 1906, trucks supplanted horse-drawn paddy wagons. The department included motorcycle police from 1909. Cars, motorcycles, and prisoner wagons quickly became the primary modes of transportation and patrol for the police force.

With both political parties guaranteed representation in the police department, the party in power influenced appointments, controlled promotions, and named the chief and high-ranking officers. A citizens’ report in 1917 recognized one consequence of this overtly political system of appointments: the failure to discipline officers who failed to follow departmental policy. In 1915, three officers and the chief were found guilty of election fraud. Prohibition proved a baleful influence, in the 1920s, and it was routine for gamblers and after-hours houses to pay protection.

By 1918, the police force added 14 women to its ranks, two of which were African American (Emma Christy Baker and Mary Roberts Mays). Within three years, IPD had the only female police captain in the United States, Captain Clara Burnside.

Innovations continued in the 1930s under reforming Chief : IPD’S first crime laboratory (1932), “drunk-o-meter” or breathalyzer (1937) (developed by Rolla N. Harger at the Indiana University School of Medicine), polygraph machine (1938), and the department’s first formal training school for recruits. The city trailed only Detroit and Cleveland in installing radio receivers in patrol cars (WMDZ began broadcasting Christmas Day, 1929). Two-way car radios appeared in 1939.

During World War II, the IPD suffered a labor shortage, which led to an increase in women hired for the force. Prior to this, the number of women officers had decreased to just 14 by 1939, most working in administrative roles. With fewer men on the force, women were able to take on more active roles like patrolling . After the war, the number of women slowly dwindled, and those who remained were once again relegated to office roles. The major post-war technological innovations included walkie-talkies and a juvenile division, introduced in 1948.

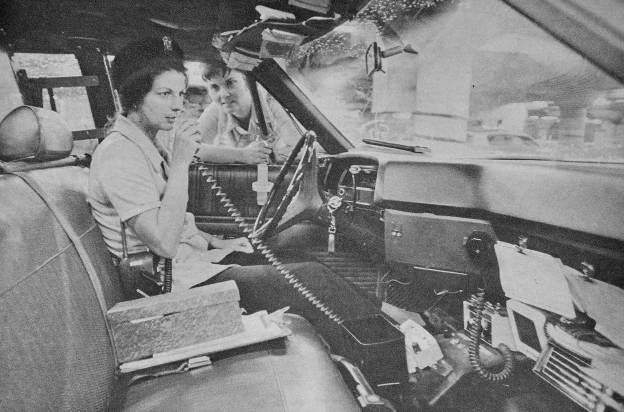

In the 1950s, IPD began to substitute lower-paid civilians for sworn personnel in clerical and administrative posts, a process pursued every decade since. The department introduced radar in 1951. As of 1957, officer patrol cars had 3-way radios that permitted communication with other cars as well as headquarters. A canine unit was established in 1960. The 911 emergency communications system was introduced in 1967, and in 1968, IPD got its first helicopters.

Scandal hit the department twice during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1956, a traffic-fixing scandal hit the department, and in 1964, 22 police were indicted for regularly taking bribes from the kingpin of the city’s numbers racket. Even after the end of Prohibition, it also was routine for gamblers and after-hours houses to pay protection through the 1960s.

It was not until 1968, policewomen were assigned use of patrol vehicles, with the first being Officers Elizabeth Robinson and Betty Blankenship. They were the first women assigned to patrol together in the United States.

1970-2006

Although the Indianapolis Police Department experienced many changes during the 1970s, it was not included in the Unigov consolidation. IPD continued to operate separately from the Marion County Sherriff’s Office.

In 1974, three reporters won a for articles alleging police brutality, pervasive political influence in appointments and promotions, shakedowns, defalcation of funds, ghost employment, and unsavory connections with brothels, known burglars, and fences. What was unusual about the 1974 expose was that over 50 officers violated the “code of silence” and supplied information to the reporters.

