The Indiana Crossdresser Society (IXE) served gender non-conforming Hoosiers by providing social opportunities and support to individuals who struggled with gender identity and challenging instances of discrimination. According to the International Foundation for Gender Education in Wayland, Massachusetts, as many as 20,000 Indianapolis residents identified as gender non-conforming at the time of the organization’s founding in the late 1980s. The term captured a broad range of individuals from transvestites, who simply wanted to wear women’s undergarments, to transexual persons, who perceived themselves as members of the opposite sex. It included those who identified as “cross-dressers,” male/female “impersonators,” and, in modern terminology, “transgender,” which refers to all individuals with identities that cross over, move between, or otherwise challenge socially constructed borders between genders.

Prior to the formation of IXE, some Indianapolis area gender non-conforming individuals attended meetings held by Cross-Port, a group that provided support and social opportunities for gender non-conforming people in Cincinnati. By early 1987, they formed a similar group in Indianapolis. It initially was called Iota Chi Sigma before becoming known as the Indiana Crossdresser Society. About 13 people attended its first meeting.

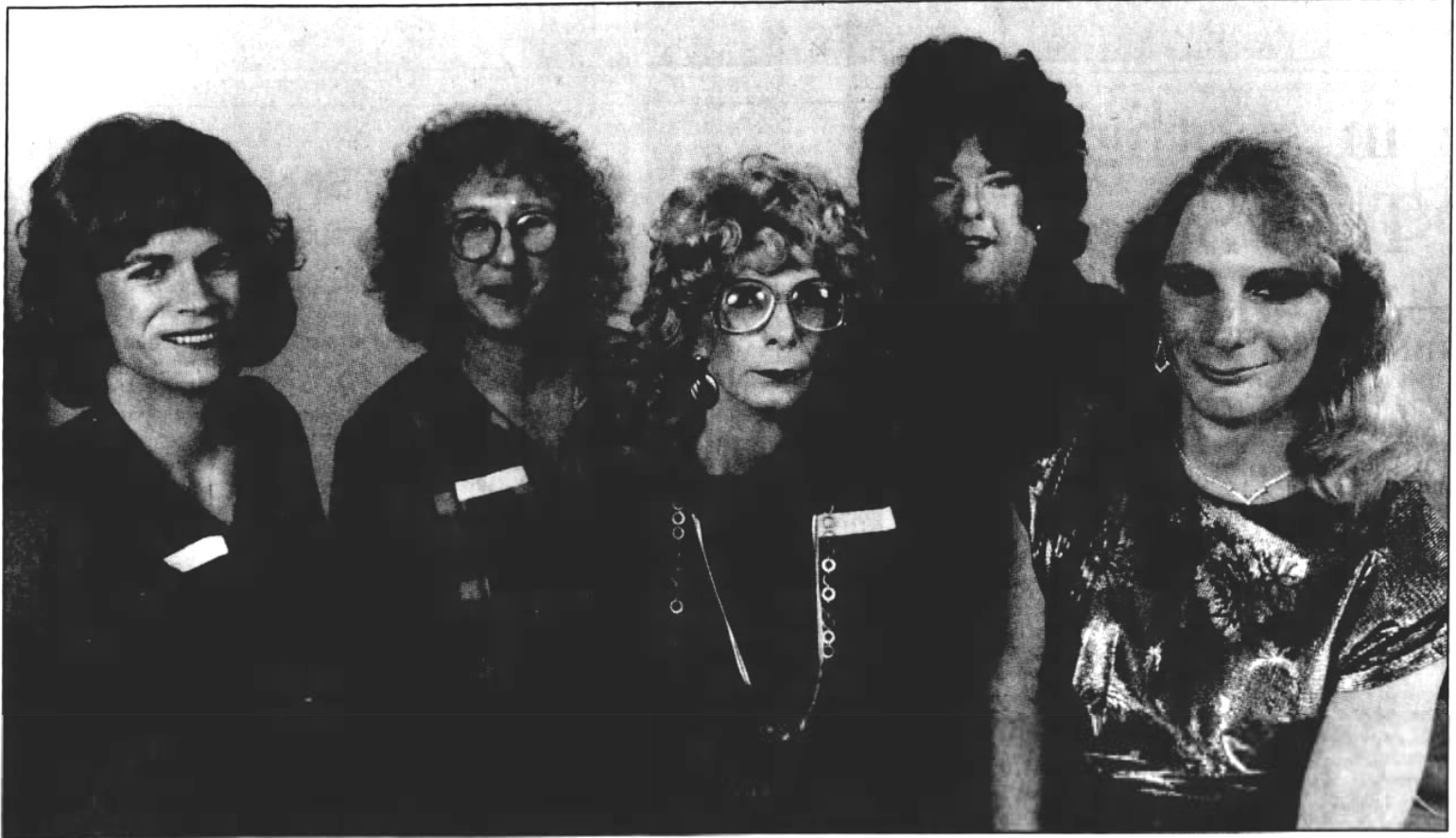

After this first gathering, IXE met the first Thursday of every month at 21 Club on Talbott Street. Within a year, IXE meetings had larger attendance than Cross-Port, and, by 1989, IXE had over 100 members residing in the tri-state area—which included Kentucky—forging a social network of support for the marginalized community. Most members were heterosexual men experiencing “gender conflict.” They came from a variety of professions, including carpentry, business, and law enforcement. Approximately 30 members met monthly to socialize at a west-side apartment clubhouse, and many of them brought their spouses. At one meeting, cosmetologists gave members makeup tips. At another, police officers advised them on how to avoid a “scene” in public.

In 1989, IXE joined Justice, Inc., a statewide umbrella organization for support and activist groups working in and with the gay/lesbian community. Members of the community experienced police harassment and surveillance, and prejudice may have affected the way law enforcement approached the homicides of gay men. This partnership among support, activist, and lobbying organizations proved critical to challenging these types of discrimination.

