Indianapolis has struggled with the issue of downtown development (or redevelopment) throughout much of the 20th century.

The automobile’s popularity in the 1920s and 1930s created a need for downtown parking, leading to the demolition of older buildings for parking lots. By 1944, according to the Indianapolis Real Estate Board, the most significant problems included vacant tracts, high tax assessments, and low or nonexistent revenue among rental properties within the . Indianapolis was not alone in the deterioration of its downtown area as residents were attracted to the residential and commercial developments in surrounding townships.

It was not until the 1970s that the city actively pursued downtown redevelopment in a budding revitalization movement. In 1972 the opened its doors. Two years later , a major recreational and sports facility, opened on the eastside of downtown near . Together, these venues attracted concertgoers, exposition attendees, and sports enthusiasts. Businesses also made a new commitment to downtown when companies including (1970, Regions Bank in 2020) and (1975, AT&T, inc. in 2020) constructed impressive new office complexes in the central business district.

New hotels and commercial structures followed, among them with its Hyatt Regency Hotel (1976). When became mayor in 1976 the city entered a new phase of downtown redevelopment, focusing on a strategy that would establish a market niche for Indianapolis and further redevelop the downtown core as the cultural and economic center of the city and region. An important element of the development plan involved marketing the city as a venue for sports events and as the headquarters for amateur sports organizations.

This movement originated in 1970 when members of the Sports Capital Committee persuaded the to locate its headquarters in Indianapolis, which occurred during the Hudnut years. Equally important was the creation of the (IPI) and the Indianapolis Growth Project (IGP) in 1981. Jointly sponsored by the city, the , the , and the Convention Center, IPI assisted and encouraged companies considering a move to or an expansion downtown.

Within a few years Indianapolis Project, Inc., became an image-building organization focused on positive local and national media attention on the city. The Indianapolis Economic Development Corporation took over the development responsibilities of the IGP in 1983. Indianapolis’ plan fit important theories of development. There was a clear geographic focus: the downtown area. This emphasis capitalized on existing assets and several public investments, including a government center employing thousands of state and local government employees, a large private-sector employer (), and a developing state university campus (, or IUPUI) with a hospital and health services center ().

During the Hudnut years, public and private initiatives led to more than 30 major development projects for the downtown. Concurrently the investment in IUPUI totaled more than $231 million. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the State of Indiana provided additional stimulus by developing its new State along West Washington Street between Senate and West streets at $264 million. In addition, one specific industry—sports—created a market niche for Indianapolis, one with substantial symbolic value to society and the potential to attract future support.

Five downtown projects were directly related to the sports identity Indianapolis had begun to establish with the construction of Market Square Arena. In 1984 the city opened the 61,000-seat , (later renamed the RCA Dome), which became the home of the and which served four times as a venue for the NCAA Men’s Basketball Final Four. Other facilities included the Tennis Center, a stadium for the annual hardcourt championships; the Indiana University Natatorium; the Indiana University Track and Field Stadium; and the .

In addition, the private and nonprofit sectors financially aided several to relocate to the city. By 1989 seven national and two international organizations had moved their governing offices to Indianapolis. While many were located in the suburbs, their presence signaled local interest in the use of amateur sports as a means of attracting athletes and sports enthusiasts to downtown facilities.

The city also encouraged other development activities. The 1980s witnessed scores of downtown building projects. Among them were the first single-family residential structures constructed in the Mile Square in over 100 years; completion of several major buildings including (1988, 32 stories), (1982, 38 stories), ( in 2020), and (1990, 51 stories) ( in 2020); rehabilitation of the adjacent to West Street (1991); and construction of the new (1985).

Other projects were less successful, at least initially. The , for example, unveiled plans in 1982 but aside from site preparation, no work began on the project until 1989. Several things stymied the mall development, ranging from the inability to sign major retailers to the project due to a national recession to the opposition from historic preservationists who decried the demolition of many historic buildings from the city’s 19th century.

The next decade saw $2.76 billion (equal to $4.15 billion in 2020) invested in downtown capital projects. There was an extensive commitment of private funds to the strategy. Indeed, more than one-half of the funds invested, 55.7 percent, came from the private sector. The nonprofit sector was also an active participant, responsible for almost 1 of every 10 dollars invested, or 8.5 percent. This reflected the success of the public-private partnerships that city leaders had emphasized beginning in the 1970s and 1980s.

Taken together, the private and nonprofit sectors were responsible for approximately two-thirds of the investment in amateur sports and downtown redevelopment strategies. The City of Indianapolis’ commitment amounted to less than one-fifth of the total investment, 15.8 percent. The city successfully leveraged funds for economic development: a $2.76 billion investment for an economic development program required $436 million from the city.

For every dollar it invested, the city was able to secure $5.33 from other sources. The State of Indiana and Indiana University invested more—$495 million—than did the city itself. As a result of this successful strategy, downtown employment increased measurably between 1970 and 1980 and remained steady in the 1990s.

The city also gained new and favorable exposure to national and international audiences, which stimulated continued development. In 1987, the city’s investment in a sports strategy paid off when Indianapolis hosted the . Indianapolis secured the games when previously selected hosts Chile and then Ecuador backed out due to economic conditions. Since the city had begun to invest early in its sports infrastructure, it was able to step up and host the event that drew nearly 4500 athletes from 38 western hemisphere countries competing in 30 sports at different venues around the city. With this three-week event, Indianapolis established itself as a location capable of hosting major public gatherings and sporting events, which led to continued considerations as a host city for and even the NFL’s .

