The first pharmacy practitioner in what would become Indianapolis was likely an indigenous inhabitant who compounded medications from native plants. With the pioneer settlers of the 1820s came patent medicines and home remedies. The mid-19th century brought apothecaries whose only prerequisite to practicing the trade was sufficient business capital. Some practitioners trained by apprenticeship, but formal professional education was not yet unavailable.

Apothecaries, which also stocked paint, glass, lumber, dyes, and tobacco to supplement meager prescription compounding incomes, became known as drugstores. By 1840, Indianapolis had a drugstore on almost every corner. Noteworthy pharmacy practitioners of the 19th century were and . Louis and Julius Haag founded in 1876, and John A. Hook founded the Indianapolis retail pharmacy chain of in 1900.

The average turn-of-the-century pharmacy stocked 350 to 400 tinctures, syrups, elixirs, fluid extracts, emulsions, powders, solutions, narcotics, chemicals, and herbs. The pharmacist served as the neighborhood chemist who could compound elegant prescriptions, soft drinks, perfumes, shoe polish, furniture waxes, inks, and cosmetics. Unfortunately, many foodstuffs and drug products of the day contained contaminants and dangerous ingredients. Inaccurate labeling and exaggerated claims of superior healing powers characterized patent medicines.

In the 1870s, surrounding states adopted pharmacy practice acts to restrict sales of patent medicines and protect the public from untrained pharmacy practitioners. Indiana had no such law, and patent medicine hawkers moved here in droves. To address this issue, 200 pharmacists met in Indianapolis on May 9, 1882, and established the Indiana Pharmacists Association (IPA) to provide a professional forum and promote pharmacy licensure. Four years later, in 1886, Hurty, Lilly, Joseph Perry, and Arthur Timberlake organized the Indianapolis Association of Retail Druggists for a similar purpose.

By 1899, the legislature established a Board of Pharmacy and required one year of apprenticeship for licensure. The Indiana Board of Pharmacy regulations required in 1907 that an applicant for licensure pass a written examination. Regulations were adjusted again in 1911 to lengthen the pharmacy program to two sessions of 36 weeks each.

Pharmacy education in Indianapolis began in April 1904, when John Gertler organized the pharmacy department of Winona Technical Institute at the site of the former United States Arsenal and the current . The program consisted of two sessions of 26 weeks each leading to the Ph.G. degree (Pharmacy Graduate). Economic hardship resulted in the dissolution of the Winona Institute and the incorporated the pharmacy department for a time. In December 1914, a board of prominent citizens chartered the Indianapolis College of Pharmacy (ICP). The program included two sessions of 32 weeks each.

In 1924, the ICP bought the Indiana Veterinary College grounds on East Market Street, where it remained for 25 years. The program changed to a three-year course in 1925, and if a student wished to attend an extra ten weeks of classes, they would receive a Ph.C. degree (Pharmaceutical Chemist). The college’s curriculum changed again in 1930 when Indiana law required a four-year course of training. The addition of liberal arts classes to the professional curriculum upgraded the program, and graduates received a Bachelor of Science degree. Pharmacy regulations changed in 1932, adding one year of internship to the didactic education.

The onset of placed additional demands on the profession as the Pharmacy Corps drafted pharmacists. The ICP adapted to create accelerated programs that condensed a four-year curriculum into three years. In the late 1930s, independent colleges of pharmacy sought merger with larger institutions due to liberal arts course requirements. On October 13, 1945, the ICP merged with to become the Butler University College of Pharmacy (BUCOP).

Medical advancements of the late 1930s produced more potent but dangerous medications. Amendments to the federal Food and Drug Law in 1941 required a physician’s prescription for the sale of dangerous and addictive drugs, a practice that established pharmacist control and distribution of restricted classes of drugs. Large pharmaceutical firms produced more drug products in the late 1940s and 1950s, so the emphasis of community pharmacy practice shifted from compounding drug dosages to the accurate and safe dispensing of manufactured products. In 1952, amendments to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act required physician authorization of prescription refills, restricted dangerous drugs to prescription status only, and created an over-the-counter class of drugs.

The importance of merchandising increased as community pharmacy evolved into a retail business. In 1953, 425 independently owned pharmacies served the city, but competition from supermarkets and the chain pharmacies of Haag Drugs and Hook’s Drugs began to deplete their numbers. Pharmacy chains purchased many independent operations, with the previous owners electing to continue their practice as employees of the chain. In 1950, 90 percent of pharmacists were independent store owners. Forty years later most practitioners were employee pharmacists. Of the licensed pharmacies in in 1993 over 208 were chain or corporately owned pharmacy operations. By 2020, only about 20 percent of Indianapolis pharmacies were independently owned.

Since its inception, hospital pharmacy has received little regulatory attention. A hospitalized patient in the early 20th century received drugs from a “drug room” commonly staffed by a nurse. Local hospitals, however, reported the presence of pharmacy services as early as 1915 to 1920. Hospital practice was similar to community practice in that compounding prescriptions commanded much of the pharmacist’s attention and effort. In 1946, Indiana passed the Hospital Pharmacy Licensing Act to provide standards for facilities, drug storage and preparation, and uniform labeling of drugs in hospitals. Pharmaceutical science developed injectable medications and perfected intravenous fluid therapies, and hospital practice included the control and preparation of these therapies. Hospital practitioners needed a forum to address their unique practice and chartered the Indiana Society of Hospital Pharmacists in 1952.