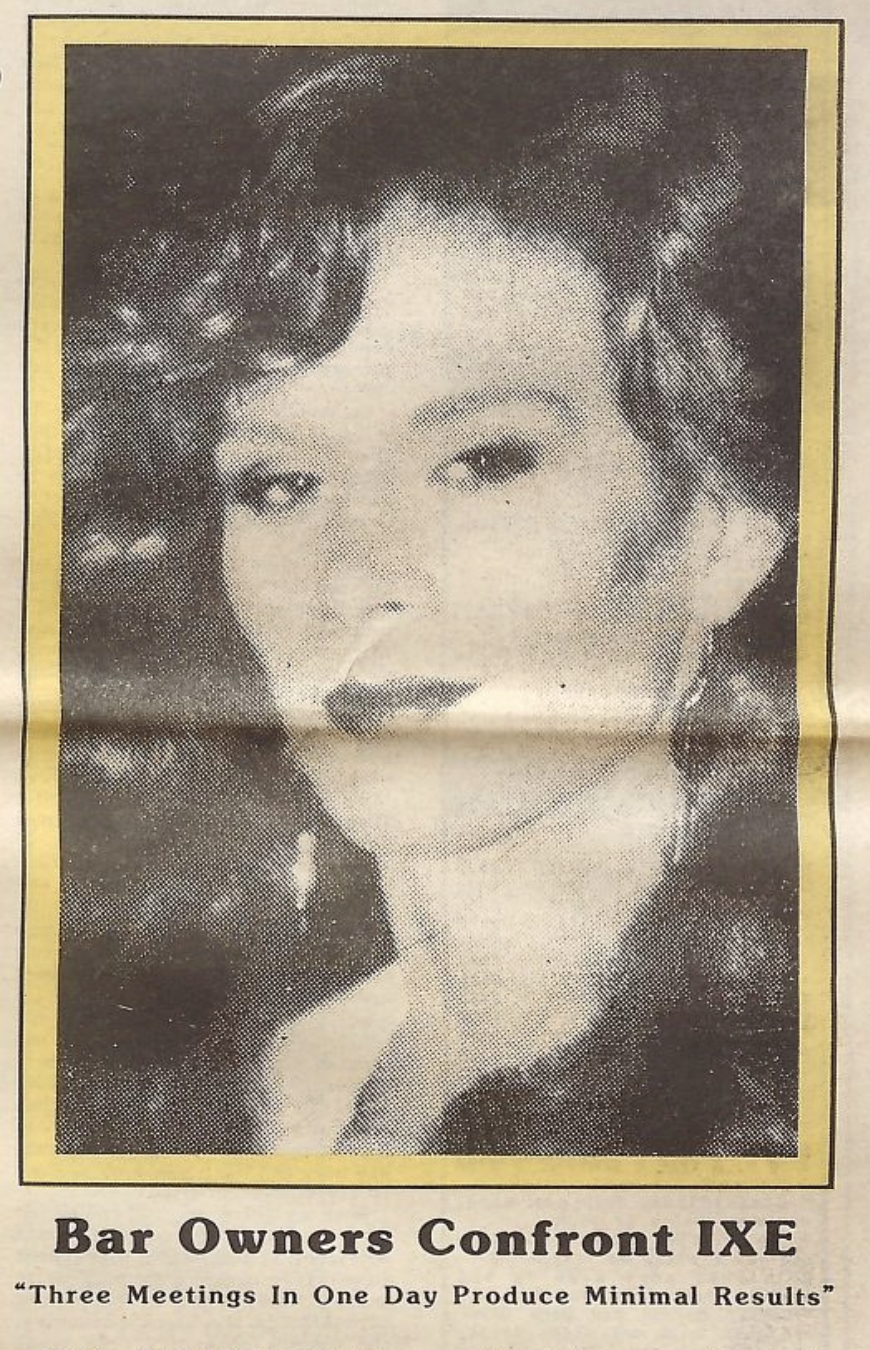

In some cases, cross-dressers and transgender individuals faced discrimination from other groups in the LGBTQ community. Gay bars afforded a degree of shelter as safe places to gather, but not everyone had the opportunity to patronize them. In 1989, instances increased in which bar owners refused to serve cross-dressing and transgender individuals because they did not meet dress codes, or their photo IDs did not “match” their faces. For example, Our Place, one of the largest gay bars in Indianapolis at 16th and Delaware streets, posted a dress code that blocked entry to “men wearing wigs, makeup or female clothing.” Such policies not only humiliated cross-dressing and transgender individuals but also sometimes resulted in their arrest. Individuals whom these policies targeted noted the dress code at Our Place proved counterproductive to the gains acquired since the beginning of the Pride movement to improve civil rights for the LGBTQ community. The Stonewall Uprising of 1969—protests that erupted in New York City after a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar—had sparked the movement. Gender non-conforming individuals stated that these policies sent a terrifyingly repressive message to the straight community.

Indiana Crossdresser Society initiated a series of meetings with the bar owners, excise police, and allies like Justice, Inc., and the . These meetings provided a starting point to exchange perspectives and to better understand the role of the excise police, whose mission was “to protect the morals and welfare of the people” of the state as they enforced liquor laws.

In September 1989, upon IXE’s request, Justice, Inc. surveyed parties involved in conflicts with bar owners and then hosted a workshop to resolve issues that emerged. This workshop provided an opportunity to discuss injustices that various groups experienced. Many voiced their anguish about discrimination within the lesbian community, against persons with AIDS, and along racial lines. At the center of the meeting, however, remained the exclusion of gender non-conforming individuals. IXE vice president Sharon Allan paralleled the trials of cross-dressers and drag queens to that of the gay community in prior years. These meetings, while contentious, led to the reversal of policies at some bars and helped open the door to acceptance for other gender non-conforming individuals in Indianapolis.

IXE members noted progress at the first large public at in 1990. People who staffed IXE’s booth reported feeling accepted, if not entirely understood. A feature that the published about IXE brought the gender non-conforming community out of the shadows in the mainstream media. The feature’s author noted public interest in receiving more information about IXE.

The group continued to grow in the 1990s, and it appeared in gender-related publications until at least 2005. Its members’ activism and willingness to facilitate discussion helped change public perceptions about gender non-conforming individuals and contributed to greater inclusivity within the LGBTQ community.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.