Historically, allegations of malfeasance in the department result in few or no convictions, although some officers retire or are reassigned or demoted. Such was the case in 1974. At the end of his term in 1975, Mayor confessed that reform of IPD had eluded his best efforts. From 1982 through 1991, a disciplinary board of captains found guilty over 98 percent of the 1,453 officers brought up on departmental charges ranging from tardiness to crimes.

The number of women and minorities in the police force, as well as their roles, shifted between the 1970s and 1990s. In 1972, 60 of 74 women worked exclusively in office jobs. It was not until 1976 that a woman, Officer Penny Davis, was assigned to the Investigations Division. Davis became the first women deputy chief in 1992, with Patricia Holman following two years later as the first African American woman with this rank. By 1992, women made up about 15 percent of IPD’s sworn-in officers. In 1978, minorities made up 18 percent of IPD’s officers. This number rose to just under 30 percent in 1992, due in part to the affirmative action program inaugurated by the administration.

The department added a Special Weapons Action Team (SWAT) in 1975, and computer-aided dispatch began in 1978. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, new technologies were introduced or improved. In 1989, fingerprint identification became automated. The 911 emergency communications system was enhanced in 1990, and a countywide radio system that linked all emergency agencies within Marion County (the Metropolitan Emergency Communications Agency) was put into place in 1992.

The blatant political interference so characteristic in IPD as recently as the 1970s was much reduced by the 1990s, as were the scandals and the perception of endemic, if often minor, corruption. High salaries (base salary for a third-year officer in 1994 was over $34,000), good benefits, and an excellent pension attracted a far larger pool of better-educated applicants than ever before. More sophisticated and more extensive training was developed: IPD trainees in 1993 spent 19 weeks (over 750 hours) in class gaining instruction in firearms, managing a crime scene, rescue and water safety, radio, interrogation and interview techniques, making an arrest, conducting a search, transporting prisoners, peacekeeping, cultural diversity, written communications, preparing for court, driving, and equipment maintenance. Completion of the course was followed by 15 weeks of field training working with experienced officers on the street.

Decentralization and Community Policing

Despite the introduction of increasingly sophisticated technologies, or perhaps because of them, the reported violent crime rate increased from 7.3 to 18.1 per 1,000 residents from 1970 to 1991, giving rise to the belief that radio patrol cars and over-centralization of IPD had isolated police from citizens. To enlist residents in the struggle against crime and to establish closer ties between the department and the community, IPD in 1976 initiated a neighborhood crime watch program and “community-based team policing” in 1977. Continuing efforts to decentralize service resulted, and in the late 1980s quadrant headquarters were moved out of the City-County Building:

- North District, 4209 North College Avenue, opened July 14, 1989.

- East District, 3120 East 30th Street, opened May 15, 1990.

- West District, 551 North King Avenue, opened April 16, 1991.

- South District, 1150 South Shelby Street, opened May 4, 1995.

- Downtown District, 209 East St. Joseph Street, opened April 1995 (since relocated to 25 West 9th Street).

In January 1992, the new mayor, Stephen Goldsmith, heralded a program to reorient IPD to “community policing,” which assigned more officers to neighborhood beats. Expected to develop expert knowledge and greater rapport with an area’s law-abiding citizens, beat patrol officers had greater discretion to solve problems. Detectives, no longer seen as specialists in certain crimes, were relocated to the districts, and in addition to quadrant headquarters, mini-stations were established in what was deemed problem housing complexes and shopping malls.

Intended to be in place in 1993, the shift of IPD to community policing was marked by delays and criticism, especially by police rank and file. Community policing is personnel-intensive, and in 1993, IPD found its human resources stretched to the limit. To find the needed personnel, the department continued its decades-long practice of moving sworn officers out of headquarters and substituting civilians. A new Public Safety Corps of non-sworn officers was developed in the mid-1990s. This group worked as evidence technicians, park security officers, and accident investigators, as well as transporting prisoners, further relieving sworn officers for neighborhood beats.

