Photo info ...

Credit: H. J. Lewis via Wikimedia CommonsView Source

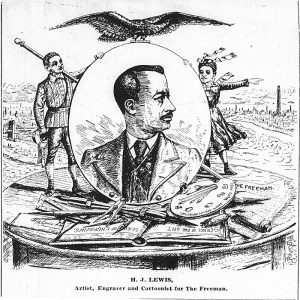

(ca. 1830s-Apr. 10, 1891). Henry Jackson Lewis was born enslaved near Water Valley, Mississippi in the late 1830s, although some sources place his birthdate as late as the 1850s. As an infant, he fell into a fire, which left him with a disabled left hand and blind in his left eye. Despite his disabilities, he taught himself to draw and eventually mastered the craft of engraving for newspapers. Working for the , Lewis is commonly known as the first African American editorial cartoonist.

When Lewis gained freedom in 1863, he volunteered to serve in the Union army during the Civil War with the Fourth United States Colored Heavy Artillery. In 1866, Corporal Lewis mustered out of the service at Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where he found work as a carpenter.

On March 14, 1872, one of Lewis’ first pencil drawings appeared in The Little Rock Daily Republican/The Morning Republican. By 1879, he was selling drawings to national publications. When Harper’s Weekly published six engravings credited to Lewis that year, news of his artistic ability spread across the country.

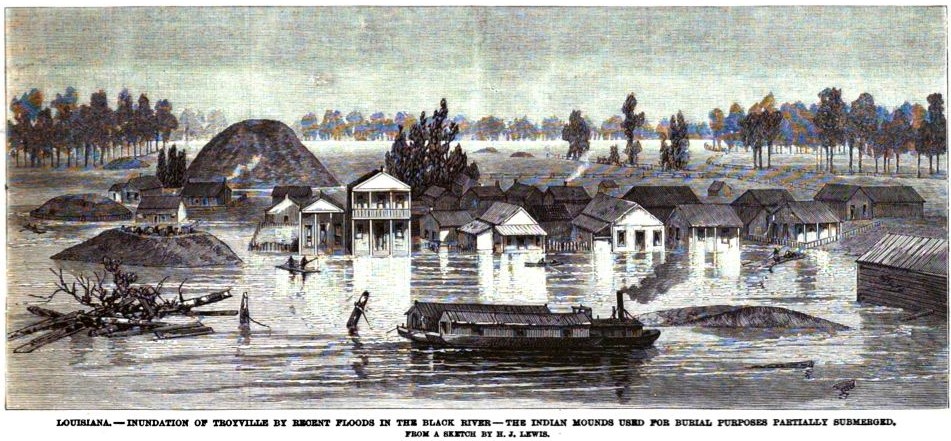

Late in 1882, Edward Palmer, an archaeologist, contracted Lewis to produce sketches for the Smithsonian’s “Mound Survey” of prehistoric Indigenous Peoples sites in eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, western Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana. These drawings helped to disprove the theory that the mounds were built by a “lost race” of non-Indigenous “Mound Builders,” although Lewis did not receive full credit for his work until 1990. His mound drawings reside in the Smithsonian National Anthropological Archives.

