Black residents have fought for civil rights and participation in politics from the beginning of the city’s history. Indiana’s 1816 Constitution barred African Americans from voting and holding public office. Indianapolis had a growing African American population from the time of its incorporation in 1821, and white segregationists, who wanted to keep them and other minorities from voting or holding public office, strongly discouraged Black participation in politics. Yet as early as the 1840s African American leaders in Indianapolis such as barber and Baptist layman John G. Britton made frequent appeals to white Hoosiers for the rights and privileges to which Black citizens were entitled. During the 1840s and 1850s, Blacks from around the state occasionally met in Indianapolis prior to meetings of the Indiana General Assembly to petition for equal treatment under the laws. These early political efforts failed to garner public sympathy and did little to improve their status. In fact, the state’s new 1851 Constitution prohibited the future immigration of African Americans into Indiana.

Civil War and Reconstruction, 1860s-1870s

From 1860 to 1870, the number of Black residents in Indianapolis increased by almost 500 percent, particularly after 1865. In the years following the Civil War, Indianapolis African Americans pursued equal legal rights with whites. Black representatives from 30 Indiana counties met in Indianapolis in October 1865, to seek the repeal of discriminatory laws. With the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, local African Americans felt that they finally had achieved the political rights for which they had struggled so long. They soon discovered that the right to vote and hold public office did not result in the immediate improvement in their condition. During the election riot of 1876, a white mob and rogue police used intimidation and violence to suppress the Black vote. As a result, the political influence of Blacks did not reflect their relatively large presence.

