The United Northwest Area (UNWA) is located in what was once a large, unincorporated area known as . It is bounded by 38th, Meridian, and 16th streets as well as the . The western boundary of the neighborhood is irregular. Between 16th and 22nd streets, Fall Creek forms its border; between 22nd and 30th streets, I-65 is its boundary; and between 30th and 38th streets, Meridian Streets is its boundary. is located at its center. It includes three historically distinct neighborhoods: to the south, in the center, and to the north.

1830s-1900

With the opening of the in 1839, Nathaniel West established a cotton mill where crossed it. A small settlement called Cottontown grew up around the mill. Crown Hill Cemetery incorporated in 1863, and a street railway was extended to reach the new burial site. The Central Canal and the , which had its western terminus in North Indianapolis, attracted industry. In 1873, the Udell Ladder Works, North Indianapolis Wagon Works, and Henry Ocow Manufacturing Company all moved to the vicinity. That same year the area was platted up to 31st Street as North Indianapolis by several men whose names now appear as street names in the United Northwest neighborhood (Rader, Roache, and Udell). Residents sought annexation by the City of Indianapolis, in part, to get better rates for natural gas. They succeeded in 1895.

Two churches were established before 1900: Barnes United Methodist in 1879 and First Baptist North Indianapolis in 1885. The area also became the home of the Indianapolis Country Club. Founded in 1895 and located at the corner of Michigan Street and Maple Road (38th Street), the Indianapolis Country Club had a clubhouse, tennis courts, and a nine-hole golf course.

1900-1950s

Holy Angels Catholic Church arrived in the neighborhood in 1903 and opened a school in 1907. Riverside Methodist Episcopal Church completed its first building in 1906. Mount Paran Baptist Church was established that same year, and in 1908, founded Christ Temple Church on West Michigan Road. It moved to Fall Creek Parkway and Northwestern Avenue (Martin Luther King Jr. Street) in the mid-1920s and became the largest Pentecostal church in the neighborhood.

At the turn of the 20th century, local businessman David Parry, a manufacturer of carriages and automobiles, acquired several acres on the northwest edge of the neighborhood for his personal estate. Parry hired Scottish-born landscape architect George MacDougall to design the grounds, which Parry named Golden Hill.

Following Parry’s death, his family subdivided the land, and the neighborhood became an exclusive northside Indianapolis residential area. Golden Hill set a pattern that became typical in the UNWA. Around its perimeters concentrations of wealth appeared, while modest and substandard housing tended to be the norm at its core. Most of the neighborhood’s commercial development occurred along the Clifton Street electric railway line.

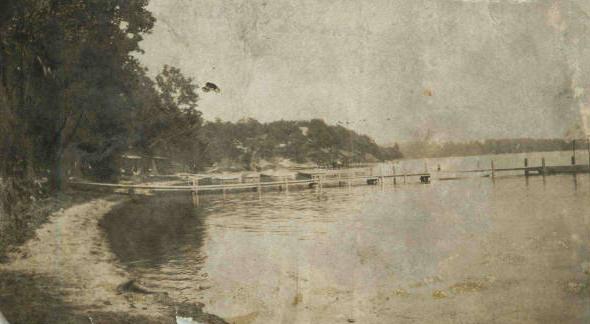

Until 1900, the area remained relatively undeveloped. In 1893, Mayor purchased 900 acres of land along the White River for development as a city park. It became a keystone to renowned landscape architect George E. Kessler’s 1909plan. Nearby, opened in 1903 on a triangle of land north of 30th Street along the White River.

The greatest period of residential growth in the area corresponded with the establishment of these attractions and the execution of parts of Kessler’s plan. Between 1910 and 1920, farms were gradually broken up into small plats. Over 75 percent of the area’s housing stock was built before 1939. St. Vincent Hospital, constructed in 1913, was another important institution that came to the neighborhood during this time. Bush Stadium, home of the Triple-A baseball team, opened in the southwest corner of the neighborhood in 1930.

During the first half of the 20th century, the UNWA was largely white and middle class, with a Black population at its center. The two groups remained largely segregated, with the exception of Christ Temple Church described in 1948 as “the only interracial Protestant congregation in Indianapolis.” Its membership at the time was about 60 percent Black membership and 40 percent white. Riverside Park only admitted whites, offering special days for African Americans to attend. Indianapolis Public School No. 87 was established for Black children in the neighborhood in 1937. , which had begun in 1898 as a settlement house serving African Americans at 802-814 N. West Street, moved to West 16th Street by 1944. It housed a cannery, workshop, and health care center.

1960s-2000

During the 1950s and 1960s, the UNWA transformed from “a racially balanced but segregated neighborhood” into one that was almost exclusively African American. The white population decreased by 59 percent, and the African American population increased by 119 percent.

The construction of I-65/1-70 brought significant change. The outer-belt-and-spoke-system of the new interstate would run through the northwest side neighborhoods. The state began claiming right-of-way and buying properties dislodging long-time residents in the UNWA. Reverend , assistant priest at Holy Angels Catholic Church, led neighborhood protests against the interstate but had little success. Construction of the I-65/I-70 inner loop was completed in 1975-1976.

During the 1960s, the neighborhood lost some 3,000 residents. This trend continued. The UNWA became an area filled with poor African Americans. As a result, the area also lost retail and entertainment businesses. Although Riverside Amusement Park abandoned its segregationist policies in the mid-1960s, it closed its doors in 1970. St. Vincent left its Fall Creek location for the far northside in 1974. It had been the area’s biggest employer throughout its history in the neighborhood. Along the border of the UNWA, one significant newcomer was the , which opened at the former estate in 1970.

