Indianapolis has a long history of producing crops and livestock and continues to be one of Indiana’s largest agricultural contributors.

Early History, 1820s-1850s

Agriculture was necessary for the survival of the city’s first settlers. Early residents raised livestock, especially hogs; cultivated fruit trees such as apples, pears, and quince; and grew a variety of crops including corn, sweet potatoes, and Irish potatoes. By the mid-1820s, residents harvested ginseng from the local woods and exported the dried roots.

During the 1830s, several grist and flour mills were established in the city including the overly ambitious . Indianapolis’ first brewery and the first tobacco factory opened in 1835, the same year that pork-packing appeared in the city.

Meat processing was not very successful until the early 1840s when John H. Wright began a profitable pork-packing business. When the came to town in 1847, the city found increased markets for its agricultural surplus. During the ensuing decade, agriculture continued to flourish and agriculture-related industries became an important part of the local economy with pork-packing, flour milling, and the manufacture of agricultural implements proving to be profitable ventures.

Agriculture and Agribusiness at the Forefront, 1860s-1910s

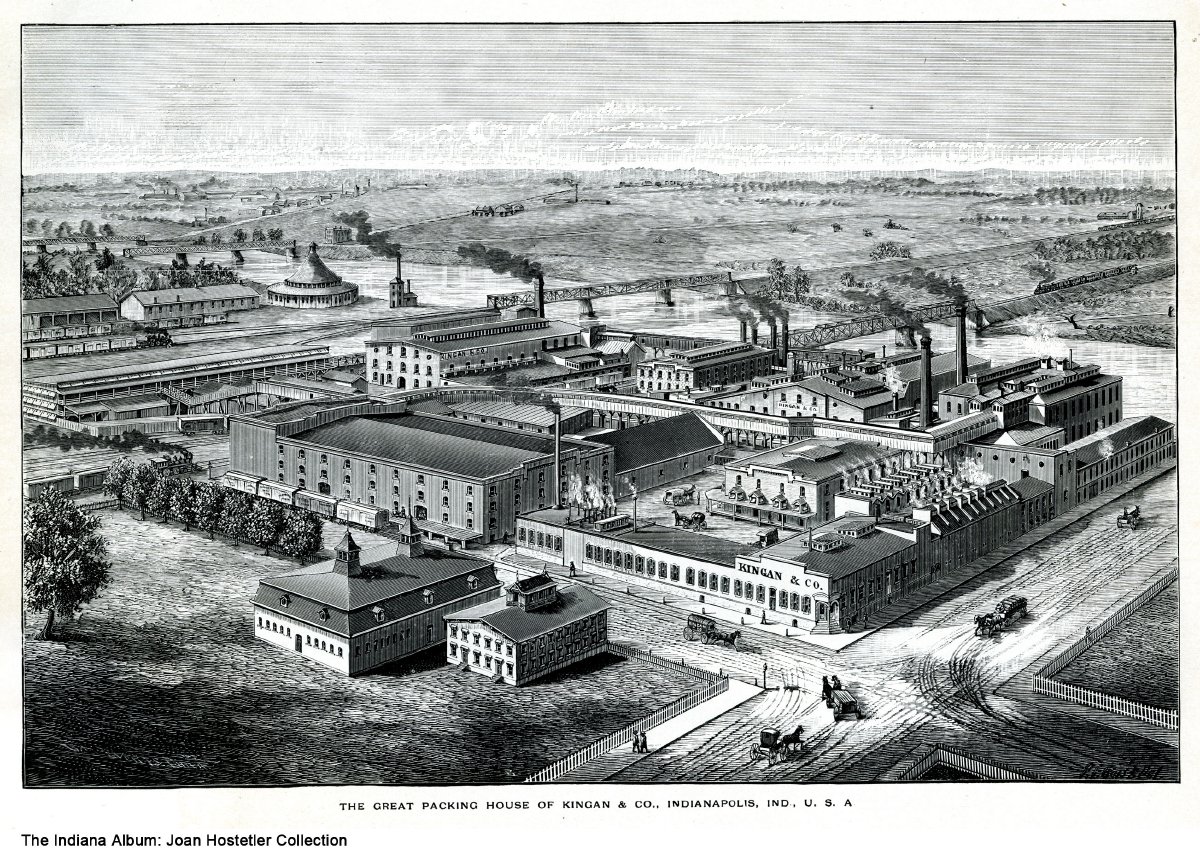

, a Belfast, Ireland firm that was one of the world’s largest meat-packing houses in its day, opened in the city during the Civil War era. By the mid-1870s, it employed hundreds of people. Other agricultural businesses followed. W. F. Piel & Co. began starch-making operations in the 1860s, and within a decade, the firm employed 80 people who used 500 bushels of corn a day in its factory. During the 1870s, Gilbert Van Camp and James Polk each pioneered the operation of small-scale canning in the Indianapolis area.