Contributions in the Face of Discrimination, 1880s-1910s

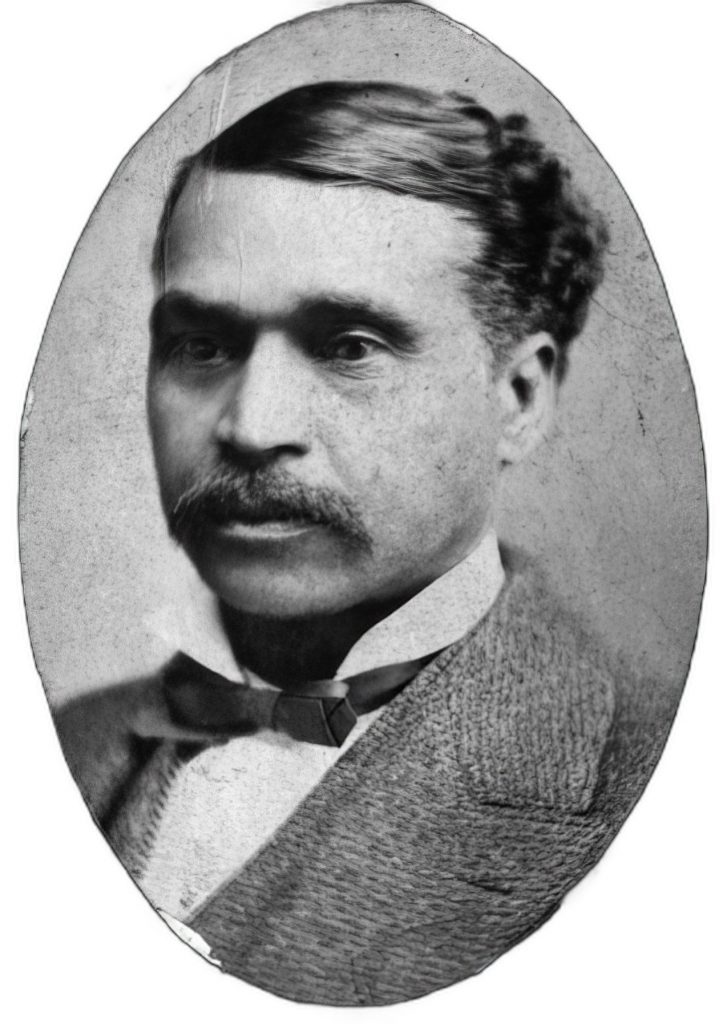

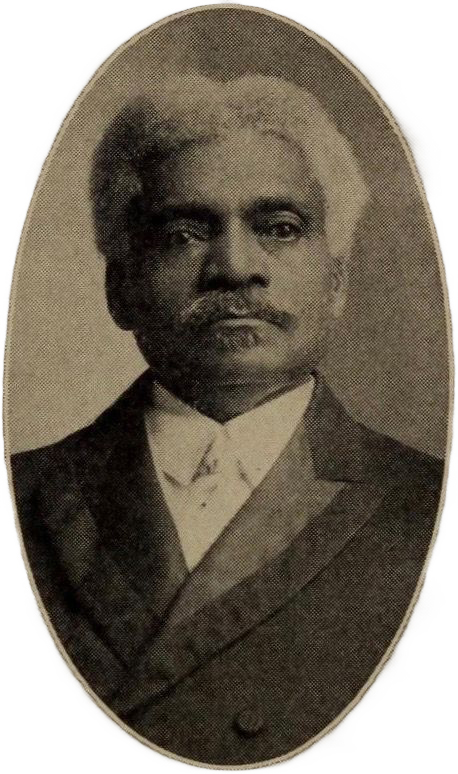

That began to change in 1880 when , an Indianapolis Republican, became the first African American elected to the Indiana General Assembly. His term as a state legislator marked the first significant political victory for African Americans in Indiana. Two years later, African American physician defeated Hinton in his bid for renomination, but Elbert and other Republican candidates were defeated in the general election. In 1896 Tennessee-born Gabriel L. Jones, an Indianapolis school teacher and advocate for equal educational opportunities for Blacks was elected to the House after serving as Marion County deputy recorder (1895-1897).

Painting Democrats as racists, Republican candidates regularly courted Black voters, capturing them as a bloc until the 1920s. Dissatisfaction with the Republicans’ deteriorating civil rights stance in the post-Civil War years did not produce an exodus of Black voters from the party. However, an African American Democratic club was active in the city from the late 1870s and particularly in the municipal elections of the late 1880s. Alexander E. Manning, lawyer and editor-publisher of the , and , Indianapolis’ first African American lawyer, were for many years the backbone of the African American Democratic movement in the city and the state. Manning was the official courier for the Democratic national committee for 30 years and served as president of the convention of the National League of Negro Democrats (1896). Although African Americans resisted ongoing Democratic attempts to woo them nationally and statewide throughout the late 19th century, large numbers of Indianapolis Blacks cast their votes for , a white Democrat, thereby helping him to win three successive terms as mayor.

Traditionally, African American ministers have played a conspicuous role in city politics. The Reverend of the was an ardent Republican supporter. Another Baptist minister, R. McCary, was one of two Black delegates from Indiana to the Republican national convention of 1872. Other examples of local ministers involved in African American politics over the years were J. P. Thompson, , Benjamin F. Farrell, Henry L. Herod, Charles H. Johnson, , and Landrum E. Shields.

In the late 19th century publishers and editors of local African American newspapers, including the , ,

Almost 10 percent of the city’s population was African American by 1900, which was higher than the percentage of Black residents in larger northern cities such as New York and Chicago. Despite this increase in the city’s Black population, between 1898 and 1932 no African Americans from Indianapolis were elected to the state legislature. During the same period, no legislation was sponsored at the municipal or state level by either party which might be regarded as having a special appeal for African Americans. Instead, Indianapolis switched from a ward to an at-large system for the election of council members in 1909 in an apparent attempt to dilute the Black vote.

Nevertheless, Black voters used their increasing numbers to have a stronger voice in city elections. Henry Sweetland represented the third ward on the City Council from 1890 to 1892. African American businessman was elected to the Indianapolis City Council in 1892. He was followed almost three decades later by , a physician who served from 1917 to 1921.

From Ku Klux Klan Opposition to Civil Rights, 1920s-1960s

The rise of the as a dominant force in Indiana politics in the 1920s aroused African American voters in Indianapolis. When the Ku Klux Klan dominated the Indiana in the 1920s, many Black voters left “The Party of Lincoln” and began voting for Democratic candidates. In May 1924, John Bankett of Indianapolis became the first Black Democrat nominated for the Indiana General Assembly. George Knox and his previously pro-Republican Freeman newspaper encouraged local African American voters to support the Democrats. This historic shift occurred in Indiana a decade before Blacks changed parties nationally during the Great Depression. Yet it was not until the mid-1930s, in response to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, that African Americans began defecting in large numbers to the . During these years Black candidates from both major parties were elected to public office, thereby increasing the political power of the African American population.

In 1932, , an Indianapolis attorney, became one of the first African American Democrats elected to the Indiana House of Representatives. Another prominent attorney, Republican , was elected as the first Black state senator in 1940. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Richardson and Brokenburr provided strong bipartisan support for laws protecting Black civil rights. They worked within their respective parties to guide the passage of legislation that fought discrimination in public accommodations, promoted fair employment practices, and ended discrimination in public education.

African Americans made slow but gradual progress in winning elections or appointments to local government positions. Over the years, Blacks most commonly held the position of Marion County deputy prosecutor. Henry Brokenburr became the first African American deputy prosecutor in 1919 and remained in the position until 1931. served in that post (1939-1941) before becoming Indiana deputy attorney general (1941-1943) and judge of the Marion County Superior Court (1958-1978).

