Natural Features

- Waterways

- Geology

Our Waterways

Fall Creek

58 miles | 318 sq. mi. watershed

Fall Creek originates near Honey Creek, Indiana and flows southwest to Marion County before joining the White River. Northeast of Indianapolis, it’s steep-walled valley was carved by glacier meltwater and dammed to create Geist Reservoir.

White River

362 miles | 2,271 sq. mi. watershed

The West Fork of the White River runs through Indianapolis before joining the East Fork and then the Wabash River in Illinois. The river existed before Wisconsin glaciers arrived 70,000 years ago and drained the southernmost reaches of the Laurentide Ice Sheet.

Pogue’s Run

11 miles | 13 sq. mi. watershed

This urban stream begins on Indianapolis’ east side, runs through a tunnel south of Downtown, and empties into the White River near Kentucky Avenue.

Flooding

This map shows areas with a one percent chance of flooding each year. Note the large extent of flooding possible along the White River north and south of Downtown, while levees and channeling would allow the White River and Fall Creek to stay within their bounds even during a 100-year flood event. Still, this map does not show the immense damage that would be caused by the failure of a levee or a reservoir dam.

From top: Parry Buggy Factory underwater during the 1913 flood, the Washington Street Bridge destroyed, and a flooded Riverside Park. Source: Indiana Historical Society.

Learn moreThe Great Flood of 1913

- 31.5 feetWhite River flood crest

- 7,000Homes destroyed

- 25Deaths reported

- $650 millionStatewide cost (2020 dollars)

The most disastrous flood in Indiana history swept the state in March 1913. Six inches of rainfall drenched Indianapolis over a five-day period that began Easter Sunday, March 23, 1913. As the White River crested, levees failed, sending torrents of water rushing through the city. Bridges were washed away, water supply was shut down for days, and transportation ceased.

Some areas in West Indianapolis were under 30 feet of water, and only the roofs of two-story houses were visible above the floodwaters. Thousands were left homeless, and a massive relief effort was organized at both the local and state levels.

In the decades after the flood, the city undertook a massive flood protection program, building levees, flood walls, and detention basins. They also dug deeper channels, straightened streams and rivers, and dug new channels to divert flood waters.

