Photo info ...

(Nov. 25, 1897–May 25, 1974). Edna Martin was born as Edna Mae Barnes on a farm near Mount Vernon. The previous year, her parents, William Barnes and Lemah Jones Barnes, had left their home of Paducah, Kentucky with their one-year-old son to start their journey to Indianapolis. Their first stop was near Mount Vernon in 1897, where Edna was born. The family stopped again in Baptisttown, an African American community in Evansville, where a daughter named Lucile was born in 1900. The Barnes family finally arrived in Indianapolis in 1901 (settling initially at 824 Scioto Street), where they would have four more children.

Because the family moved often, Martin attended several , including numbers 17, 23, and 24. In the early 1910s, Martin attended . Though no record of her graduation exists, family history indicates Barnes did graduate from Shortridge.

Throughout Barnes’s youth, she spent long hours outside the home to supplement the family income—working as a housemaid, a factory worker, a waitress, and a clerk. She also spent time working within her church. played an influential role in Barnes’s teenage life. Reverend George W. Ward, pastor of Mt. Zion, baptized her when she was 17. One of her first missionary deeds included bringing her mother and six siblings to the church for baptism. Barnes became the local president of the Lott Carey Missionary Society at age 19. This group worked with the American Colonization Society (see ), for which Barnes helped raise funds for the construction of a hospital in Liberia.

Barnes met her future husband, Earl Martin, at a . The two married at Mt. Zion on September 12, 1921. Martin and her husband had two children, daughter Doris Lillian (born 1922) and son Earl Jr. (born 1924). The children attended Indianapolis Public School No. 42. In 1936, Doris Lillian attended the segregated Booker T. Washington Junior High School. At the end of January 1937, at the age of 14, she died from a sudden attack of enteritis (inflammation of the small intestines). After Doris’s death and the death of her mother on April 4, 1940, Edna Martin fell into despair, though she never questioned her faith. According to oral histories from friends of Martin, she experienced a spiritual rejuvenation on her twentieth wedding anniversary. She told a friend that “God spoke to me,” and in 1941, Martin answered.

In 1941, the city of Indianapolis conducted a survey that found 75 percent of crime in Indianapolis occurred in the near northeast side neighborhood of (part of the larger Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood beginning in 1992). At the same time, the conducted its own research which revealed a high rate of juvenile delinquency in the same area. Based on this information and convinced that God “had called her out” to rescue the children living in Martindale, the 43-year-old Martin decided to help the area’s at-risk youth.

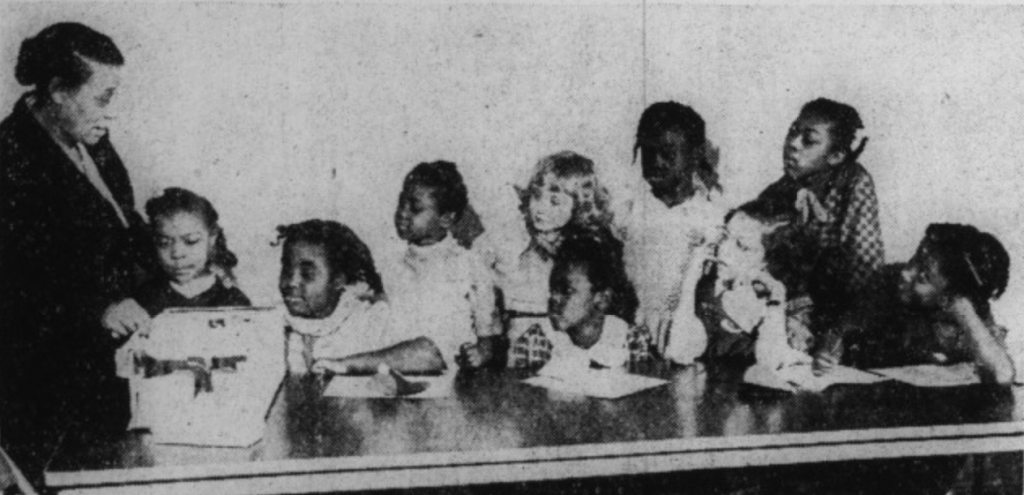

Martin rented a one-room apartment for $14 a month. There she opened a Christian daycare program for two young girls. Within a year Martin’s daycare outgrew the apartment. Unable to afford a larger space, Martin relocated the daycare to a large outdoor tent.

In 1945, Martin received the financial assistance she needed. A committee from the All Baptist Fellowship—a cross-racial group representing Woodruff Place Baptist Church from the white community, Good Samaritan Baptist Church of the Black community, and Garden Baptist Church of the white community—interviewed Martin and decided to sponsor her effort. With their financial help, she formed the East Side Christian Center in a three-room house at 1519 Martindale Avenue (now Dr. Andrew J. Brown Avenue). Located across the street from , the Center under Martin’s leadership soon added an after-school program and a children’s choir to its offerings. By 1949, the Center had outgrown that location and moved to 1537 North Arsenal Avenue.

With the support of the Baptist churches, the Center grew into an organization that steadily transformed the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood. By the 1950s, studies showed that delinquency had dropped dramatically, a development for which the sponsoring church bodies and neighborhood leaders gave Martin credit.

Though much of the Center’s success lay with Martin, her idiosyncratic and determinedly independent leadership style hampered relations with partners and funders. Martin tried to balance the needs of the Center’s clients with the demands of the Indianapolis Baptist Association, which had taken over the Center in the early 1950s, but friction surfaced over the management and overall vision for the Center. In 1957, the American Baptist Home Mission Society conducted a review of the Center’s operations. While praising its effectiveness, the review revealed a lack of formally trained staff, including Martin herself. Martin agreed to attend leadership conferences to gain administrative skills and also arranged for the staff to acquire training.

In later years, Martin remained committed to the Center and successfully rallied support from white and Black communities, individuals and foundations, urban centers, and country towns. In recognition of her accomplishments, accolades and honors poured in during the last decade of her life. She received awards from Sertoma International, the American Baptist Home Mission Society, and the Indianapolis Church Foundation. The National Council of Negro Women included her in the Black Women’s History project. Wilma Taylor’s biography of Martin titled Sisters of the Solid Rock is part of the archival holdings at the National Archives Research Center in Washington, DC.

awarded her an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree in June 1965. The Independent Colleges of Indiana inducted Martin into the Indiana Academy alongside the likes of , , and in 1972. In that class of 18 recipients, she was the only woman, the only Black honoree, and the only one lacking a college education.

Martin continued to work with great fervor until she died in 1974 from breast cancer. After her death, the Board of Directors of the East Side Christian Center renamed the organization after Martin to honor her 33 years of leadership.

FURTHER READING

- Taylor, Wilma Rugh. Sister of the solid rock: Edna Mae Barnes Martin and the East Side Christian Center. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2002. https://cdm16797.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/IHSPub/id/3499.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Crabtree, D. (2025). Edna Martin. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 15, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/edna-martin/.

MLA:

Crabtree, Dale. “Edna Martin.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025, https://indyencyclopedia.org/edna-martin/. Accessed 15 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Crabtree, Dale. “Edna Martin.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025. Accessed Feb 15, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/edna-martin/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.