Since the city’s founding, religious bodies have been active in philanthropy and voluntary service. Philanthropy and religion have always been interconnected. Religion is the core of the nonprofit sector and receives the largest share of charitable giving in the U.S. Congregations raise funds and care for those in need in their own congregations and the broader community.

The relationship between philanthropy and religion is a mutually supportive and interdependent one. As the source of philanthropic ideals and behaviors, religion plays an important role in the community life of Indianapolis. As the recipient of voluntary effort and financial support, religion benefits from the philanthropy of Indianapolis residents. As community institutions, religious congregations also provide a context for the expression of philanthropy and for voluntarism that benefits the city and its residents.

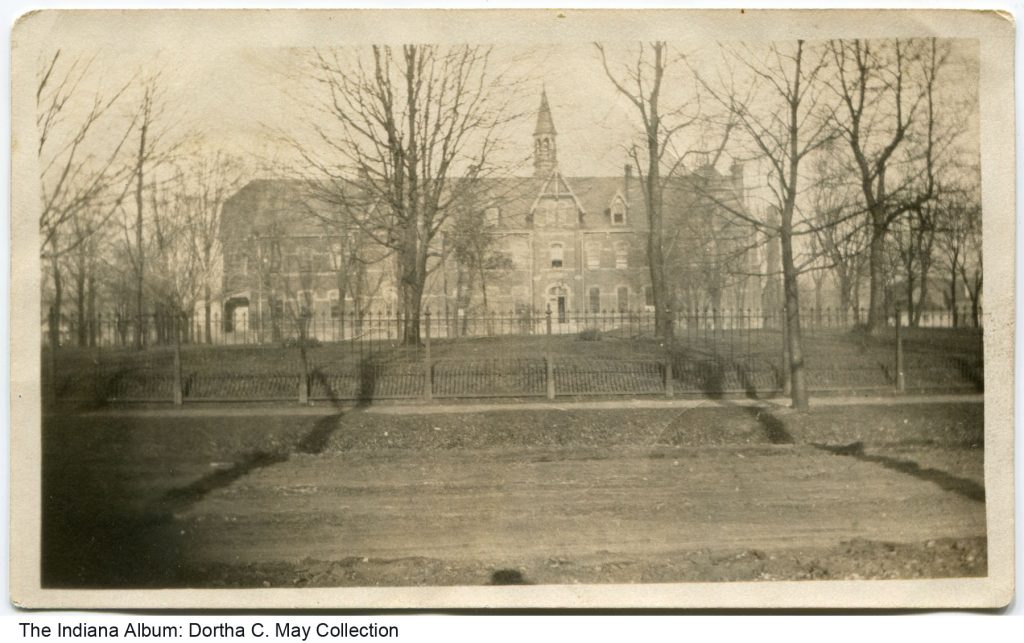

Churches, Sunday schools, and Bible and tract societies provided what Jacob Piatt Dunn Jr. called “the moral foundation” of the city. Much of early Indianapolis residents’ lives were rooted in the church, as religion provided a spiritual, moral, and social force in the community. By 1850, the Mile Square was dominated by religious structures and one estimate placed two-thirds of the city’s children in Sunday schools. Citizens recognized organized religion for its contributions to education, civic betterment, social interaction, and public morality. Religious teachings also undergirded attitudes toward poor relief and how philanthropy and public assistance should be balanced.

It is impossible to calculate precisely how much giving and volunteering are motivated by the religious convictions people hold. Scholars consistently find measures of religion as some of the strongest predictors of charitable giving. Approximately one-third of individual giving nationally goes to religion, with significant additional giving to faith-based schools, universities, hospitals, social services, and relief and development organizations. Values and faith, moreover, are the most powerful predictors of volunteering.

While congregations gather in churches, temples, synagogues, or mosques, religious philanthropy is also carried out by faith-based organizations whose public service is shaped by religious principles and experiences. , founded in 1883 as “an asylum for orphans and aged people.” The began in 1889, an example of a faith-based organization that is both an evangelical movement and a social service agency. Leaders of the founded the Open Door in 1893 to minister and shelter the city’s homeless. Religiously based philanthropies in the city range from comprehensive agencies like the (Protestant) , , and the , to more focused operations such as the , a ministry to victims of AIDS.