The Democrats’ emphasis on beginning in the late 1940s launched them as the principal party of African American voters in the ensuing decades. While Republicans gained strength elsewhere, Indianapolis wards heavily populated by African Americans continued to support Democratic candidates.

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, Black elected officials worked with organizations such as the local , and other advocacy groups to expand economic opportunities for African Americans. Influential African American civic leaders such as businessman , a Republican, and prominent doctor , a Democrat, urged their political parties to nominate more Black candidates.

Andrew J. Brown Jr. championed civil rights from the pulpit of the St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church and organized a voter registration drive to demonstrate voting Black strength during the 1963 election. As a result, attorney Rufus C. Kuykendall and Rev. took seats in the 1964 City Council. Robert Collins, a physician, became the first African American to hold countywide office when he was elected Marion County Coroner during the Democratic sweep of 1964. That same election, of Indianapolis became the first African American woman elected to the Indiana General Assembly.

Strong Democratic support for passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1961 and 1963, the Fair Employment Practices Act, and the Indiana Civil Rights Commission (ICRC) led most Black voters to support Democratic candidates.

Unigov and Its Consequences, 1970s-1990s

By 1968 City Hall seemed within reach of Indianapolis’ African Americans. However, in 1969, Republican majorities in the Indiana General Assembly approved a bill that created Unified Government () in Indianapolis. The 1960s ended with Republicans leading the state and its capital city.

Unigov merged duplicate functions of the city and county into one city-county government. Diverse urban areas of Indianapolis were combined with the mostly white and rural municipalities of suburban Marion County. Republicans and other supporters of Unigov promoted it as a way to make local government more efficient. They also noted that the old “at-large” council voting system that historically diluted the African American vote would be replaced by a district system that better represented Black areas.

Opponents of Unigov dismissed it as a Republican power grab that would reduce the political power of Democrats and Black residents by incorporating mostly Republican suburban areas. Also, since the majority of African Americans were Democrats, their participation would be limited in a city-county government led by Republicans.

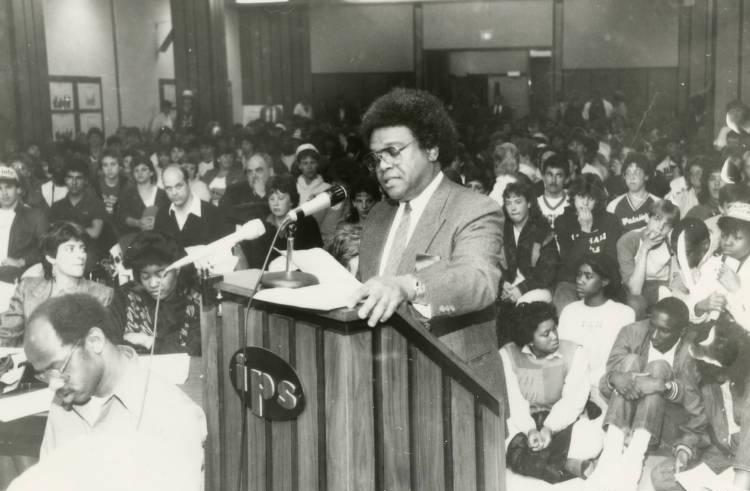

Unigov automatically returned the voting power of African Americans to what it had been in the 1940s. The African American share of the city’s population dropped from over 30 percent to less than 18 percent. Republicans dominated city government for the next 30 years.

However, Mayor , a Republican who served from 1976 to 1992, was popular among most African American voters. He worked closely with Black organizations and spoke frequently with Black news media. In 1978, Hudnut appointed Joe Slash as the city’s first African American deputy mayor, and Paula Parker-Sawyers became the first African American woman to serve as deputy mayor, also under Hudnut. Each mayor since has had a Black deputy mayor in their administration: Robert L. Wood (, 1992-2000); Eugene Anderson, Steve Campbell, Carolyn Coleman, Bill Shrewsberry (, 2000-2008); Olgen Williams (, 2008-2016); David Hampton, Angela Smith Jones (, 2016-).

Other local Blacks held positions in Indianapolis-Marion County government, including (director, Indianapolis Department of Parks and Recreation, 1975-1979), Benjamin Osborne and (Center Township trustee), Joseph D. Kimbrew (first Black fire chief, appointed 1987), and James D. Toler (first chief of the Indianapolis Police Department, appointed 1992).

In 1995, Democrat became the first African American and the first woman nominated by a major party to run for Indianapolis mayor. She lost to Republican incumbent Stephen Goldsmith. However, her campaign motivated other African Americans to run for higher offices.