In 1960, the Butler University College of Pharmacy instituted a mandatory five-year program in response to increasing practice demands and accreditation requirements. Local pharmacists initiated drug abuse education and poison prevention programs in the 1960s. They also developed patient medication recording systems to prevent allergic reactions and avoid interactions between drugs. In the late 1960s, hospital pharmacists introduced the practice of clinical pharmacy, wherein the pharmacist functions as a therapeutic advisor. Hospital-based drug information services and drug dosing services focused on individualizing drug therapy for specific patients. In community pharmacy, many practitioners exercise this therapeutic advisory capacity by providing patient education with each prescription. Butler’s program incorporated patient education courses into the curriculum.

The profession also experienced a gender shift during this era. In March of 1969, 29.5 percent of the Butler pharmacy class was female. By 1978, 58 percent of the freshman pharmacy class was female. That figure rose to 70 percent in 1992, and by 2020, women made up a full three-quarters of the freshman pharmacy class.

Technological advances in the 1970s and 1980s produced drugs that exhibited greater disease specificity and generated a variety of drug administration devices that permitted home delivery of intensive therapies such as intravenous nutrition, cancer chemotherapy, and pain management. Computers provided rapid access to drug information and alerted the pharmacist to potential drug therapy problems.

In the 1990s, increasing societal demands required highly trained pharmacists who were patient-oriented and responsible for the outcomes of drug therapy. Thus, in 1990, the Butler program initiated an optional six-year Doctor of Pharmacy program. By 2020, the college was still offering a six-year path, but it also included specialized tracks such as patient care research.