The area’s religious institutions transformed with their population. Holy Angels was almost exclusively African American when Hardin was appointed its associate pastor. Riverside Methodist also had an African American minister in the early 1960s. Mt. Zion Baptist Church, an African American congregation, began worshipping at a new building at 3500 Graceland Avenue in 1960. Built at a cost of more than a million dollars and with the leadership of Rev. R. T. Andrews, Mt. Zion became the single largest and most active congregation in the area.

Along with charitable foundations and government organizations, Mt. Zion and the other churches worked hard to preserve some stability in the neighborhood. Mt. Zion, with contributions from , built apartment complexes for seniors and persons with disabilities, a daycare center, and a nursing home. Mt. Paran Baptist also maintained apartments for seniors. Pilgrim Baptist Church, which was established in 1939, provided counseling, job placement, a food pantry, and health care through its multi-service organization. Holy Angels’ school continued to operate, and Christ Temple Christian Academy opened in 1983.

The United Northwest Area Association was formed in 1967 by a group of concerned residents to address increasing poverty and crime, poor city and police services, and below-average reading ability among the area’s children. Participation in the Community Development Block Grant program since 1975 resulted in resurfaced streets, new curbs, and sidewalks, and over 150 houses rehabilitated. In 1978, United Northwest Area incorporated and added an economic development branch to its neighborhood association. Each of the three historic neighborhoods also maintained its own neighborhood organizations under its umbrella.

Flanner House remained in the neighborhood and opened a new building at 2424 Martin Luther King Jr. Street in 1979. The multi-service center administered federal and state welfare programs and offered adult education classes, vocational training, child-care programs, health care, and other services. The center also included a branch of the .

These efforts, though significant, did not translate into improvements in the neighborhood’s economic makeup. The 1990 census revealed an area that had high levels of poverty and crime. The Indianapolis responded by designating a large portion of the UNWA as “an area of special need.”

During the 1990s, many organizations in the area continued their work to improve neighborhood conditions. In 1990, Flanner House opened a new health center. operated the center, which was named for longtime director . The Indianapolis Public Schools built a new structure for School No. 42 in 1995, and Pilgrim Baptist Church undertook a major revitalization project to renovate School No. 41 for use as apartments. The church then also built a youth center and additional new apartment units. The land that had stood vacant since the closure of Riverside Amusement Park was redeveloped as the River’s Edge subdivision in 1999.

2000-present

At the beginning of the 21st century, a neighborhood survey revealed that over half of the properties in the African American UNWA contained buildings that were in some state of deterioration. A number of attempts have been made to revitalize the area. In 2003, in conjunction with the (INRC), the city’s Division of Planning, and Ball State University, the United Northwest Area, Inc. (UNAW, Inc.), and the United Northwest Area Association began work on a community master plan. The initial study, released in 2008, provided areas that presented opportunities for improvement including crime and safety; beautification; employment; education; jobs; housing; recreation; economic development; and family, health, and social services.

The Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street Corridor Enhancement Program was established in 2004 to develop a work program for improvements between 27th and 29th Streets. This initiative identified a grocery store, a hardware supply store, a bank, and a pharmacy as services that were needed to serve the area. In 2011, Bush Stadium redeveloped as Stadium Lofts, added new housing stock at the southern edge of the neighborhood in proximity to .

In 2014, the UNAW Inc. undertook creation of a Quality of Life (QoL) Plan to map out the UNWA’s assets and challenges and to apply measurable goals to improve the neighborhood. It found that many of the problems identified in 2008 remained the same and recommended economic development strategies similar to those outlined in the previous assessment. The UNWA continued to need much economic development, and it had become more of a food desert. Its last food market closed in August 2015.

The QoL Plan recommended strategies to reconstruct and activate abandoned commercial properties, to attract new businesses to the area, and to optimize use of Tax Increment Financing, a program that attracts businesses and helps to keep property taxes in the district for reinvestment in the community. In 2016, the “Northwest Area: Progress & Redevelopment Plan” outlined using an abandoned Carrier Bryant heating and air conditioning manufacturing facility as a catalyst for revitalization. It had been identified as a brownfield site by the Environmental Protection Agency, and federal funds could be used to clean it up and prepare it for future use.

Revitalization efforts also came through a “Riverside Regional Park Master Plan,” released in December 2017. Although Riverside Park was one of the oldest and second in size only to , it had not undergone any significant change or reconceptualization since its inception. With the plan, the City of Indianapolis acknowledged the need to create a master plan to enhance the quality of life of the neighborhoods surrounding it and to spark economic development there. The ambitious plan involves tying Riverside Park and the adjacent Kessler-designed Burdsal Parkway to Indianapolis Greenways, connecting the area to downtown and other parts of the city. Connecting the area to its waterways—the White River and Central Canal—are also part of plans being put into place.

In 2019, a brewery, Guggman Haus, was a significant addition to the Riverside area, and the opening of biotechnology complex on the southern edge of the neighborhood brought more commercial development to the vicinity. By 2020, new homes began to be constructed behind the brewery in the neighborhood with prices ranging from $100,000 to $300,000.

Is this your community?

Do you have photos or stories?

Contribute to this page by emailing us your suggestions.