Professional nursing in the United States dates back to the last quarter of the 19th century. Before that time religious orders provided nursing care in and Protestant hospitals (see . Untrained, and often unscrupulous, former patients functioned as nurses in most municipal hospitals. American women became aware of the atrocious conditions in city hospitals and the need for trained nurses through the work of Englishwoman Florence Nightingale. During the women demonstrated their ability to nurse the sick and the wounded. The movement to create professional nurse training schools, however, lost momentum until after the Civil War. The first nurse training school in the United States did not open until 1873.

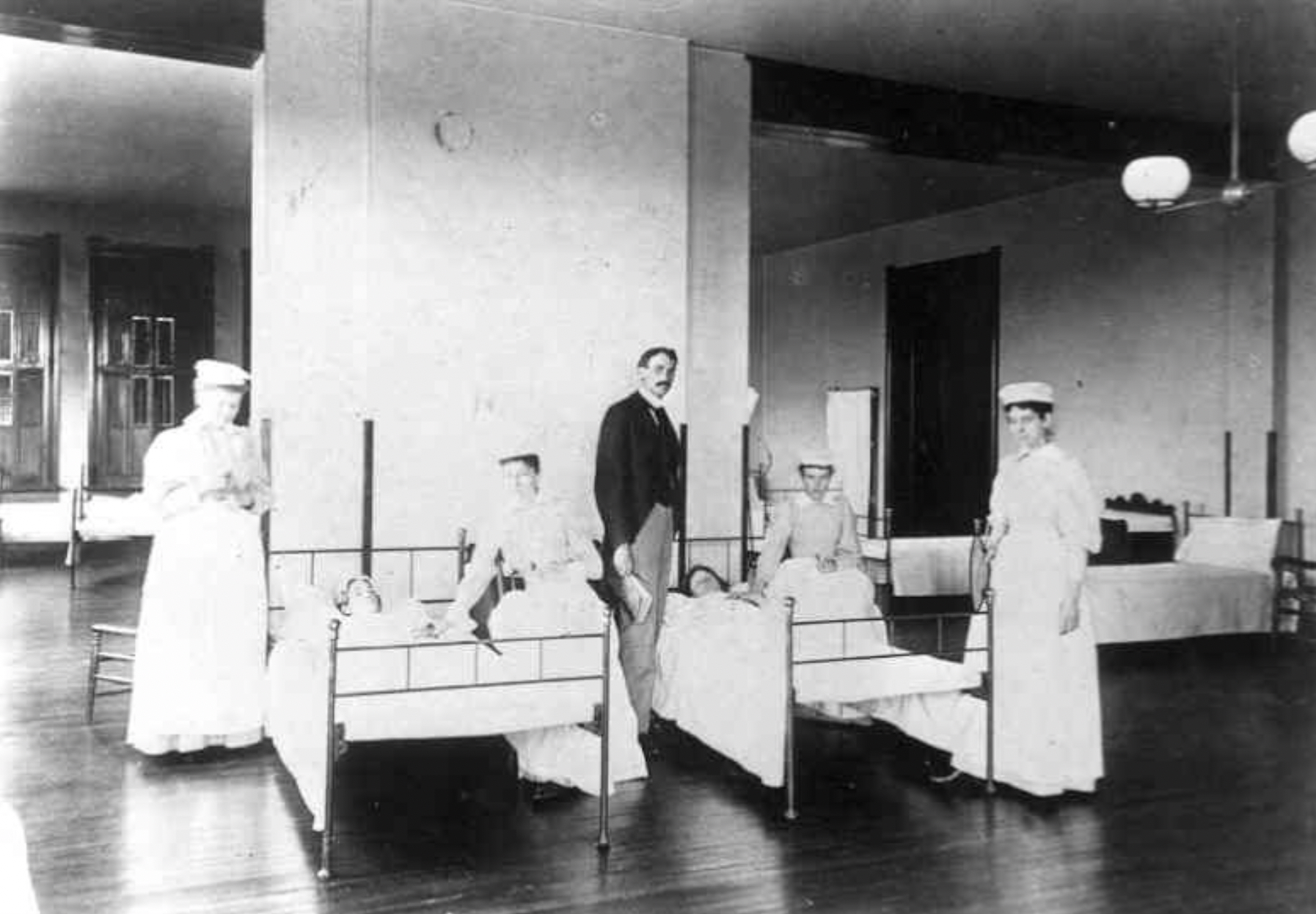

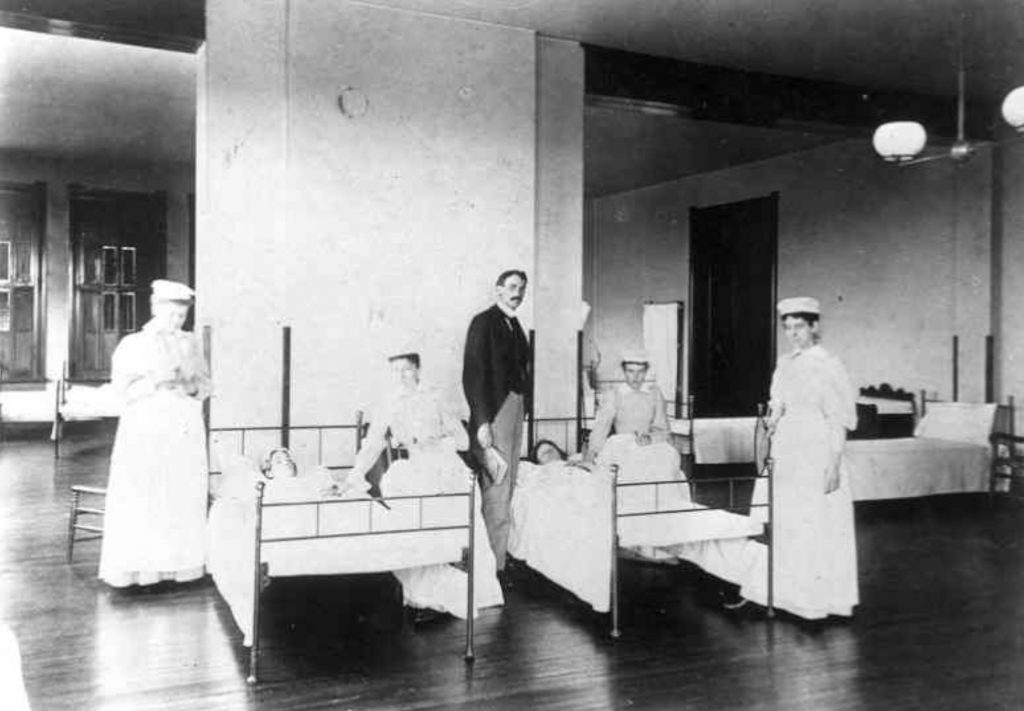

Indianapolis played a leading role in the development of professional nursing within the state. In 1883 the first nurse training program opened in the city. The Flower Mission Training School for Nurses (later the School of Nursing), which was opened by the , supplied nursing care for the Indianapolis City Hospital (now Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital) and provided nursing care for the community through its system of district nursing. Nursing students from the hospital also worked in private duty practice, providing nursing care for patients in their homes. During this period nursing required long hours and offered little pay.

As hospitals grew and developed in Indianapolis, so did the number of nurse training schools. opened its program in 1896; Protestant Deaconess in 1899; Methodist in 1908; and the Indiana University Training School for Nurses in Indianapolis (now Indiana University School of Nursing) in 1914. As was common in other parts of the United States, Black women were denied admission to nurse training schools