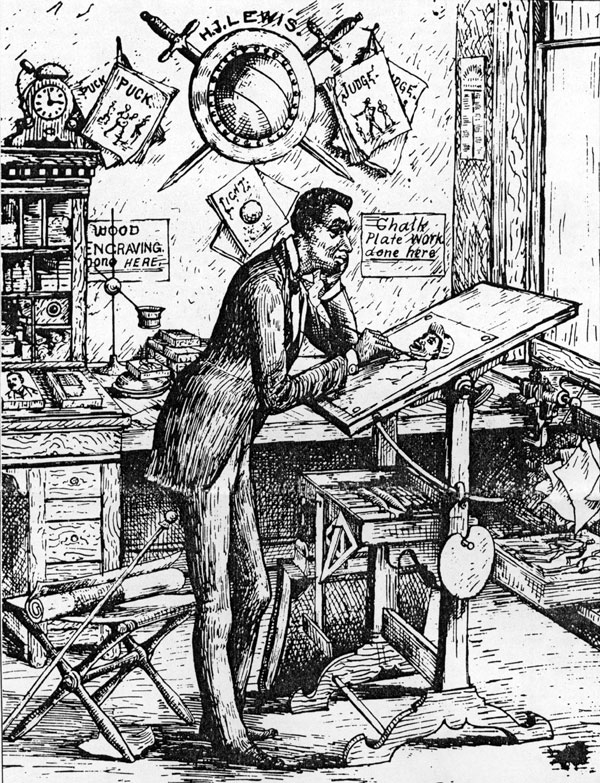

Around 1885, Lewis took a job as a porter for the Arkansas Gazette, where he learned artistic engraving techniques from its staff. In January 1889, Indianapolis Freeman editor Edward Elder Cooper brought Lewis to Indianapolis to work as the newspaper’s pictorial reporter, cartoonist, and engraver. In the 27 months that Lewis lived and worked in Indianapolis, the Freeman published close to 175 of Lewis’ editorial and political cartoons, caricatures, and illustrations.

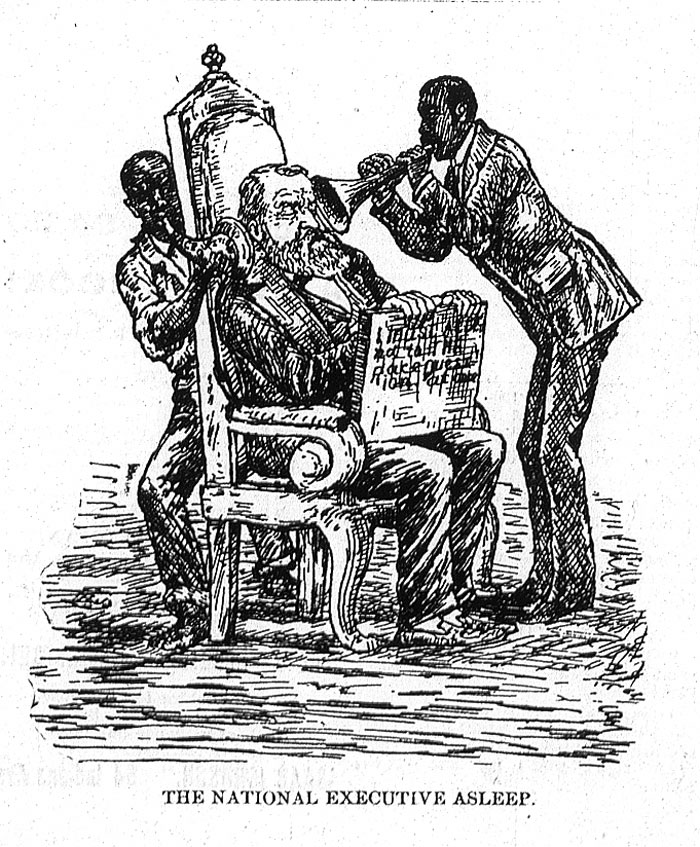

In contrast to the way whites depicted Blacks as lazy, poor, and uneducated, Lewis used his drawings to focus on themes of uplift, the existence of a higher economic and social Black class, and African American civil rights. His images protested violence, discrimination, and particularly lynching in southern states. A few images suggested strategies for resistance, and many of them documented the celebration of African American culture and values. His illustrations brought attention to the Freeman, which became known as “the Harper’s Weekly of the colored race.”

The most common theme of his Freeman cartoons, however, was a biting criticism of President and his Republican administration for failing to support job opportunities for Blacks and of politicians’ general refusal to acknowledge racism. On October 19, 1889, the Freeman published Lewis’ cartoon titled “The National Executive Asleep.” The depiction of Harrison, unconscious and sitting on a throne, as Black men blared bugles at him, sparked controversy.

Following the publication of the controversial cartoon, the Freeman no longer took such an oppositional stance to the Harrison administration, and an article that appeared in the Cleveland Gazette on November 9, 1889, announced that Lewis had “severed his connection” with the newspaper. After leaving the Freeman, Lewis worked out of his own studio on Washington Street in Indianapolis, selling his drawings to various publications.

The Freeman only published two more of his political cartoons, one in December 1890 and another in January 1891. On March 28, 1891, the newspaper published Lewis’s final work, an architectural drawing of St. Paul African American Episcopal Church in St. Louis, Missouri.

Two weeks later, after a 10-day bout of pneumonia, Lewis died in Indianapolis. He was survived by his wife and seven children. The oldest child, John W. Lewis became an artist and drew for the Freeman, , and .

In 1968, Lewis’ son Chester Arthur Lewis bequeathed the surviving 47 original ink-on-paper drawings, mostly unpublished editorial cartoons, to the Du Sable Museum of African American History in Chicago.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.