In 1996, Julia Carson was elected as the first African American and first woman to represent the 10th (later 7th ) Congressional District, which covers most of Indianapolis. Carson’s victory was a pivotal moment in local politics. Her supporters built a strong coalition of Black community activists, white progressive leaders, and organized labor to help Carson defeat better-funded opponents in the Democratic primary and the general election. This same Get Out The Vote (GOTV) coalition was instrumental in getting other Democrats elected to office. With her accessibility to constituents, a down-to-earth personality, and the ability to work across party lines, Carson remained in office for a decade. Upon her death in 2007, she was succeeded by her grandson Andre’ Carson, who has won each election with more than 60 percent of the vote.

Increased Opportunities with a Democratic Party Majority, 1999-

By the end of the 20th century, the 32-year Republican lock on city government under Unigov began to crumble. Registered Democrats increased their numbers rapidly as numerous Republican voters moved to surrounding counties. Since most African Americans were registered Democrats, their participation in politics increased as the fortunes of the party improved. Black candidates enjoyed more opportunities for elected office after decades of being limited to the inner-city areas of Center Township.

As a result, when Democrat Bart Peterson was elected mayor in 1999, and reelected in 2003, several African Americans also took office as new members of the City-County Council. In 2004, became the first Black president of the City-County Council. Since then, a succession of Black leaders—Steve Talley, Monroe Gray, Maggie Lewis, Stephen Clay, and Vop Osili—have held that powerful position for most of the last 20 years.

Over the next decade other African Americans won county-wide offices, including Michael Rodman as treasurer in 2004, Billie Breaux as auditor (the first African American woman to hold countywide office) in 2008, and Myla Eldridge as county clerk in 2014. , a retired U.S. marshal, became the first African American elected Marion County sheriff in 2002. Since 2005, a succession of African Americans, Dr. Kenneth Ackles, Dr. Frank P. Lloyd Jr., and Dr. LeeAndrea Sloan have served as Marion County Coroner.

Local Black politicians also began to have a greater role in state government. In 2003, State Representative , an Indianapolis Democrat, became the first Black chairman of the powerful “budget-writing” House Ways and Means Committee. Marvin Scott, an Indianapolis professor, became the first Black candidate for the U.S. Senate in Indiana when Republicans nominated him to run against incumbent Democrat Evan Bayh in 2004. Barack Obama’s historic presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012 also led to a massive boost of Black voter registration and turnout.

Between 2000 and 2020, several African Americans from both political parties were elected to serve as judges in Marion County courts. One of the most notable examples was Sheryl Lynch, who became the first African American and woman to serve as a county circuit court judge.

On the township level, Black trustees, assessors, and judges were elected as Democrats won control of suburban Lawrence, Pike, Warren, Washington, and Wayne townships.

By 2015, Democrats held all of the major offices in Marion County, with Republicans holding power only in southern townships. As Democrats consolidated their hold on city government, Black Republicans faded from view. No African American Republican has been elected to the City-County Council since 2007. Jose Evans, the last Black GOP member, left office in 2015.

By 2020, African Americans represented more than 27 percent of the Indianapolis population, which was much higher than the national percentage. During the municipal election, progressive Black activists fought for a stronger voice in the traditional Marion County Democratic organization. At the same time, African American leaders called on Mayor Joe Hogsett and other city officials to handle issues of concern to Black residents.

The (AACI), an umbrella group of Black organizations, pressed the 2019 candidates for mayor to adopt what they described as a Black Agenda. That agenda, they asserted, should have included specific solutions to problems such as rising crime, challenges facing Black men, and high unemployment.

Hogsett did not adopt the Black agenda, saying that his administration was already addressing the concerns of African American residents. Hogsett’s Republican opponent, State Senator James Merritt, incorporated the Black agenda into his campaign but failed to excite voters overall. Hogsett was reelected in a landslide with significant Black support. Democrats won a 24-5 supermajority on the City-County Council and retained African American Vop Osili as council president.

FURTHER READING

- January, Alan F., and Justin E. Walsh. A Century of Achievement: Black Hoosiers in the Indiana General Assembly, 1881-1986. Indianapolis: Select Committee on the Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly in cooperation with the Indiana Historical Bureau, 1986. https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/14198252.

- Pierce, Richard B., ed. Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970. Indiana University Press, 2010. https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/70704959.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Little, M. H., Jr. & Perry, B. (2021). African Americans in Politics. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 15, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-politics/.

MLA:

Little, Monroe H., Jr. and Brandon Perry. “African Americans in Politics.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-politics/. Accessed 15 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Little, Monroe H., Jr. and Brandon Perry. “African Americans in Politics.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Feb 15, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-politics/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.