Photo info ...

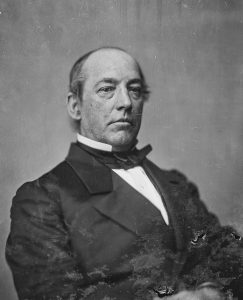

Credit: Mathew Benjamin Brady, Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsView Source

(Apr. 16, 1808-Jan. 7, 1864). Caleb Blood Smith was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of a merchant who moved his family to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1814. Named after a Baptist pastor of Massachusetts, Smith received an education in local schools and in 1823 enrolled in Cincinnati College, which shut down in 1825. He attended Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, but left school in 1827. That fall he relocated to Connersville, Indiana, to read law with Oliver H. Smith (no relation), who served as a Whig in the Indiana House of Representatives and later in the United States Senate.

Smith was admitted to the Indiana bar in October 1828 and quickly became a successful attorney. In 1831, he married the daughter of a local merchant. He purchased an interest in a local Connersville newspaper in 1832 and wrote editorials in support of the presidential candidacy of Whig Party leader Henry Clay against Democrat Andrew Jackson. A fluent orator with a fine voice, in the following year he won election to the Indiana House of Representatives, serving four consecutive terms, also serving as speaker of that chamber for one term. During that period, he supported Clay’s “American System” of government-funded internal improvements.

In 1841, he ran for and lost the election to the United States House of Representatives, the result of the strongly Whig district being divided by an independent Whig candidacy. In 1843, he ran again in a redrawn congressional district and won handily. He won reelection in 1845 and 1847.

In Congressional debates, he employed his oratorical skills to attack the majority. He opposed the annexation of Texas and during the (1846-1848) Smith followed the Whig party’s position of opposition to the war. Both issues were proxies for the question of slavery. In orthodox Whig fashion, he opposed slavery and its extension into new territories, but he also opposed the abolition of slavery. He sanctioned its existence in states where it was already established in law.

In 1848, when Whigs won a slim majority in the House, Smith received the chairmanship of the House Committee on Territories. However, he decided not to run for reelection in the following year after running afoul of growing antislavery, Free Soil strength in his eastern Indiana district. Before he retired from the House, he failed to secure a Cabinet post in the administration of President Zachary Taylor. As a consolation, he received a two-year appointment (1849-1851) on a commission to settle Mexican-American War claims and remained in Washington.

At the end of his appointment, Smith moved to Cincinnati to practice law and dive into the booming railroad-building industry. In 1854, he became president of the Indiana division of the Cincinnati and Chicago Railroad, which was building a section of tracks from Cincinnati to New Castle.

While never out of politics, during this time his Whig Party activities were muted. Sectional passions over slavery in Kansas territory and the brutal assault on Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts by Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina in the Senate chamber propelled him into the new Republican Party of Ohio, which was unequivocally antislavery in its ideological orientation.

Known as a stellar orator, Smith stumped for Republican candidates in the elections of 1856. The economic panic of 1857 hurt him and his railroad enterprise badly, wiping him out financially. In 1859, he relocated to Indianapolis to practice law. He quickly resumed a leading role in Indiana politics and was selected to be the chairman of the Indiana delegation to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1860.

As chairman of the state delegation, Smith was charged with preserving party unity behind an electable presidential candidate. As a coalition of former Whigs, antislavery Democrats, and “Know-Nothing” nativists, Smith sought to rally the Indiana delegation around Abraham Lincoln as the most electable candidate. Indiana’s early and unanimous commitment to Lincoln had a powerful influence on the convention and drove other state delegations behind Lincoln, who prevailed. Lincoln went on to win the four-way presidential election.

President-elect Lincoln, who had served with Smith in Congress and shared with him a veneration of Henry Clay, subsequently named him to head the Department of the Interior. As Interior had the largest government payroll in Washington, Smith’s patronage influence was significant. Lincoln allowed his Cabinet leaders free rein in the management of their departments. But, according to his biographer, the secretary had little skill in or liking for administrative duties. Along with his departmental duties, Lincoln tasked Smith with special efforts to suppress the slave trade and colonize formerly enslaved persons in South America. The secretary did not exert influence in Cabinet deliberations and feuded badly with Secretary of War Simon Cameron.

Less than a year into his service, he mulled over resignation and angled unsuccessfully for a Supreme Court appointment. Lincoln’s private announcement to the Cabinet in August 1862 that he planned to issue an Emancipation Proclamation to free enslaved people in the Confederate states dismayed Smith, the former Whig. He offered his resignation in November and asked the president to be nominated to the federal district court bench in Indiana instead. He took up the judgeship in December. Smith’s short tenure on the federal bench in Indianapolis was punctuated by bouts of ill health.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.