Race Relations

From the 1970s to the 2000s, IPD’s most serious problem was not a scandal but police-community relations, particularly with the African American community. Critics focused on controversial police shooting fatalities, harassment and excessive force, the citizen complaint process, and the absence of credible civilian review. Mirroring national trends, Indianapolis police action shootings and shooting fatalities reached their height in 1974-1976 (averaging 25 shootings and 8.3 deaths in those years), and then declined. Over the period 1970-1991, IPD averaged 10.4 shootings and 2.8 fatalities per year.

Despite the downward trend in shootings, controversial deaths of African American suspects at the hands of Indianapolis police continued. In November 1980, police fire killed a 15-year-old running from an officer; in September 1987, a 16-year-old suspected of auto theft, although handcuffed and in a police car, shot himself in what was ruled a suicide (see ); in July 1990, a young man of 25 was killed after a robbery and high-speed chase; and in June 1991, a suspected shoplifter, age 27, was fatally wounded. Except for the ruled suicide, all victims were unarmed and were shot by white male officers. Furthermore, many citizens did not accept the suicide verdict despite the unanimous finding of a half-dozen agencies, including the investigation by a retired African American IPD deputy chief. Black ministers and officeholders organized demonstrations around IPD headquarters, carried out economic boycotts, and called for the resignation of the mayor, the police chief, and other city officials.

For their part, police officers were embittered by the shooting death of an officer in August 1988. What began as a complaint about a dog escalated when police forcibly entered the house of Fred Sanders, a white schoolteacher. In the ensuing melee, the teacher fired a shotgun at the officers, striking one who died 10 days later. Police retaliated by beating Sanders at the scene. The teacher pled guilty to involuntary manslaughter; one officer pled guilty to excessive force and resigned from the department; another was acquitted of the same charges by a jury. Many citizens supported the teacher in the affair, and a jury found for him in a suit against the city, circumstances that the police found especially galling (see ).

When controversies arose regarding police, city administrations have turned to blue-ribbon committees to suggest reforms. Rising criticism of the use of deadly force and complaints of brutality led a human relations task force in October 1989, to recommend, and the city to adopt, a nine-member (six civilians, three IPD) Citizens Police Complaint Review Board. The board, lacking a budget, staff, and legal counsel, never operated effectively. When the in December 1990, explicitly removed its power to review police shootings, a mandate the board and the public assumed it had, it became moribund. By March 1992, there were four vacancies, and it sometimes lacked a quorum. Some observers, many sympathetic to police, believed civilian review to be in IPD’s interest. The , to improve trust between citizens and police, convened a 22-member task force on “police performance assessment” in August 1992.

The Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, 2007-

On January 1, 2007, the Indianapolis Police Department consolidated with the law enforcement division of the Marion County Sheriff’s Department to create the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department (IMPD). IMPD was established under General Ordinance 110, which assigned responsibility for the police department to the sheriff, who appointed a chief of police. The Marion County Sheriff’s Office lost its Road Patrol and Investigations Division while retaining control of the jail and City-County Building duties, warrants, and sex offender registry investigations.

About a year after the initial consolidation, the City-County Council amended the Revised Code to establish IMPD as the police division of the Department of Public Safety. With this change, IMPD operated under the day-to-day direction of a chief of police appointed by the Director of Public Safety.

IMPD’s rates of use-of-force and police shootings increased during the first half of the 2010s. Between 2014 and 2016, IMPD police officers were responsible for 16 fatal shootings. The department also reported 873 incidents of use-of-force in 2015 alone. In a positive move, IMPD launched their behavioral health unit during this period, which provided training to officers in dealing with mental illness and methods of de-escalation.