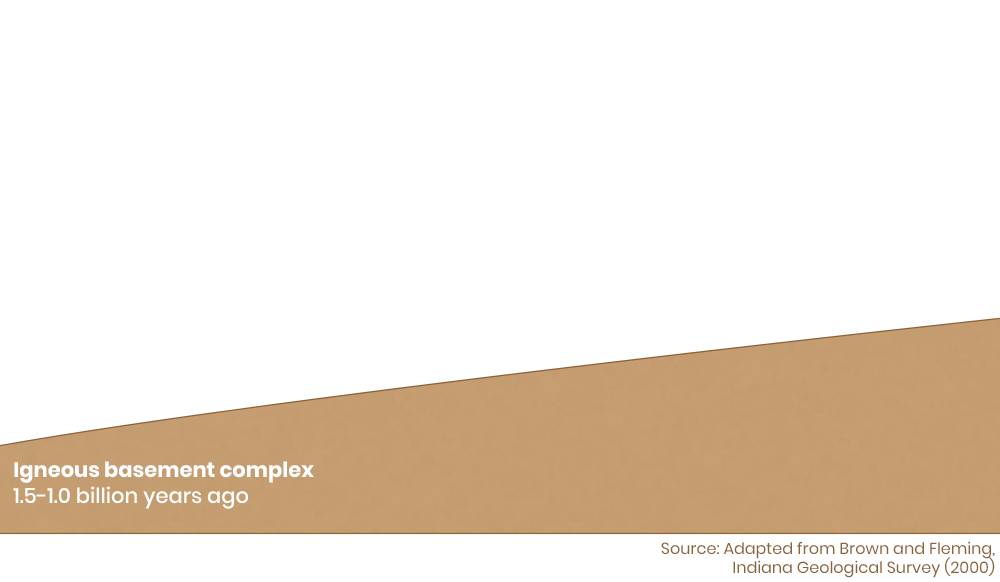

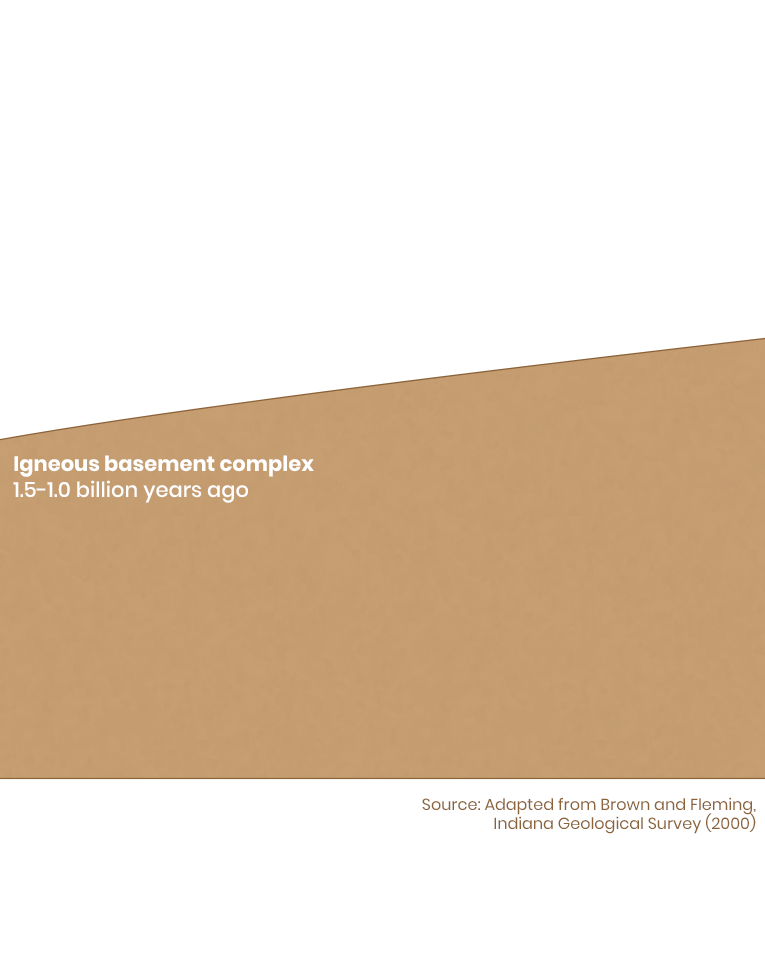

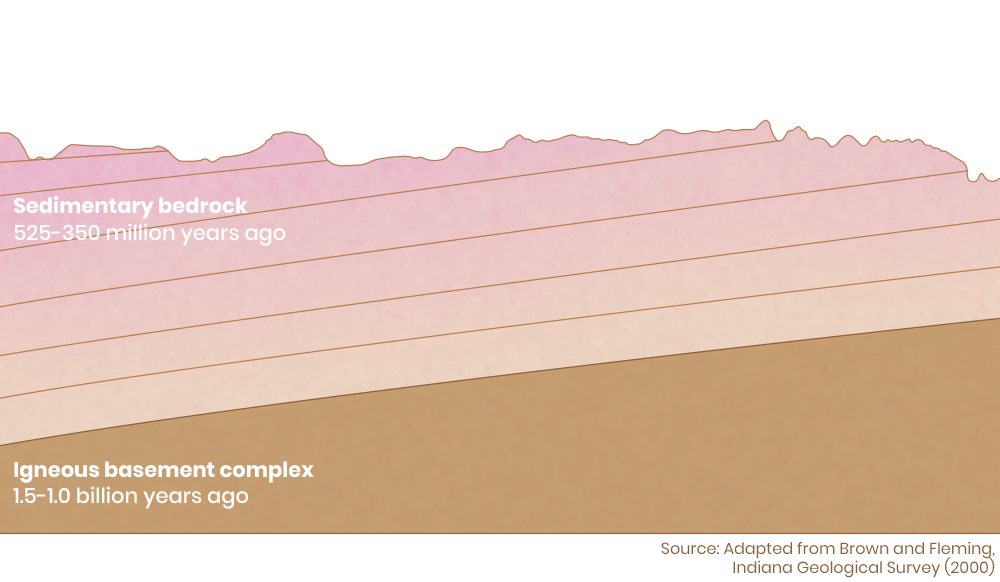

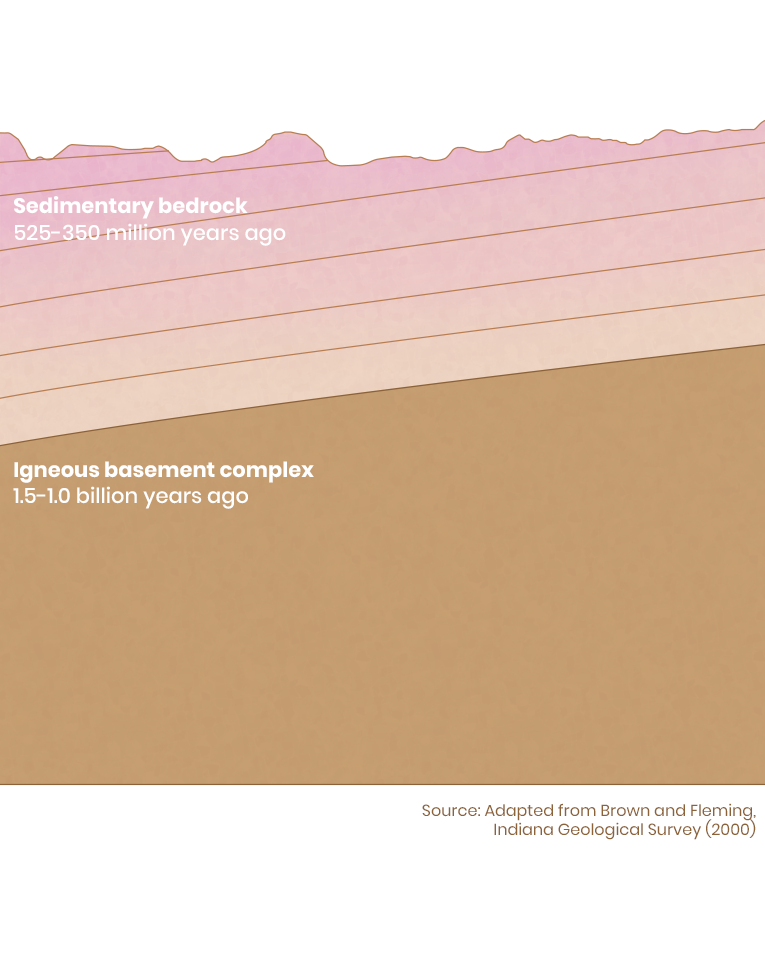

