Photo info ...

Credit: South Bend TribuneView Source

(Jan. 17, 1903-Nov. 6, 1987). Throughout her career, Indianapolis social reformer Roberta West Nicholson worked for equality. The Ohio native met her husband, Meredith Nicholson Jr. (the son of Indianapolis author ), in 1925 and moved to Indianapolis shortly thereafter. Nicholson had been brought up in a Republican family, but when she discovered that the heavily influenced the Indiana of the 1920s, she became an active Democrat.

Nicholson engaged in her first real reform work in 1932 when she helped establish the Indiana Birth Control League, later known as , reportedly at the behest of birth control activist Margaret Sanger. Thus began Nicholson’s long career as a family planning and social hygiene advocate. In 1943, she became the first director of the Indianapolis Social Hygiene Association, later the Social Health Association of Central Indiana (now ), a position she held until her retirement in 1960.

At the encouragement of her mother-in-law, Nicholson worked with the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Repeal. Appointed to the Liquor Control Advisory Board in 1933 by Indiana governor Paul V. McNutt, she was elected secretary to the Indiana convention that ratified the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition.

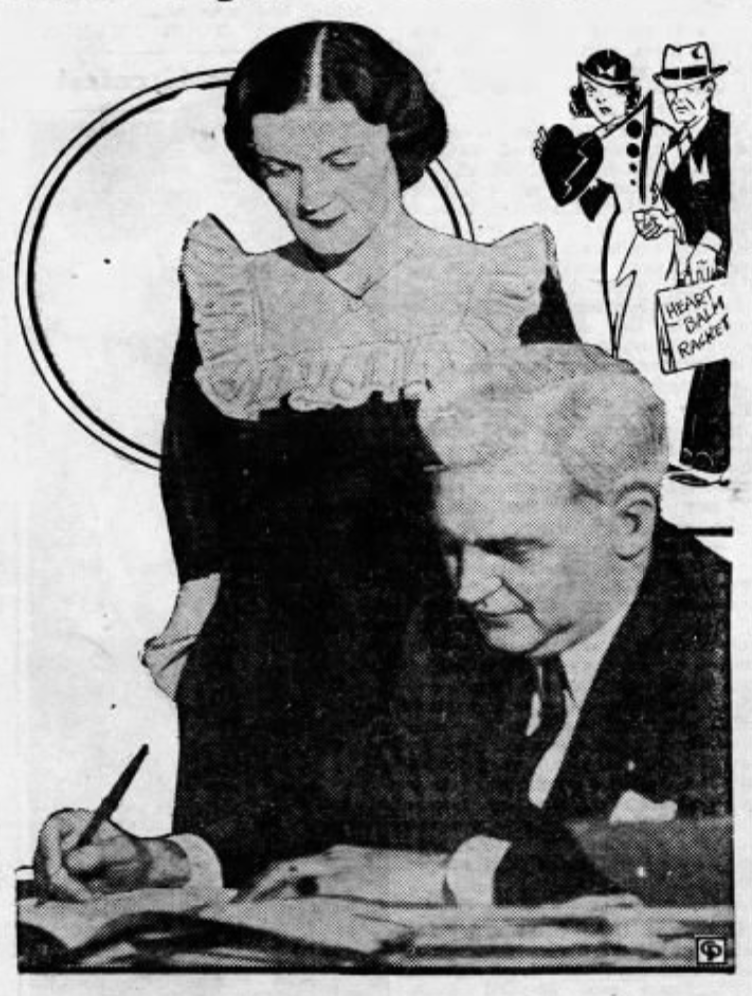

Her experience and qualifications made her a natural choice for public office, and in 1934 the county chairman convinced her to run for the state legislature. The only female representative in the 1935-1936 session, she made national headlines with her “Breach of Promise Bill,” also known as the “Anti-Heart Balm Bill” and “Gold Diggers Bill.” Nicholson’s proposed bill would outlaw partners, most of whom were women, from suing fiancés who broke their engagements or spouses who engaged in infidelity.

Nicholson felt that deriving monetary gain from emotional pain went against feminist principles. Her bill sought to increase women’s agency within the institution of marriage, which according to Nicholson had essentially been a “basic common law that the woman was chattel and that the man, in marrying her, was saying, ‘I buy you and agree to feed and clothe you’.” At a time of collective anxiety and changing gender roles, her bill, which the Indiana General Assembly enacted into law, engendered intense national debate about women’s equality and inspired similar legislation in at least 11 other states.