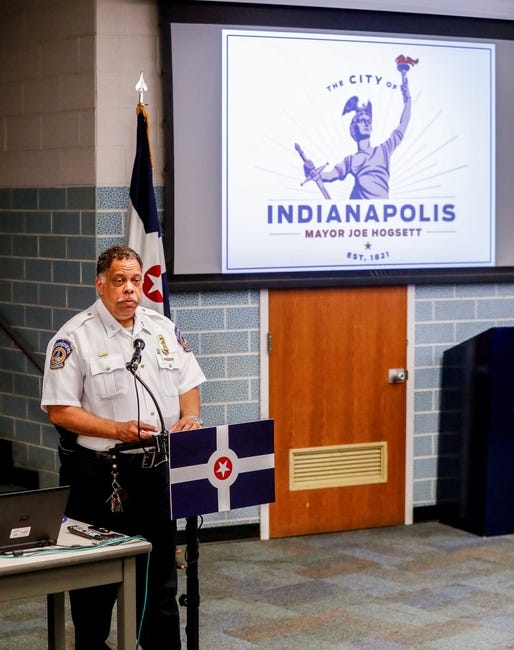

The IMPD went through yet another change in 2016. The City-County Council dismantled the Department of Public Safety following newly elected mayor Joe Hogsett’s proposal to reorganize IMPD. This dissolution established IMPD as a department of the City of Indianapolis. Under this structure, the chief of police was appointed by and reported directly to the Mayor of Indianapolis.

In the middle of 2017, another African American man was fatally shot by Indianapolis police officers. Aaron Bailey, who was unarmed at the time, was shot after a traffic stop-turned chase. The new chief of police, Bryan Roach, called for the two officers involved to be fired. The merit board, backed by the police union, decided otherwise, and the officers remained on staff. While this decision was controversial, it sparked a movement toward reform.

Between 2017 and 2019, Chief Roach began working with the community to determine what reforms were most needed. Officers began receiving training on implicit bias and de-escalating mental health crisis situations, and an office for diversity and inclusion was created as well as new units to better address behavioral health issues. This increased community outreach and commitment to change seemed to make a difference. By the end of this three-year period, the total number of fatal police shootings decreased to three.

Other changes were also promised during this period, including changing IMPD’s use-of-force policy, creating a new review board for uses of force, and reexamining the process for registering complaints against abusive officers. These recommendations were not adopted. Although fatal shootings were down, high rates of use-of-force continued. In 2019, an Indianapolis police officer came under scrutiny for punching a 17 -year-old African American student at Shortridge High School. This type of use of force was common and more often directed towards African Americans, with a rate of over 2.5 times that of white residents.

May of 2020 marked a significant moment for the already strained relationship between IMPD and the African American community. In the same month that the police murder of Minneapolis man George Floyd gathered national attention, two African American men (Dreasjon Reed and McHale Rose) were fatally shot by Indianapolis police. These shootings sparked months of protests and calls for police accountability and reform.

To ease tensions, IMPD pledged several reforms in July 2020. It adopted new use-of-force policies which prohibited the use of chokeholds, required de-escalation, and provided a clearer standard for deadly use of force. The new policies also provided updates to rules regarding the use of chemical spray and certain electronic devices such as tasers.

Developments since 2020

As of 2020, IMPD had 1,700 sworn officers and 250 civilian employees who operated in six districts throughout the county. Despite calls by some members of the public to defund the police, over $260 million was proposed for IMPD’s 2021 budget that would increase the department’s funding by $7 million. IMPD cited the increased amount as needed in order to maintain salaries, which make up over 80 percent of the budget. This budget also calls for $1 million towards body cameras, part of the reform promises made after the 2020 protests.

On January 3, 2021, two Indiana state senators filed a bill that would put IMPD in the hands of a state-appointed board. The bill’s authors’ Senator Jack Sandlin, a Republican representing Marion County, and Senator Scott Baldwin, a Republic representing Hamilton County, called for a five-member board “to provide a new level of governance and civilian oversight” and to reduce political influences.

The Indianapolis mayor and four members appointed by the governor would sit on the new governing body. The bill comes in the face of a record level of homicides and the 2020 protests. The two senators stated that they wrote the bill with the goal of rebuilding trust in the police department and providing “better services to the community, businesses, and visitors.” If enacted, the board would have taken over in 2023. The General Assembly, however, referred the bill that would have created the oversight board to a summer study by its Corrections and Criminal Law Committee.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.