The 1870 U.S. Census of Manufacturers showed a highly diversified city economy with agricultural-related industries at the forefront. These included grist and flour mills, a woolen factory, soap factories, tanneries, breweries, tobacco manufacturers (including chewing, smoking, and plug tobacco as well as cigars), meatpackers, a broom manufacturer, a plow factory, a starch factory, several bakeries, and fertilizer companies. The Union Stockyards did well in this environment when it opened in the late 1870s.

By 1880, Indianapolis was the third-largest pork-packing city in the world, behind nearby Chicago and Cincinnati. During this decade, cigar manufacturing became big business in the capital with 87 cigar makers in town by 1884. Nine flour mills operated, and important bakeries in town included Parrott, Bryce’s, and the Indianapolis Cracker Company. Also during this decade, James T. Polk opened a dairy business, later incorporated as the Polk Sanitary Milk Company, and the was formed by the merger of three city breweries.

Indianapolis supplied 65 percent of the nation’s starch market in 1890 through the National Starch Manufacturing Company (a merger of Piel’s starch factory with several other firms). The Indianapolis were processing over a million cattle, pigs, and sheep each year by the early 1890s. Agriculture-related firms continued to be significant to the city’s economy in 1900, with meatpacking and flour milling recognized as leading industries. The state’s largest bakery, the , was organized in Indianapolis in 1905.

During the next two decades, meatpacking continued to grow. By 1919, the value of products in this industry approached $105 million. Related products such as lard, glue, soap, tallow, fertilizers, and hides continued to be produced in the city. By 1920, the Indianapolis Stockyards received almost 600,000 cows, 3,000,000 pigs, and 136,000 sheep annually.sSus

Sustained Importance and the Beginning of Decline, 1930s-1960s

In the 1930s, the production of livestock, poultry, and dairy products remained an important part of the local economy. Marion County boasted 20 commercial dairies in addition to six commercial orchards. Principal agricultural crops of the decade included corn, wheat, hay, oats, Irish potatoes, peas, and tomatoes, with the latter two crops grown primarily for canning.

The 1939 U.S. Census of Agriculture reported that 169,045 acres of Marion County were farmland (66 percent). The 3,336 farms in the county averaged about 55 acres. Agriculture-related firms in Indianapolis during the decade included (flour), the (canned goods), National Starch (starch), Stokely Bros. (canned goods), several meatpackers (including Armour, F. Hilgemeier Indiana Provision Co., Kingan, and Swift), two fertilizer manufacturers (E. Rauh & Sons Fertilizer Co. and Smith Agricultural Chemical Company), multiple breweries, a dozen bakeries, and over 15 dairy and ice cream companies.

Small family farms disappeared as the city expanded rapidly following World War II, resulting in a declining percentage of farmland in Marion County. The 1954 U.S. Census of Agriculture revealed that farmland accounted for just 52 percent of Marion County land use, although remaining farms were now larger in size, averaging 75 acres. By 1964, the census reported Marion County had 767 farms, averaging 120 acres. Farmland occupied 91,853 acres or 36 percent of the county’s land. Just five years later, another 3 percent of the county’s farmland was gone, along with 72 farms.

Loss of Farmland, 1970s-1990s

Following the 1970 consolidation of Indianapolis and Marion County through , the Department of Agriculture in 1974 declared Indianapolis to be the “biggest farm town in the United States” with a total of 602 farms occupying 29 percent of the county’s acreage. Most of the city’s farmland remained on the southside, producing crops such as corn and soybeans, and, to a much lesser extent, wheat, hay, and vegetables. Farmers continued raising cattle, but the number of pigs and chickens in the county had declined dramatically from previous levels. Small family farms were increasingly rare. Farms averaged 123 acres and served as specialized farms, raising one or two crops or producing one variety of livestock.

During the 1980s, farmland continued to disappear as new housing, shopping centers, and office parks sprang up around the outskirts of the city. Census figures recorded a declining number of farms in Marion County: 430 in 1978, 400 in 1982, and 361 in 1987. The average farm size grew during this time from 136 to 157 acres. With farmland accounting for 22 percent of the city’s acreage in 1987, important crops included soybeans, corn, wheat, and oats.