Religion inspired the creation of agencies that evolved into secular philanthropies. The (1876-2001) began as the General German Protestant Orphan Home, founded in part by the German Zion Evangelical Church (later Zion United Church of Christ). The (1876-1993), a Christian women’s group, started in 1876 to bring flowers to hospital patients and later sponsored a tuberculosis sanitarium, a children’s hospital, and the state’s first school of nursing. The was established in 1975 by the Episcopal Diocese of Indianapolis as a domestic violence shelter for women. Religiously motivated leaders opened in 1980 to distribute food to charities that feed the hungry.

The personal religious convictions of pharmaceutical executives and philanthropists , , and guided the development of the foundation that bears the family name. From its founding in 1937, has pursued grantmaking in the areas of community, education, and religion. Although direct grants to religious organizations and for religious research have rarely exceeded 25 percent of any year’s grants, the founders’ philanthropic interests, which drove the Endowment’s policies, were fundamentally religious in orientation.

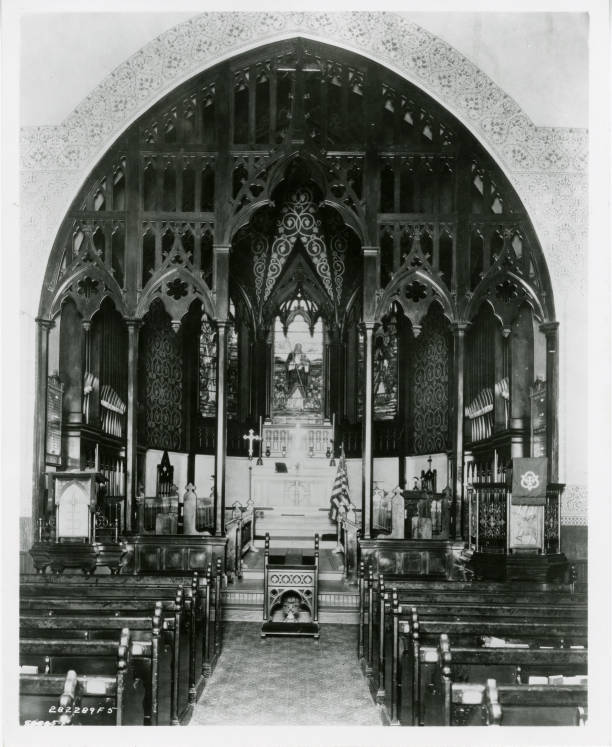

Eli Lilly made many substantial gifts to programs and causes of the Episcopal church. From 1927 onward, he served as a vestryman at , a role in which he took his duties seriously, to the point of personally cleaning out the church’s furnace room during his term in the 1950s as the junior warden in charge of church property. For the rest of his life, he shaped the programs of the Endowment to find and support “character education.” Thus, many grants made by the Endowment to this day are premised on a belief that better communities are made by enhancing individual character through educational settings suffused with religious and spiritual values.

Indianapolis has been the site of periodic debates over how to organize community benevolence. Religious convictions and precepts lie behind many of the positions concerned persons take in that debate. The spillover societal benefits of religious activity can be seen throughout the city’s history. Second Presbyterian and Westminster Presbyterian churches, for example, have cooperated in a ministry of service—across lines of class, neighborhood, and race—to the residents of the near eastside neighborhood in which Westminster is located. Through this partnership, persons unable to afford counsel may receive free legal advice, an elementary school student has a place to go after school, and persons learning to read are tutored.

African American congregations have taken on the ministry of relating to individuals confined in Indiana Women’s Prison and to ex-offenders in the transition to life after prison. Between 1982 and 2007, the sponsored the that brought major thinkers, authors, and performing artists to Indianapolis.

Congregational facilities also serve philanthropic ends as when Alcoholics Anonymous and ALANON chapters and other support groups meet there. After-school programs, aging adult daycare programs, and feeding programs for hungry and poor persons are increasingly prevalent in Indianapolis congregations. Countless , preschool, and mother’s- morning-out programs meet in churches, as do Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops. Bethlehem Lutheran Church houses the Neighborhood Association and works with local groups to assist in neighborhood redevelopment. and churches offer extensive athletic and recreational programs for city and neighborhood youths, as do other congregations.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.