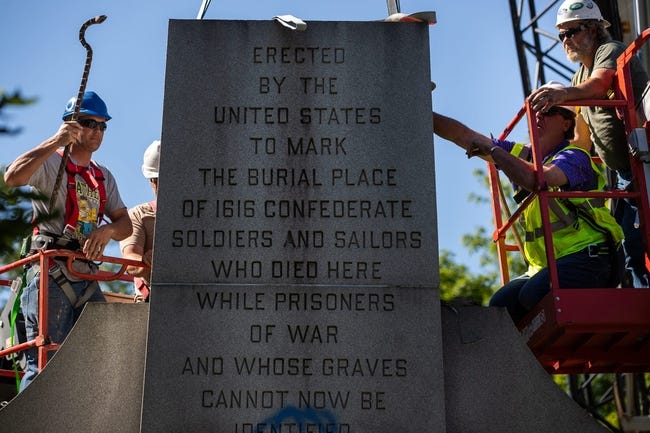

Upon its construction in 1910, a 35-foot monument marked the graves of 1,616 Confederate soldiers who died at , a Union prisoner-of-war camp in Indianapolis. It stood in , which had been established between the and South Street as the city’s first public cemetery in the 1820s. Those graves had not been well recognized to that point.

To accommodate the Confederate dead, originally buried in trenches at Camp Morton, the U.S. government purchased five sections of Greenlawn for their reinterment shortly after the conflict. Removal of the remains allowed the Camp Morton site to revert to its use as the . After reburial, wooden placards, painted with identification numbers that corresponded with names listed in the original, paper records were placed at the gravesites.

While more than 700 Union soldiers buried at Greenlawn were transferred to the then-new after it became a national cemetery in 1866, the Confederate dead remained at the old cemetery. Crown Hill’s designation as a national cemetery and this reinterment were part of the U.S. government program initiated to locate, move when necessary, and mark the graves of Union troops who died in the Civil War. The U.S. Congress made no such effort either to provide for or identify Confederate burial sites. Instead, Southern states with the help of Southern advocacy groups, such as the Daughters of the Confederacy, campaigned to recognize the graves of Confederate troops. This changed in February 1908. President Theodore Roosevelt voiced support for marking the graves of those former Confederate officers who reenlisted, served, and distinguished themselves fighting in the Spanish-American War.

Former Confederate army colonel William C. Oates, who served as a U.S. Army brigadier general during the Spanish-American War, set out to find places where Confederate soldiers should be memorialized. He toured Greenlawn to assess the viability of the government’s grave-marking effort in Indianapolis. Upon inspection of the soldiers’ burial records, some of which were missing and others of which were damaged in a fire, Oates suggested creating a single, mass grave marker with the names of the 1,616 soldiers engraved upon it rather than erecting hundreds of individual markers inscribed with the word “unknown.”

Oates volunteered to seek funds for the project. In May 1909, the federal government accepted Oates’ proposal and paid Van Arminge Granite Company of Boston, Massachusetts, $6,000 to design, manufacture, ship, and place the obelisk at Greenlawn. The announced in May 1910 that the “monument erected by the United States government to the memory of several hundred Confederate soldiers at Greenlawn Cemetery has been completed.” Among the names of the dead listed on the obelisk were at least 12 African Americans who died at the camp but who were not soldiers. They were the chattel property of Confederate enslavers with whom they were imprisoned.

Although supporters of the obelisk celebrated Memorial Day at Greenlawn in the years following, Indianapolis citizens abandoned the old cemetery in favor of Crown Hill. Much of what had been at Greenlawn disappeared, with many graves relocated to accommodate the construction of the Vandalia Railroad’s shop and roundhouse. Flooding from the White River washed away other tombs. By the late 1910s, little was left at the cemetery except for the Confederate monument located in “a remote corner of the old burying ground,” adjoining the Vandalia Railroad yards backed up “against a blackened fence and barn.”

In 1918, the Southern Club of Indianapolis, established in 1916 to celebrate and preserve Southern traditions and culture, became the official organizer of the Memorial Day event at the monument. Its members wanted to move the Confederate monument to a place that was “more prominent.” Southern Club member C. J. Prentiss declared that it should be moved away from the “factories, dump heaps, and negro cabins” near Greenlawn. Reflecting the attitudes of the Southern Club’s members and of other whites of the time, Prentiss took issue with placing the monument near a center of African American life and culture and in an area that was becoming increasingly industrialized. The area had become increasingly industrialized, but, in reality, the Black neighborhoods of the time were blocks away.

, the city’s oldest park, bounded by West, New York, and Blackford streets, and , which became part of the Plaza, were considered as alternate sites. Prentiss pressed for the monument’s relocation to because of its location outside the .

In 1919, State Senator Harry Elliott Negley sponsored a bill in the Indiana General Assembly on the club’s behalf to sanction a new location for the monument. It passed without dissent, and the City of Indianapolis provided the club with a small piece of land on the southern edge of Garfield Park. However, the Southern Club still needed approval from the federal government to move the monument, and a nearly 10-year-long effort to attain that permission ensued.

Finally, in 1928, Indiana Republican congressman Ralph E. Updike, a former Indianapolis judge who was the -supported candidate for the Indianapolis congressional district, introduced a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives to move the monument to Garfield Park. The obelisk was relocated to the park after the bill’s passage in April 1928. The Southern Club of Indianapolis secured Georgia congressman Malcolm C. Tarver, a Democrat, to speak at the rededication ceremony for the monument to the Confederacy on May 25, 1929. In 1933, the remains of the Confederate soldiers were reinterred in a mass grave located in Crown Hill Cemetery and marked by a new 6-foot-tall granite monument.

During the next 60 years, the Garfield Park Confederate monument received little attention. In 1990, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Indiana Republican U.S. senators and Dan Coates, Democratic congressman , and some local veterans groups and local historians supported a movement to reunite the monument with the Confederate graves at Crown Hill. Many residents opposed the move, and it remained in the park. In 2014, the Sons of Confederate Veterans called attention to the deterioration of the monument, asking for its restoration. Local government officials responded by saying that there were other city budget priorities. The group initiated its own fundraising campaign to repair the monument but failed to meet its goals.

Calls to remove the Confederate obelisk from Garfield Park peaked in 2017. That year, on August 19, Anthony Ventura vandalized the statue with a hammer in response to the civil unrest in Charlottesville, Virginia, which broke out in response to that city leaders’ proposal to remove Confederate iconography from its community parks.

Despite growing sentiment for the removal of the Garfield Park monument, it remained until 2020 when local protests erupted following the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota.

In June, Mayor Joe Hogsett ordered the removal and dismantlement of the Confederate monument from Garfield Park.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.