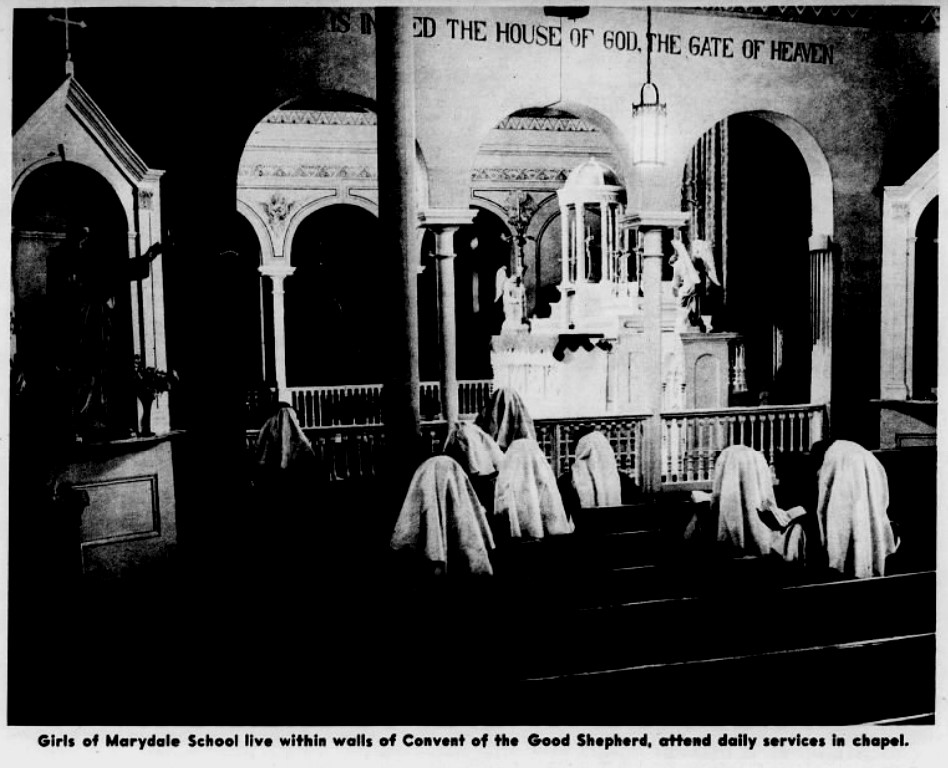

The Sisters of the Good Shepherd, a order founded in 1835 in Angers, France, opened the House of the Good Shepherd, in Indianapolis for “erring women and girls” on March 19, 1873. It stood on property on the south side that was donated by banker and designated by the city as the site of a “House of Refuge and Reform for abandoned Females.” In alignment with what Indianapolis city leaders intended, the nuns described their facility as “a place of retreat . . . for young women and girls, who having entered a wrong way of living, or who were in some other moral danger, desired to do better and begin a new life.” Although classified as a charity and refuge, evidence reveals that the religious order operated the House of the Good Shepherd like a correctional facility.

The Indianapolis location was the fifteenth House of the Good Shepherd established in the United States. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd founded the first in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1843. By 1900, the religious order had created at least 37 others across the U.S., in such cities as Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Baltimore.

Although women sent to the House of the Good Shepherd could be prostitutes, unmarried and pregnant, or condemned as adulterers, those merely considered at risk of engaging in promiscuous or immoral behaviors, including orphans and those born out of wedlock, were often confined in the institution. Families and priests placed women in the House of the Good Shepherd. Some who found themselves in desperate straits came of their own volition, but the city government also sanctioned its operation.

Soon after it opened, Marion County authorities declared that the House of the Good Shepherd was “a suitable place for Judges to send women guilty of minor offenses.” The city allowed for the transfer of Fletcher’s property to the religious order with the understanding that it would “receive Prisoners for half the price that the city was accustomed to pay for them.” This fee amounted to $2.00 per week for each female prisoner. The House of the Good Shepherd was funded through this arrangement with the city until 1887, though the courts thereafter continued to send some women offenders to the facility. Records show that, between 1877 and 1887, the Indianapolis City Court sent 398 women to the House of the Good Shepherd. Younger women and girls also served their terms of detention there. In 1904, the Marion County Juvenile Court, for example, noted it sentenced seven girls to the institution.