By the 1990s Indianapolis had redefined its skyline, gained a sports reputation, and polished its image as a commercial and business location. Secure in the success of earlier administrations’ efforts, Mayor in 1992 began to shift the focus of development toward the neighborhoods while maintaining a healthy interest in completing long-planned downtown projects such as the controversial Circle Centre Mall, which opened in 1996. While the project attracted local, national, and international retailers to the downtown site, by 2020 the mall faced challenges posed by increased online retailing, forcing mall owners and city officials to consider the future of new redevelopment options.

With an increasingly vibrant downtown and new national and international recognition for its ability to host athletic events, Indianapolis leaders chose to continue their sports initiative by providing newer, technologically advanced venues to serve their sports fans and visitors. In 1999 the city constructed a new basketball arena, (formerly Conseco), at S. Pennsylvania and Georgia streets to house the NBA team. The city, in conjunction with the local minor league baseball team , constructed at the corner of West and Maryland streets to replace the Indian’s original home at (1931-1996). Finally, the city, in conjunction with the Indiana Stadium and Convention Building Authority, provided a new home for the Indianapolis Colts by constructing along South Street. The stadium, which opened in 2008, seats approximately 67,000 spectators and includes a retractable roof. These state-of-the-art sports venues attract hundreds of thousands of people to downtown every year and pump millions of dollars into the local economy.

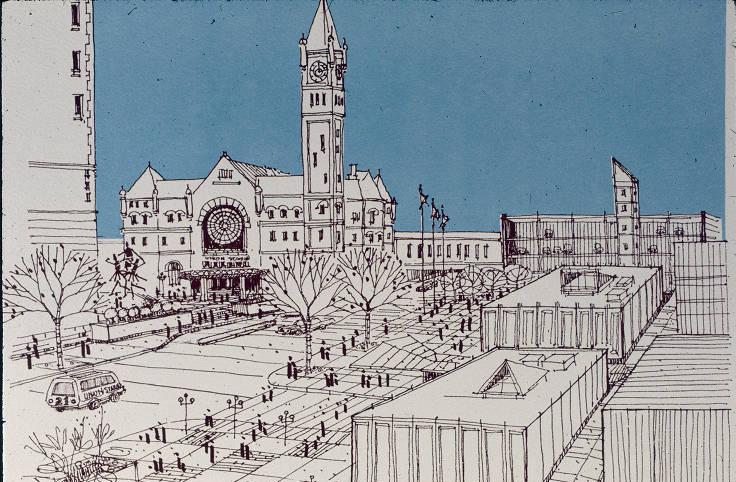

Two other projects also sought to reinvigorate the downtown. During the early 1980s, local developers launched a restoration of , constructed in 1887-1888, and created a festival marketplace with retail space, restaurants and nightclubs, offices, and a high-end hotel located in the former train sheds. While the project initially attracted great attention and support, it gradually lost retailers and businesses due to low revenues and growing competition from nearby Circle Centre Mall. Most of the space has since been converted to office and meeting space while a large banquet/special events space remains in the Great Hall of the station and the hotel continues in the restored train sheds. Another innovative downtown development is the . The domed structure spans the intersection of West Washington and Illinois streets and serves as a pedestrian corridor between neighboring buildings and Circle Centre Mall. Owned and operated by the , it also serves as a venue for performances and art exhibitions.

The 2010s have seen a surge in downtown development, thus demonstrating its vitality and the desirability of working and living in the area. Thus, the work begun in the 1970s continues to yield positive results.

Most visible on the downtown landscape has been the conversion of vacant buildings into hotels, apartments, and condominiums as well as new construction of high-density housing on the former site, along the Canal, on the former Market Square Arena site, and elsewhere around the Mile Square. One of the newest developments scheduled to open in 2021 is the , housed in the former building along Massachusetts and College avenues. This multi-use facility includes condos and apartments, a hotel, offices, and restaurants.

The Conrad Hotel and Condominiums, part of Hilton Hotels & Resorts, opened its 23-story building at the northeast corner of West Washington and Illinois streets in 2006, thus making Indianapolis one of six American cities with one of these luxury hotels.

, an Indiana-based manufacturer of gas and diesel engines and other generating systems, constructed a multi-story, energy-efficient distribution headquarters on part of the former Market Square Arena site.

In May 2013 the opened to the public. Founded by the in partnership with the City of Indianapolis and with significant funds from and , the trail is an 8-mile bike and pedestrian path that covers a good portion of the original Mile Square. It has contributed to a resurgence of neighborhood redevelopment in and the .

Reflecting efforts at centralizing public transportation services a century earlier with the opening of the , the city constructed the Transit Center across from the City-County Building in 2016. This facility serves as the center of , the city’s public transportation company.

Other projects over the past couple of decades that have contributed to the overall development of the downtown include: , which includes the and the ; The Indianapolis Canal Walk which references the city’s connection to White River and Central Canal; and the national headquarters of the (NCAA), which relocated here in 1999.

The city’s dedication to ongoing redevelopment continues to be evident in recent actions taken by public and private sector leaders. . a private non-profit organization, was founded to promote downtown Indianapolis. Like the of the late-19th century and the Indianapolis Project of the 1970s, Downtown Indy assists with civic events and conventions, promotes economic development, supports downtown living, and collaborates with civic and business leaders to ensure the vitality of downtown.

In August 2020 the City-County Council approved funds to expand the Indiana Convention Center, which sits at the southern edge of the Mile Square and which plays a significant role in the economic life of Indianapolis by hosting conferences, sporting events, business shows, and large public events like the gaming gathering . The council also approved plans for two new high-rise hotels on (bound by Capitol, Illinois, Georgia, South streets).

The COVID-19 pandemic cast a shadow over these developments. Despite this, local leaders remained committed to maintaining the aggressive redevelopment of the downtown area but with the acknowledgment that a “new normal” would affect the vision of Indianapolis’ future.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.