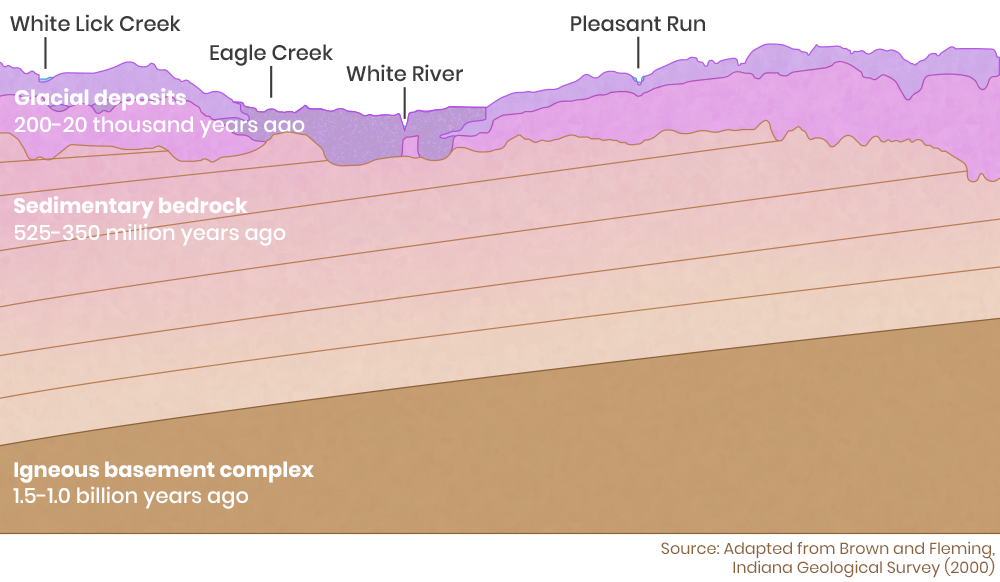

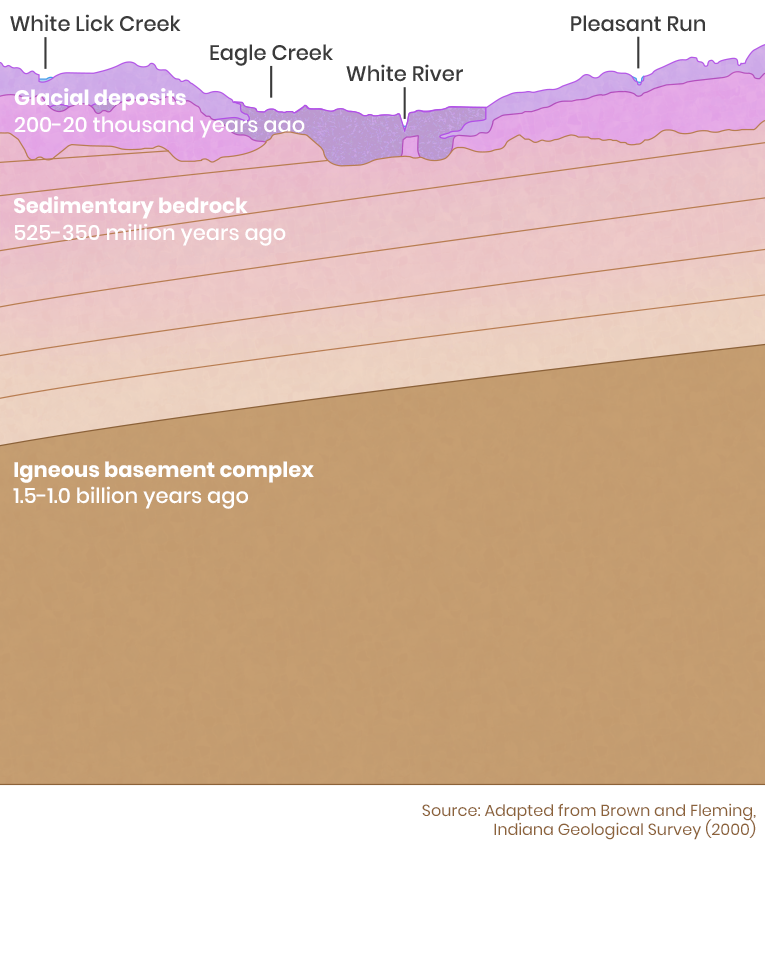

Geology

Our modern way of life, from the infrastructure that makes Indianapolis the Crossroads of America to the rich soils that power our strong agricultural sector, is built on millions of years of geological history. Here is that story.