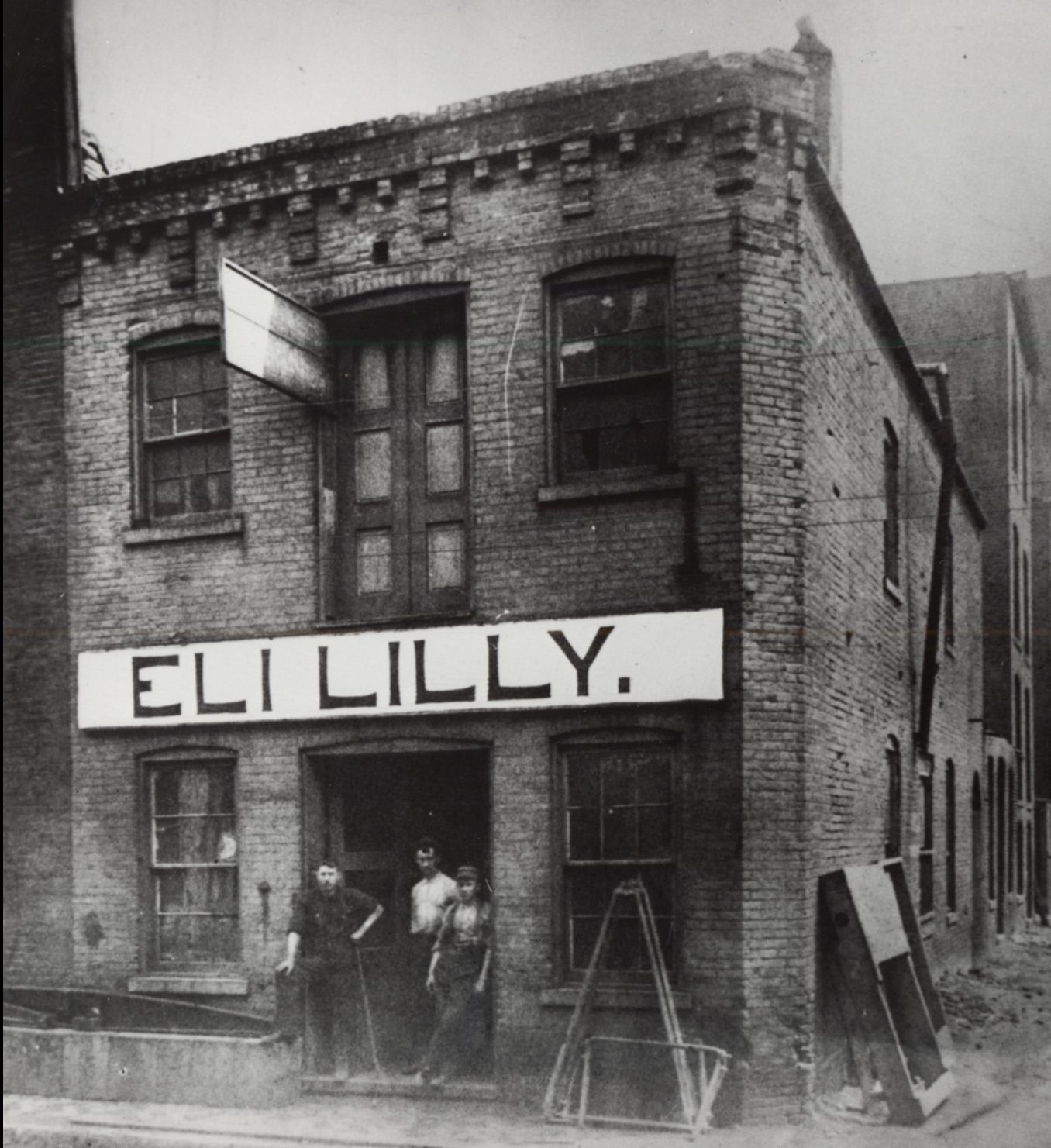

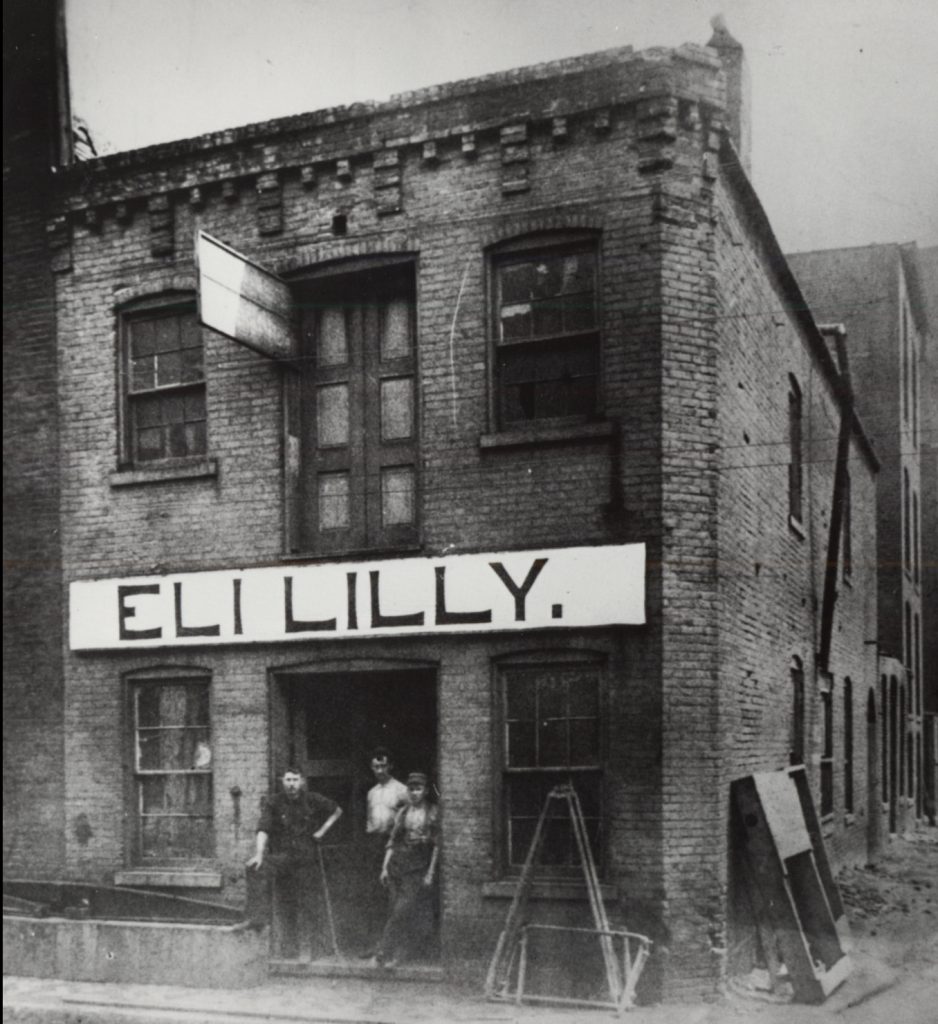

By the mid-2000s, Indianapolis quickly became a hub for pharmacy-related businesses. Already the home of Eli Lilly and Roche Diagnostics, companies with large distribution centers such as Medco (now Express Scripts) and WellPoint (now ) were drawn to the city for its relatively low cost of business, its central location with a major airport nearby, and its large pharmacist and technician workforce (Butler and Purdue Universities graduated 300 pharmacy students in 2008).

The North American headquarters at the northeast corner of Indianapolis has emerged as one of the largest global biotech companies. Its acquisition of biotechnology giant Genentech has allowed Roche to become one of the leading developers of targeted cancer treatments and differentiated medicines. Roche has seen tremendous potential in developing drugs for use in oncology, immunology, ophthalmology, infectious diseases, and neuroscience. Eight of Roche Pharmaceutical’s ten top-selling medicines are developed using the biotechnology and biopharmaceutical innovations Genentech brought to the company. These innovations account for more than 70 percent of Roche’s pharmaceutical sales.

Eli Lilly and Company, located in the heart of downtown Indianapolis has made similar inroads as Roche in the biopharmaceutical arena. Its research and development department continues to target drug development in its areas of expertise which include diabetes, neuroscience, cardiovascular diseases, and oncology. Eli Lilly’s biggest revenue generator continues to be its therapies for diabetes management.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.