Other funding for the institution’s operation came through donations from the Catholic church, Houses of the Good Shepherd throughout the U.S., and charity collections from the local community. The Indianapolis House of the Good Shepherd also operated a Magdalene laundry, where the facility took in washing from local businesses and households. This laundry, where inmates worked unpaid, became the institution’s primary source of income.

Although Magdalene laundries were most prevalent in Ireland, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd established them in their convents throughout the U.S. These laundries traced their roots to asylums established in the 1600s in Europe for fallen women, considered guilty of moral crimes. Named for Mary Magdalene, a follower of Jesus in the Bible who has been described as a repentant prostitute, the institutions provided spaces where women symbolically could “wash away” their sins while scrubbing society’s dirty laundry.

The order in Indianapolis initially operated its Magdalene laundry in an outdoor shed, but, by 1882, the nuns had constructed a facility that included a washhouse, ironing room, and packing room. They later added a second level to the laundry with the introduction of steam technology.

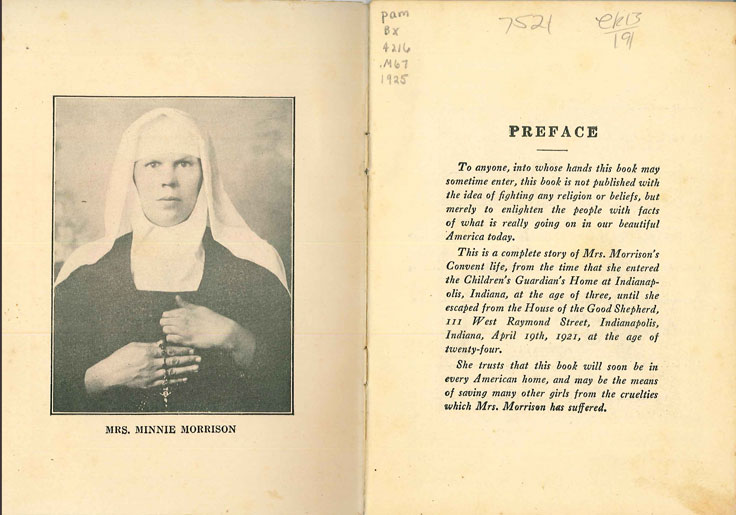

Women sent to the House of the Good Shepherd were held in basement rooms that were separated into cells. The windows were barred. Work in the laundry was unpaid, harsh, and frequently unsafe. For example, Minnie Morrison entered the laundry in 1901 at age 10 and “had to stand on a wooden box to iron her quota of 500 handkerchiefs a day.” The sisters gave her this assignment even though she was “not tall enough to see over the ironing board.”

In addition to forcing these women and girls to engage in unpaid labor, the sisters stripped them of their identities by giving them new names, deprived them of any contact with the outside world, and often inflicted severe punishments. Testimonies from those confined in the institution indicated that the sisters regularly slapped, flogged, and punched them. In a memoir published in 1925, Morrison claimed that the nuns placed inmates in a dungeon-like basement where they were fed only bread and water for weeks, and she stated that she had seen nuns beat residents to the point of unconsciousness. The sisters burned four of Morrison’s fingers as a punishment. Left untreated, her fingers later had to be amputated.

Women were held against their will sometimes for years and even for life. Newspapers include several accounts of escape attempts. In 1910, Morrison won a monetary award in a lawsuit against the House of the Good Shepherd for “false imprisonment.”

The Sisters of Good Shepherd and its Magdalene laundry remained at 111 West Raymond Street until the mid-1950s. The complex last appeared in the 1955 city directory. It was later demolished. Recent research did not disclose how the institution operated during its last decades, though it continued to be a place where unwed, pregnant mothers were sent. With automated washing machines, all Magdalene laundries in the U.S. closed by the 1960s. In the 21st century, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd run women’s shelters, halfway houses, and job training centers.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.