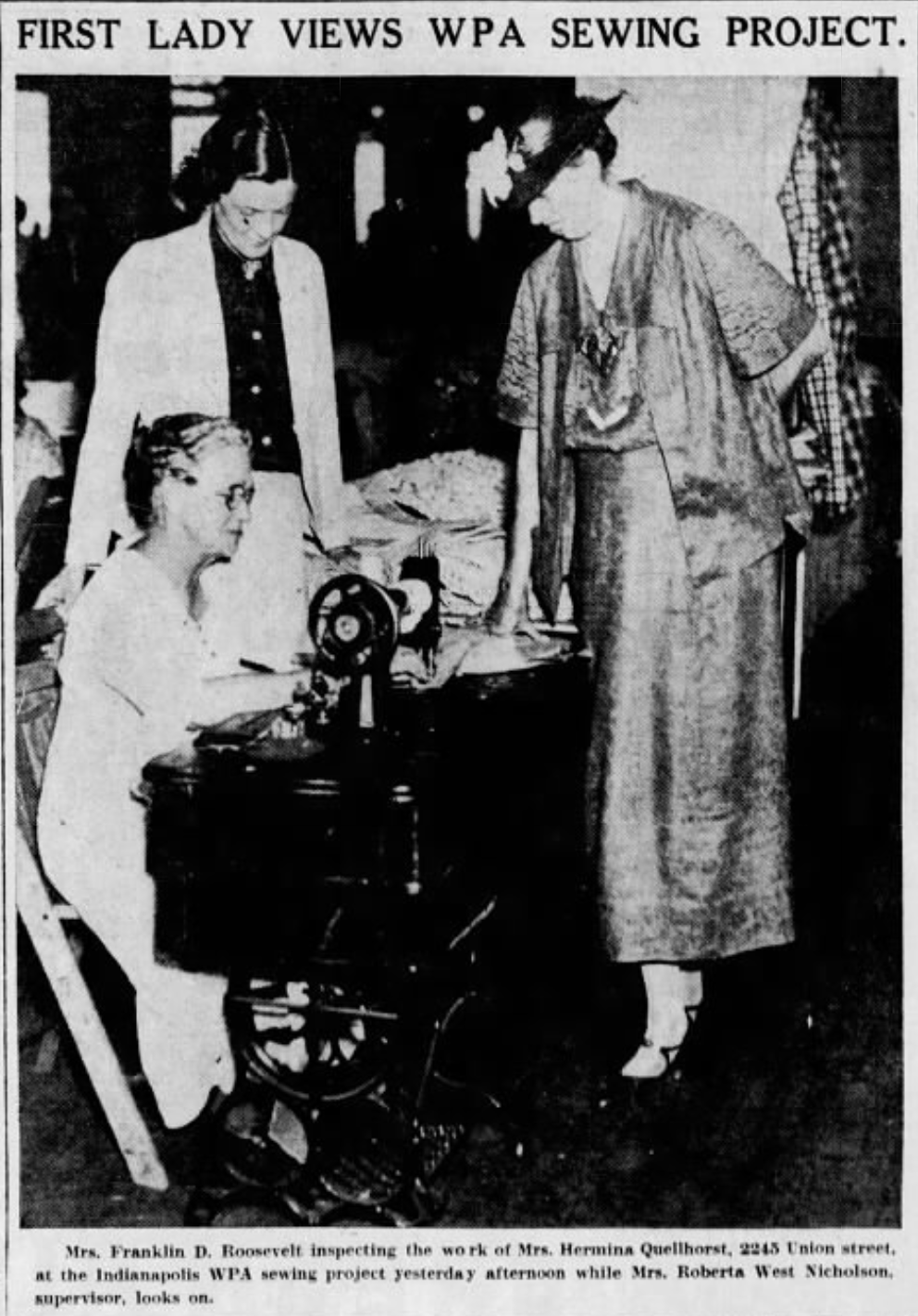

Once her term ended, Nicholson was appointed the Marion County Director of Women’s and Professional Work for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In her role with the WPA, Nicholson managed all jobs undertaken by women and professionals, which included bookbinding and sewing.

One of Nicholson’s largest tasks involved instructing WPA seamstresses to turn out thousands of garments for victims of the Ohio River Flood in 1937. The workers were headquartered at the , which is where flood victims were transported by the Red Cross during the disaster. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the seamstresses, and Nicholson felt that her approval of their work seemed to validate the WPA project.

Throughout the decades, Nicholson was active in numerous civic organizations and events, serving as a member of the , Council of Social Agencies, board of managers of the Indianapolis Orphans’ Home, , Parent-Teacher Association, Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Recreation, and state advisory committee on child welfare. She also served as state chairwoman for the New York World’s Fair, the President’s Birthday Ball, and a committee for aid to Chinese orphans.

While World War II lifted the country out of the Great Depression, it magnified discrimination against African Americans. After the passage of the Selective Service Act, the City of Indianapolis hoped to provide recreation for servicemen by creating the Indianapolis Servicemen’s Center, on which Nicholson served. While working at the center, she found businesses magnanimous in donating goods and services to white soldiers but mostly unwilling to do the same for Black soldiers. Outraged and determined, she finally located a facility for Black soldiers at , which was paid for by private funds. She then prodded and shamed businesses into providing support for the new facility.

One of Nicholson’s principal causes was the improvement of the system of . She was a founder and longtime member of the Juvenile Court Bi-Partisan Committee, an organization that worked within both political parties for the nomination of qualified candidates and of the Juvenile Court Advisory Committee, child welfare activists who met monthly with Juvenile Court judges to provide advice and support.

She also worked to uplift disadvantaged children with the , which placed children in foster homes and strove to meet their medical, social, and educational needs. She served on its board from 1935 until her death in 1987, the last 20 years as an honorary member.

In 1957, Nicholson received the Distinguished Public Service Award of the Indiana Public Health Association for outstanding achievement in the field of public health.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.