A 1993 estimate of 45,000 acres of county farmland put Indianapolis at less than 18 percent of its land devoted to agriculture, with continuing to be the most rural area of the county. Corn and soybeans were principal crops with several nurseries and greenhouses adding to the city’s agricultural production. Important agriculture-related industries in the city as of the early 1990s include AcmeEvans (flour), Continental Baking Co. (bread and cakes), Hebrew National Kosher Foods (meat processing), the Indiana Farm Bureau Co-op (feed and fertilizers), Maplehurst Farms (dairy products), and (starch).

The Continuing Significance of Agribusiness, 1998-

In 1998, moved its headquarters to Indianapolis. The organization regularly holds its national conventions here. The city remains home to Acme-Evans/ADM Milling, which operates the third-largest flour mill in the U.S. in Beech Grove. , first established as a division of in 1954, has become a global company that provides products and services to support livestock production and to improve animal health. , a successor to DowElanco (a joint venture of Lilly and Dow Chemical Company formed in 1989), focuses its business on agricultural chemicals, seeds, and plant biotechnology; and just north of Indianapolis in Hamilton County, Beck’s is the largest family-owned, retail seed company in the United States.

In 2012, the recognized the continuing importance of agribusiness and agbioscience to the local and state economy. Headquartered in Indianapolis, CICP created under its umbrella to ensure the prosperity and growth of this sector of the economy in the area.

Despite this, the downward trend of agricultural land continued the first decades of the 21st century. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of farms decreased by 17 percent, and the majority of farms had under 50 acres, with just 6 farms being on 1,000 plus acres. County farmland decreased by 13 percent to 17,371 acres, 78 percent of which was dedicated to growing soybeans and corn.

Agricultural Fragments, 2000-

Even with the loss in agricultural acreage, Indianapolis still has fragments from the city’s agricultural past in every corner in the form of old farmhouses, occasional barns, and the remnants of orchards. Fields of corn and soybeans are the most common agricultural fragments on the fringes of the city. Within more populated segments of the city, original farmhouses are surrounded by newer houses built when the farmer sold off his land. Growing Places Indy operates five micro-farms in the Indianapolis area, including one at , and around 100 urban farms and community gardens operated in Indianapolis in 2015.

In the densely populated areas near the city’s northern boundary, corn and soybean fields are interspersed with stylish housing developments, condominiums, and strip malls. In Pike Township to the northwest, suburban residential areas rapidly expanded. There are many large horse farms in the rolling hills, particularly near . Lynnwood Farm, a 623-acre property north of Indianapolis, became home to Northview Church, Plum Creek golf course, and surrounding neighborhoods. Its two-story corn crib, one of the last vestiges of the property’s time as a farm, was designated as a single-site conservation district in 2019 and was restored into a community space.

The southern boundary of Indianapolis is similar. The southside of Indianapolis is dotted with small truck farms and large greenhouses intermingled with corn and soybean fields. Many are still owned by families whose forebears came to the city in the mid-1800s. The southwestern corner of the city is characterized by many farms and small, regularly spaced farming communities like Valley Mills, , Maple Ridge, and . The most rural segment of the city, southeastern Franklin Township, still has active farms, some dominated by 19th-century farmhouses. Dairy farms, grazing cattle and horses, and large cornfields can be seen along Thompson and Southport roads. and other small communities in Perry Township fan out toward into land that was previously totally agricultural.

Marion County is still one of the state’s largest total agricultural GDP contributors, having an impact of $1.4 billion in 2012, with most of this sum coming from modern agribusiness. It is also the top provider of agricultural-related jobs in the state, coming in at an estimated 10,250 jobs in 2012.

FURTHER READING

- Bein, Rick. “Urban Farming in Indianapolis.” Traveling Farmer, Indiana University Pressbooks, https://iu.pressbooks.pub/travelingfarmer/chapter/1639/.

- Indiana Business Research Center, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. “Agriculture in Indiana Counties: Exploring the Industry’s Impact at the Local Level.” 2015, https://www.ibrc.indiana.edu/studies/AgReportOct2015_FINAL.pdf.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Markisohn, D. B. & Fischer, J. E. (2021). Agriculture and Agribusiness. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 11, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/agriculture-and-agribusiness/.

MLA:

Markisohn, Deborah B. and Jessica Erin Fischer. “Agriculture and Agribusiness.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/agriculture-and-agribusiness/. Accessed 11 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Markisohn, Deborah B. and Jessica Erin Fischer. “Agriculture and Agribusiness.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Mar 11, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/agriculture-and-agribusiness/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.