well into the 20th century. In the 1910s Black women trained at Indianapolis’ two Black hospitals, the and . These hospitals closed in the 1920s, however, and Wishard Hospital’s School of Nursing began to accept Black women into its program. Not until 1953 did the first Black woman graduate from Indiana University School of Nursing.

The formation of professional nursing associations and nurse registries (organizations providing the names of nurses for employment) closely followed the establishment of nurse training schools. In 1885 local nurses formed the “Nightingales of Indianapolis,” which functioned as a nurse registry. The Marion County Nurses Association formed in the early 20th century. In 1904 the Indiana State Nurses Association was officially incorporated with headquarters in Indianapolis. That group played a leading role in formulating standards for the profession, establishing a registry for nurses, and developing a standard nursing school curriculum. By 1913 a bill passed the Indiana state legislature requiring a minimum of three years of training for nurses.

Leaders in nursing education stressed the benefit of baccalaureate degree nursing programs over diploma programs. The 1923 Winslow-Goldmark report, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, substantiated this view The report’s authors urged that nursing schools affiliate with institutions of higher learning and that universities improve postgraduate education for nurses. The Indiana University School of Nursing already was affiliated with a university. In the 1930s Wishard Hospital’s program and program respectively affiliated with and DePauw University. The need for qualified nursing instructors led Indiana University in 1932 to offer nursing education courses. A doctorate in nursing at Indiana University, however, was not available until 1978.

In 1922, six student nurses at Indiana University School of Nursing in Indianapolis founded , the first national nursing honor society. The organization’s national headquarters opened in Indianapolis in 1974. Today, that association is an international society that actively supports nursing research and grants nursing scholarships.

Originally the focus was on hospital and private duty nursing. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, public health nursing became increasingly important. In 1890 Indianapolis employed a public health nurse to care for the poor of the city. Yet, these nurses had no specialized training. In 1912 local nurses formed the Indianapolis Visiting Nurse Association (renamed the Visiting Nurse Association of Indianapolis in 1947) to address the special needs of these nurses. Finally, in 1917, under the leadership of Abbie Hunt Bryce (who had served as the first superintendent of nurses at City Hospital and was instrumental in forming an Indianapolis Visiting Nurse Section), the Indiana State Nurses Association formed a public health nursing section.

The official recognition of public health nursing as a separate nursing specialty led private duty nurses to lobby for similar recognition. Frances M. Ott, a graduate of Wishard School of Nursing, was one of the leading advocates for the establishment of a private duty section of the state association. In 1920 the state association formed a private duty section and fought for the establishment of a 12-hour work day (rather than a 20-hour one) for nurses.

In 1939, the Indiana State Nurses Association established an industrial section. The development of this specialty coincided with the growth of industrial jobs and interest in occupational and industrial diseases in the 1930s.

The world wars gave impetus to the profession, although the hurt nursing. brought a decline in the number of nursing students, and many Indianapolis nurses were recruited through the Red Cross. Several Indianapolis nurses served at . In 1921 the state association undertook a nurse recruitment campaign to meet the demand for nurses which resulted from increasing numbers of hospital patients.

The Great Depression, however, hit the nursing profession hard. Earlier campaigns had increased the number of nurses, but the number of jobs declined during the 1930s. Although some nurse training schools throughout the state closed, the Indianapolis nurse training schools remained open.

The outbreak of brought an increased need for nurses. In July, 1942, the U.S. Congress passed the Bolton Act to prepare nurses in large numbers for the armed services. Indiana University also began an accelerated nurse training program to allay the shortage. Although these efforts helped increase the number of nurses, Indianapolis suffered from a severe nursing shortage after the war. Edward F. Gallahue, the president of the American States Insurance Company, provided a solution to the nurse shortage by aggressively recruiting young people—particularly Methodist youth—through a year-round recruitment campaign, which became known as the Indiana Plan (or ). This effort was aided by the Indianapolis , which established a nurse enrollment week, and the local newspapers, which sponsored a public awareness campaign.

During the 1940s, the Indiana State Nurses Association realized the need for auxiliary personnel to assist nurses: by 1947 it published regulations for trained attendants and formed a practical nurses association in 1949. In 1950 a school, operated under the public school system, opened in Indianapolis to train practical nurses.

In the 1940s and 1950s nurses became increasingly specialized—surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry all had specially trained nurses. Whereas nurses once performed more menial tasks, today they have assumed greatly increased responsibilities, some of which traditionally belonged to physicians. Also, nursing was dominated by women in the 1940s; only 2.3 percent of nurses were male. Today, an increasing number of nurses are male (approximately 5 percent), but the profession remains predominantly female one.

In the 1960s, the nursing shortage continued, despite federal subsidies to nurse education. In the mid-1960s a survey of nursing resources in the Indianapolis metropolitan area was conducted by the consulting firm of Booz, Allen, and Hamilton at the request of the Indianapolis Hospital Development Association. This report revealed that the demand for nurses would soon exceed the supply if existing nursing programs were not expanded and others were not created. It also urged that existing programs be improved and suggested that nursing schools affiliate with universities. The decision of Methodist Hospital in 1966 to close its diploma nursing program and of St. Vincent Hospital to phase out its diploma program magnified the potential nursing shortage. As a result of the report, (which had been affiliated with St. Vincent) began a baccalaureate degree program in nursing using St. Vincent’s clinical resources. To increase the supply of nurses, Indiana University established an associate degree in 1965.

In 1980, Wishard Memorial Hospital closed its nursing program. With DePauw University’s decision to close its nursing program in 1993, Indianapolis had only two baccalaureate degree nursing programs in the city—Indiana University School of Nursing and Marian College School of Nursing. The demand for nurses within Indianapolis remained high in the early 1990s.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.