On April 16, 1920, the Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana, Indianapolis Branch, disbanded and established a League of Women Voters of Indianapolis (LWV) in its place, carrying the members of the Franchise League on its roster for six months. These actions followed similar ones by the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association and the state Woman’s Franchise League since the primary purpose of those organizations, securing the vote for women, was certain of accomplishment.

The new organization had as its purposes “fostering education in citizenship and supporting needed legislation.” The league’s mission remains largely unchanged with its stated goal of “making democracy work.” It is a nonpartisan organization devoted to promoting informed and active citizen participation in government.

In its earliest days, the league supported the “50-50 law,” designed to give men and women equal representation in political parties. A modification of the bill passed in 1925, which provided for the appointment of a vice chairman of the opposite sex by elected officials, instead of by voters. In the early 1920s, under the leadership of , the LWV of Indianapolis conducted classes on citizenship, later establishing citizenship courses at Butler University in 1926 and 1927. In 1933, it advocated for a permanent registration law that passed in 1933.

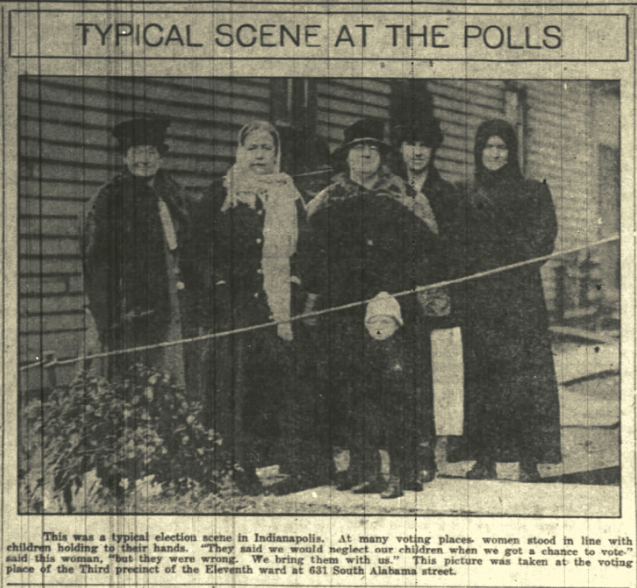

The Indianapolis league also ran intensive “Get-Out-the-Vote” campaigns, biennial voter registration drives, and candidate forums. Candidate questionnaires were reprinted in the newspapers in advance of each election. Later, during the Great Depression, the organization worked to educate its members and the public about the cost of government and began a 20-year campaign to support the merit system and eliminate patronage.

Success came more swiftly when reforms concentrated on issues traditionally associated with women—for example, strengthening the system in the 1930s. The study of the juvenile court, begun in 1931, led to successful efforts in the 1935 General Assembly to strengthen the Probation Department and clarify the law establishing the Juvenile Court of Marion County. Finding that the administration of the court was inadequate, in 1938 the LWV helped to form the Marion County Bi-Partisan Juvenile Court Committee to arouse citizen interest in attracting able candidates.

In the 1940s, League members surveyed city government and attached themselves individually to each of the 15 departments, often being appointed to specific advisory committees.

Connecting with the public in innovative ways has always been important to the League of Women Voters. In 1941, it held voting machine demonstrations downtown and continued this activity at various locations for three decades, except for a brief period in 1942 when the county commissioners would not allow them the use of a machine. In 1946 the first monthly radio show hosted by League members aired on WISH. In 1952 under the leadership of Elaine Thomas, the LWV began to use television, first for voting machine demonstrations and eventually for candidate forums.

Not all League advocacy efforts have been successful, and some have been controversial. In the 1950s, controversy resulted from the national league’s position opposing the Bricker Amendment (the collective name of a series of constitutional amendments aimed at limiting presidential powers) and efforts to have flags of the United Nations displayed in the plaza.

Working throughout the 1950s toward consolidation of city and county services, in 1959 the LWV began publication of , a booklet designed to help citizens understand their local government so they could work to change it. In the 1960s, under the leadership of Jean Tyler, the League conducted massive voter registration drives and educational campaigns ahead of the 1963, 1964, and 1967 elections.

Finally, in 1969, the General Assembly passed the Unigov legislation consolidating city and county government and embodying many of the reforms the League had long sought. During the 1970s, the LWV worked tirelessly to educate the public on the intricacies of local government, especially after the creation of in 1969.

The league’s civic education role also entailed advocacy. It routinely monitored pending ordinances and legislation, attended committee meetings of the (following Unigov), studied policy needs, proposed policy solutions, and educated the public on needed reforms.

The organization published its first edition of the in 1980, as a reference for Marion County voters and its elected officials. It has become an important resource for understanding Indianapolis’ local government, and LWV has published revised, updated editions to incorporate and explain changes.

In more recent decades, the league has supported efforts to make the voting process more convenient and accessible. In the early 2000s, the LWV hosted public events and community conversations about voting needs in Marion County. For example, its members wrote letters to the editor of the and provided testimony to the in support of satellite voting.

In 2005, the Indiana General Assembly passed one of the nation’s first voter I.D. laws. In November of 2007, LWV of Indianapolis signed on to an amicus brief in support of the plaintiff’s argument that the law was unconstitutional. Plaintiffs argued their case before the Supreme Court of the United States on January 9, 2008 (), but the law was upheld in a 6-3 decision.

In June of the same year, the League filed a complaint in the Marion Superior Court against the Marion County Election Board. After several appeals, oral arguments in League of Women Voters v. Rokita were presented in the Indiana Supreme Court on March 4, 2010. In June, the Court issued its decision affirming the decision of the trial court granting the defendant’s motion to dismiss, leaving Indiana’s voter I.D. law to stand.

Candidate forums, and to lesser extent guides, have remained a staple of League activity through the early 2000s. Diminished media attention and candidate participation in forums led the LWV to launch the Vote411.org online voter resource and candidate guide, in 2018.

The League of Women Voters continues to dedicate considerable resources to voter education and empowerment. In a break with the longstanding tradition of only training its members on how to register voters, the organization began conducting training for the public in 2018. It also maintains publications on how to vote in Marion County and a local directory of government officials.

Until the 1980s, LWV members were predominantly white, college-educated wives of business and professional men, but the leadership has sought to recruit women (and, since 1974, men) from all walks of life. As of 2018, under the bylaws of the national organization, the Indianapolis league has welcomed members from all U.S. residents age 16 and older.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.