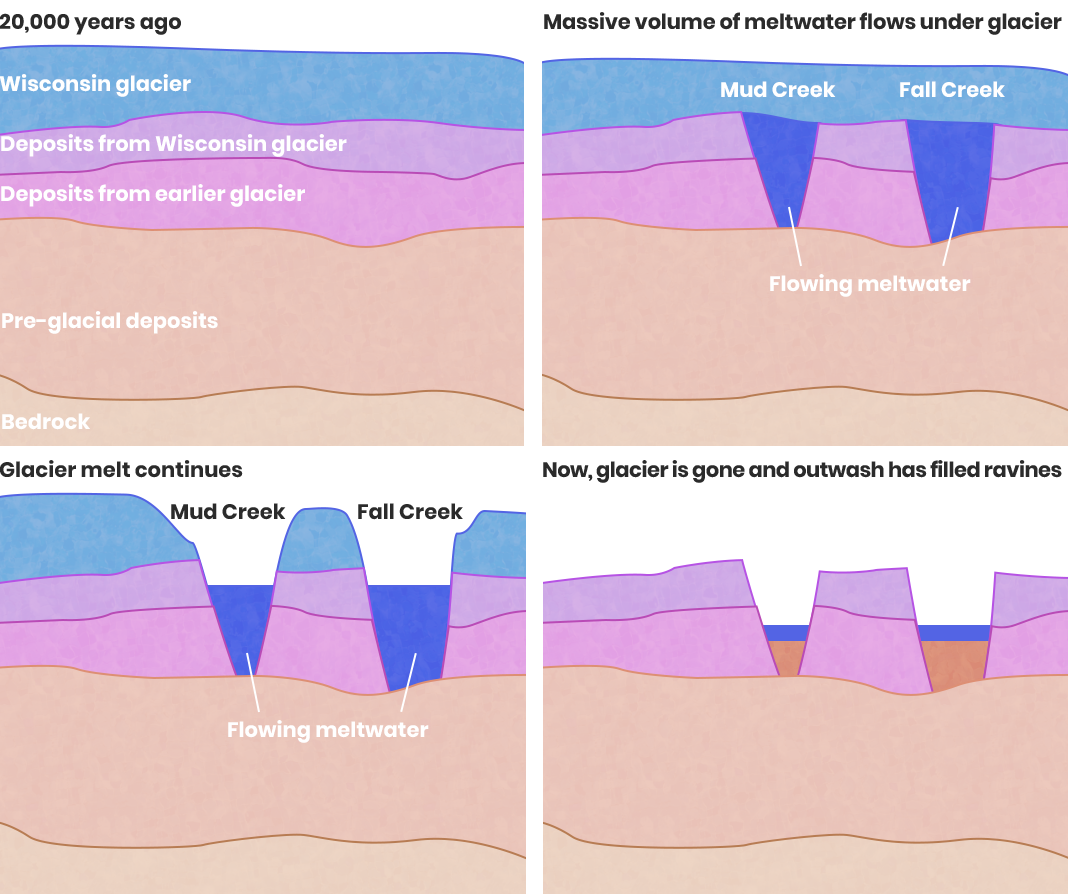

The Fall Creek Gorge that runs through Fort Benjamin Harrison State Park is the result of a glacial feature called a tunnel valley. It was formed entirely below the glacier that covered Marion County in the Ice Age. Melting water flowed out of the underside of the glacier, cutting a deep valley and washing away 150,000 years of glacial deposits. As the glacier melted, Fall Creek was eventually exposed to the air. Sediment from the melting glacier washed into Fall Creek, filling the valley floor and reducing the depth of the gorge.

Sources

Geology information was sourced from the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis and the Indiana Geological Survey. The floodplain map is provided by Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

Additional Information

Read these Encyclopedia of Indianapolis Entries for more information.

Other links: